As an engineering student in BITS Pilani, I was fascinated to watch statistics in action when our test scores were graded. The professors would pin the graph up on the notice board and the logic behind the grades was always transparently clear. The grading system in engineering schools is based on the principle that the marks scored by the students in any test will follow a bell curve.

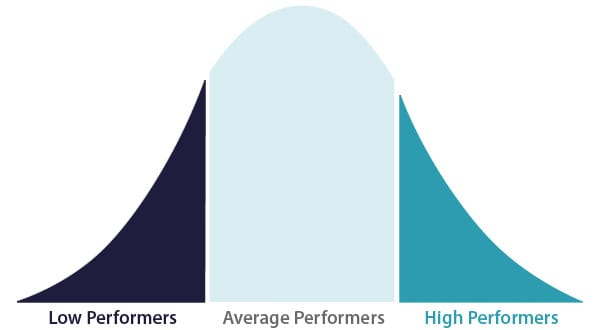

The mean score may be high or low depending on the difficulty of the test questions, but there will always be a standard deviation, with a small cluster of students with scores markedly higher than the mean and another cluster markedly lower than the mean. Most of the students fall in the cluster around the average, the C grade, with two small clusters on either side marking the B and D grades, and then the smallest clusters at the extreme sides of the bell, marking the A and F grades.

For the longest time, the world’s largest companies used the bell curve principle to assess their employees. Companies like Microsoft, Cisco, GE, believed that employees could be graded every year into average performers, high performers and low performers as a mathematical principle and it was just a matter of assessing who fell into which category. GE was especially famous for its policy of regularly culling the low performers in the belief that they were misfits in GE who would do better elsewhere.

By the early 2000s however, it had become obvious that the bell curve didn’t work too well as a corporate assessment tool. In an article titled Microsoft’s Lost Decade, published in Vanity Fair in 2012, author Kurt Eichenwald described how the bell curve had been responsible for killing innovation and fostering a political and bureaucratic culture in the company. The relative grading system meant that “the company’s superstars did everything they could to avoid working alongside other top developers, out of fear they would be hurt in the rankings. Microsoft employees worked hard to do a good job, but they also worked to ensure their colleagues did not.”

Microsoft finally ditched the bell curve a few years after the publication of the article. Bhaskar Pramanik, who was chairman of Microsoft India when it happened, recalls: “The initial reaction was ‘thank God!’ but that was followed by uncertainty, as people wondered how they would be measured. My generation of engineers had been using stack rankings since our early days. But what worked in the past did not work in the new work environment.”

In our last year in Pilani, we had a choice of taking three elective courses, unrelated to engineering, which were meant to broaden our outlook. I opted for Comparative Indian Literature, a course I enjoyed so much that I was the sole A grader in every test, all by myself at one end of the bell curve. Unlike the compulsory courses, where the numbers were in hundreds, there were only 12 of us enrolled in this course, and before long, I was approached by one of my classmates. Could I score low in the next test so I would not be the only A grader?

In a college exam, a student’s marks are entirely his own and the friend who helped him study gets no credit. “Today, a person needs to be appraised not just on individual impact, but on teamwork,” says Pramanik, who has retired from Microsoft India, but is active on several company Boards. “To succeed, you have to be smart, you have to be collaborative and you have to develop yourself based on feedback.”

Microsoft’s new appraisal system stresses feedback, with the appraiser and appraisee required to do at least four “connects” a year, where the discussion is around what was achieved in the last quarter, what can be achieved in the next quarter and what could have been done better. One of the issues discussed is how the appraisee has helped others, a crucial trait in the long run. Salary hikes are left to team managers, who are given a budget. The manager could possibly divide the budget equally among team members, but they know this would be a recipe for disaster in the long run. Managers know they must differentiate and ensure higher rewards for those who have greater impact, else they will be left with a low performing team.

Microsoft India and other companies have faced some challenges in implementing the new system. For one, Indian workplaces have never been big on feedback, with most employees seeing it as a confrontation. The old bell curve system also mandated feedback, but employees usually focused on their grades, seeing them as a reflection of the quantitative results they had achieved. They were not interested in the behavioural aspects relating to how the results were achieved. That is the most important cultural change we need in our workplaces,” says Bhaskar Pramanik.

Also Read: Chaos At Rajkot Airport After Pilot Refuses To Fly Plane To New Delhi