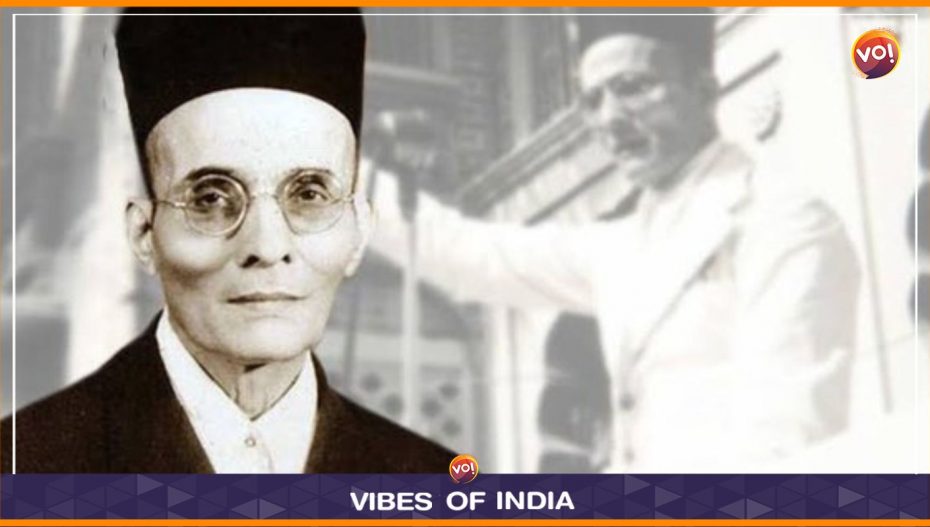

One of the most complex individuals in contemporary history is Vinayak Damodar Savarkar. Regrettably, the extremes of black and white do not do credit to Savarkar’s complex nature as a man, revolutionary, reformer, Hindutva ideologue, and accused in the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi when the discussion is polarised between them.

Savarkar’s strong hero complex, which borders on narcissism, and the intense and frequently contradictory aspects of his personality set him apart from his contemporaries.

While the opinions of Savarkar’s contemporaries like Mahatma Gandhi and B.R. Ambedkar evolved over time, they were always rooted in his childhood aspirations of a militarised, militant nation. His politics would continue to be shaped by these ossified instincts.

Savarkar founded the revolutionary organisation ‘Rashtrabhakta Samuha’ in November 1899. Savarkar and his allies desired complete Indian independence. Later, it was renamed “Abhinav Bharat” in commemoration of Guiseppe Mazzini’s “Young Italy” movement in Italy.

Mazzini had influence over Indian nationalists prior to the rise of Communism and the Russian Revolution, notably Savarkar, who penned his biography in 1907. Brahmins and non-Brahmins were both Savarkar’s associates.

Savarkar organised a sizable bonfire of imported clothing and other items with Lokmanya Tilak in attendance while a student at Fergusson College in Pune. This is reportedly the first bonfire of clothing created abroad.

Savarkar, 23, left his wife Yamuna (Mai) and their one-and-a-half-year-old son Prabhakar on June 9 and headed to England to pursue a law degree. Yet, he was a targeted man. The Bombay government wrote to Scotland Yard about him on June 14 of that year.

Savarkar was in London studying for the bar. Unlike to several of his Indian classmates, he was not persuaded by communism, fabian socialism, or the more extensive discussions about socio-economic injustice.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that he has strict beliefs and is egocentric. When someone later in life asked him if he had read Karl Marx, he reportedly responded immediately with the inquiry, “Had Marx read Savarkar?” Obviously, reports indicate that he had read about communism.

Savarkar wrote a book about the 1857 revolt that praised it as an instance of Hindu-Muslim harmony and refuted colonial propaganda that it was just a “sepoy” mutiny. Despite being prohibited in India until 1946, some people sneakily read the book.

The majority of Savarkar’s writings, including this book, focused on history. But most of them were rife with romantic and rhetorical embellishments rather than a scientific and objective explanation of the facts.

Savarkar was detained in London in 1910 for his revolutionary efforts, given two sentences of 25 years each, and transferred to the infamous Cellular Prison in the Andaman Islands. If he had survived the ordeal, he would have been freed from prison only in 1960 because these terms were to run consecutively.

Savarkar’s clemency appeals to the British was written from this notoriously severe prison. These letters were cited by Rahul Gandhi as an illustration of Savarkar’s surrender to the British.

A more nuanced perspective would judge Savarkar based on his later deeds rather than the strategies he employed to escape from prison, even though doing so may be accused of humanising Savarkar. In May 1921, Savarkar and his older brother Babarao were transferred to jails in the Bombay Presidency.

Savarkar was released in January 1924 with the stipulation that he would live in the Ratnagiri district, not leave its boundaries without permission from the authorities, and refrain from engaging in politics. Babarao was released unconditionally in September 1922.

The Savarkar who entered the Cellular jail was a different person than the one who left it after ten years. The new Savarkar was enraged with Muslims, whereas the old Savarkar supported Hindu-Muslim unity to free India from British rule.

This resentment is ascribed to Savarkar’s experience in the Andaman Islands and the fanaticism of the Muslim jail guards. The causes of this change of heart are still up for debate. Savarkar, however, did not use his hate of Islam as a ruse to gain favour with the British.

Savarkar, unlike Jinnah, believed that politics was personal and vice versa. Savarkar’s mentality still had wounds from the Andamans, despite the claims made in the writings of his fellow detainees that Muslim captives also had to endure the worst of these abuses.

His groundbreaking book, “Essentials of Hindutva,” which formed the philosophical groundwork for Hindutva as an ideology, was written at Ratnagiri in 1921. It stressed cultural nationalism over territorial nationalism and said that only Hindus should live in India—not Muslims or Christians!

In order to promote Hindu unity, Savarkar engaged in events like interfaith eating, allowing Dalits access to temples, and shuddhi. He did, however, still have some biases towards the upper class and was not a radical, anti-caste reformer like Phule or Ambedkar.

Although Savarkar’s detractors assert that he was the first to advance the two-nation theory, which ultimately resulted in the division of India, the concept had been advanced for more than three decades before he authored his book.

These include Sir Syed Ahmed Khan (1888), Lala Lajpatrai (1899 and 1924), poet Sir Allama Muhammed Iqbal, and Chaudhuri Rahmat Ali (1930s). Lajpat Rai criticised both Pan-Islamism and Hindu revivalism. The Punjab Hindu Sabha was founded in 1909, and the All India Hindu Mahasabha was established in 1915, all of which helped to widen the rift between Hindus and Muslims. The All-India Muslim League was founded in December 1906.

Finally, one of the factors leading to separation was Hindu fanaticism. The opposition of fanatical Hindus to partition did not make any sense, as Rammanohar Lohia argues in his book “Guilty Men of India’s Partition,” as Hindu fanaticism was one of the reasons that led to the division of this nation.

While it is asserted that Savarkar worked with the British and supported their divide-and-rule strategy, British government records, which provide a fascinating psychological profile of the man, show that Savarkar continued to “show a strong anti-Muhammadan bias and… (also) entertain feelings of disaffection against [the] government” while incarcerated in Ratnagiri.

Additionally, it was discovered that he had been “collecting irresponsible youths around himself to promote his revolutionary aims under the guise of Harijan upliftment work.”

Because of this anti-British sentiment, Savarkar’s restrictions persisted until the Bombay province’s short-lived Dhanjishah Cooper-Jamnadas Mehta ministry freed him in 1937. Muslims in Ratnagiri were treated by Hindus in a demeaning manner, much like untouchables. Nonetheless, Savarkar’s anti-caste campaign excluding Muslims is not mentioned.

Together with Muslims, Gandhi and the Congress were Savarkar’s other sworn enemies. Savarkar was past his prime and in his fifties when the restrictions were lifted. Gandhi had already cemented his place in politics by that point.

It was clear that Savarkar and Gandhi couldn’t cooperate. Gandhi’s goals of nonviolence, satyagraha, and Hindu-Muslim harmony were not in Savarkar’s favour. His disdain for these approaches is clear from his poetry “Gomantak.” His writings, such as the play “Sangeet Usshap,” also portray Muslims through their anti-heroes as proselytisers, villains, and sexual predators. More than the British or Muslims, Savarkar’s antipathy to Gandhi and the Congress influenced his politics.

The Hindu Mahasabha participated in coalition governments with the Muslim League in Bengal and Sindh, in contrast to the Congress, which attempted to keep the League at bay. After the Mahasabha’s humiliation in the 1945–46 elections, it became clear that Savarkar had a very little base of support, mostly among the higher castes of Marathi.

Savarkar had a strong hero complex and believed he was a natural-born leader. Savarkar’s ability to lead a democratic political party may have been constrained by his ongoing enjoyment of the leader’s role and his history of revolutionary activity.

Nathuram Godse assassinated Mahatma Gandhi in 1948, and Savarkar was detained as a co-accused. The court pronounced Savarkar not guilty and declared him free. Ultimately, Savarkar was charged in the Justice J.L. Kapur Commission of Investigation report from 1969, which stated: “All these facts taken together were destructive of any theory other than the conspiracy to murder by Savarkar and his group.”

This was based on comments made to the Bombay police by Savarkar’s secretary Gajanan Damle and bodyguard Appa Kasar. In contrast, the Supreme Court determined in 2018 that the commission’s conclusion was merely a “general observation” and had no bearing on the criminal court’s decision to acquit Savarkar.

In conclusion, who was Savarkar? A demagogue who widened the Hindu-Muslim split and aided the British, or a revolutionary?

A cold-hearted person who was unmoved by the passing of his young daughter Shalini, or a passionate, romantic poet who penned “Ne Majasi Ne” and “Jayostute”? Even when his patient wife Yamunabai was near death, he refused to visit her.

Savarkar’s chilly and callous treatment of his wife is vividly depicted in a short story written in Marathi by the author Vidyadhar Pundalik. Was Savarkar a social reformer or an apologist for the upper caste motivated more by a desire to stop the lower castes from being persuaded by Muslims and Christians than by a real desire for social reform?

Was he a freedom fighter or someone whose bigger politics and behaviour were dictated by his feelings of enmity towards Gandhi and the Congress? The truth might be found in the awkward middle ground, as it always is.

Also Read: Karnataka Elections: EC Announces Polls On May 10, Results On May 13