Krishnagiri (Tamil Nadu): A shiny new building stands on the national highway between Bangalore and Chennai, three kilometres from the town of Krishnagiri in northwestern Tamil Nadu.

Inaugurated just last year, this five-floored building — roughly 12 metres wide and 16 metres long; painted cream and white with orange highlights — could pass as a residential apartment but for two unusual features.

First, the parking space out in front is disproportionately large – almost three times the plinth area. Second, embossed atop it is the Bharatiya Janata Party’s trademark saffron and green lotus.

This is the BJP’s new party office in Tamil Nadu’s Krishnagiri district.

It is the result of an announcement made by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, back in August 2014, that the party should have offices in all states and districts, each “equipped with all the modern communication facilities”. The very next year, the BJP decided to build new offices in 635 of 694 districts in the country. By March 2023, that target had been hiked to 887 district party offices.

The logic was impeccable. As Arun Singh, a BJP general secretary, told the Economic Times in 2020, “Earlier…an MLA or local leader (would) make the office on his own premise [sic]. Because of this, several other leaders will not come to the office. Since the party has grown, it should have offices on its own with all facilities like library, conference hall and video and audio conferencing room.”

In March 2023, while physically inaugurating the Krishnagiri office — and nine others in Tamil Nadu through video conferencing — BJP national president J.P. Nadda told reporters that work on 290 district offices has been completed. Work was underway on the rest.

This construction spree by the BJP has not received the attention it deserves.

The BJP’s construction blitz

In terms of size, the party office in Krishnagiri is not an outlier.

Even in Odisha, as The Times Of India noted in 2016, the BJP’s new district offices have a construction area of around 10,000 square feet, abundant parking space and a conference hall with seating capacity for 250-300 people. Other district offices — whether in Manipur (like the recently burnt party office at Thoubal), Kerala (Kannur) or Himachal Pradesh (Una) — are large as well.

These 290-odd district offices are just the start. The BJP is also building party offices in bigger cities. Several of these are large, well-equipped and located on prime acreage as well.

In 2018, for instance, the party unveiled its new 170,000 square feet HQ in central Delhi’s Deen Dayal Upadhyay Marg, no more than a kilometre from the city’s Connaught Place shopping precinct. The carpet area of its earlier head office, in a Lutyens bungalow at 11, Ashoka Road and the adjoining bungalow at No. 9, scarcely compare to the grand new precincts. At the inauguration, party president Amit Shah said the new office was bigger than the office of any other political party in the world. Incidentally, the BJP is still using 11, Ashoka Road as the headquarters of its IT Cell and its election ‘war room’.

In 2021, to take another instance, it unveiled a new office for the Gurgaon BJP at the Signature Tower crossing on the Delhi-Jaipur Expressway. Describing the office, the Hindustan Times said it was “spread on an area of around 100,000 square feet… has (a) library, media room, IT room and separate enclosures for different party cells.” It also has two levels of basement parking; an auditorium where 600-700 people can be accommodated; two large conference rooms; and residential space for party workers and leaders visiting from other districts and states. Its cost is unknown.

Two years later, Modi inaugurated a residential-cum-auditorium complex built across the road from the BJP’s new headquarters. This will be used by the party’s general secretary/minister-level leaders and for big party meetings, the media reported.

New offices have also come up elsewhere in urban India – like Trivandrum and Thane. The party is also erecting new offices for the Delhi BJP – and for the Madhya Pradesh BJP.

The Delhi BJP’s office borrows, as the Economic Times reported in 2023, design elements from south Indian temple architecture. It is coming up on a 825 square metre plot in central Delhi; and has a built-up area of 30,000 square feet. “The building will have two basements for parking of 50 vehicles,” Delhi BJP treasurer Vishnu Mittal told the newspaper.

Its ground floor will have, as Mittal told the daily, a press conference room, reception and canteen. On the first floor, an auditorium with a sitting capacity of 300 people. On the second floor, offices of Delhi BJP’s cells and staff offices. On the third floor, offices of party vice presidents, general secretaries and secretaries. And, on the top floor, offices of Delhi BJP president and general secretary (organisation) besides rooms for Delhi MPs and in-charges of the state unit.

While the cost of all these buildings is unknown, another building coming up — the Madhya Pradesh BJP’s new office in Bhopal — is estimated to cost almost Rs 100 crore. Yet another party office — for the Assam BJP — built over one lakh square feet, with a guest house, a modern media centre, five meeting halls and a 350-seater auditorium — can accommodate 5,000 people and has been valued at Rs 25 crore.

In all, the full scale of this buildup is unknown. In the past, Nadda has pegged the targeted number of new party offices as high as 900. It’s not clear, however, how many of these are coming up in towns and cities.

Hardwired into this construction blitz is a larger question.

The tale of a curious paradox

As this article goes to press, the first two phases of the 2024 elections are over.

This time around, the polls feel more lacklustre than earlier. Reams have been written hypothesising the reasons — the absence of a strong opposition; an election officially sans issues; the long duration of the polls. Apart from these, there is also voter fatigue. Even before they could recover from the economic shocks of demonetisation and GST, Indians were hit hard by Covid — and the botched state response that followed. The outcome has been a skewed recovery that has seen the very rich gain while the rest of the country got mired in joblessness. This is a time when income inequality is at a 100 year high; and people are unable to save as before.

But even as Indians struggle, the economics of the BJP has seen a dramatic improvement. Not only is it outspending rivals in elections, it is also amassing real estate assets while maintaining healthy cash reserves – Rs 5,400 crore, by March 2023.

A question has gone unasked here.

The buildings are just a highly visible part of the party’s investments. It has also vastly outspent its political rivals in state and national polls — both in the 2019 polls and in the current elections. It has also been repeatedly accused of engineering defections in rival parties to retain power and it has been accused of benefiting from the government’s use of expensive high-tech spyware like Pegasus and newer variants to surveil opposition leaders and prominent citizens.

So how much money, exactly, does the BJP have?

This question has not received the attention it deserves despite it being widely known that India’s political parties present their financial reports to the Election Commission in a notoriously sanitised form. Parties don’t report their full income. Their most consequential expenditure — on the means through which they come to power — is not disclosed or severely under-reported as well.

In the case of the BJP, this is an especially strange miss. The party’s financials have escaped a closer look even though, as a Raipur-based political observer told The Wire, “The BJP’s electoral dominance comes out of its financial dominance.”

And yet, the country’s political commentariat, while penning op-eds and books on the BJP’s ability to keep winning, has not examined the party’s economics.

The costs of this wilful blindness run deep. Ten years after the BJP came to power, Indians have no idea how deep the party’s pockets are – nor how this financial reserve was built.

However, a look at two prominent heads of expenditure by the party – its construction spree, and its campaign expenditure – throws up some indicative numbers. And suggest its officially declared income of Rs 14,663 crore between 2014 and 2023 is likely a gross understatement.

1. What is BJP spending on its new buildings?

Tracking the party’s expenditure is one way to answer that question.

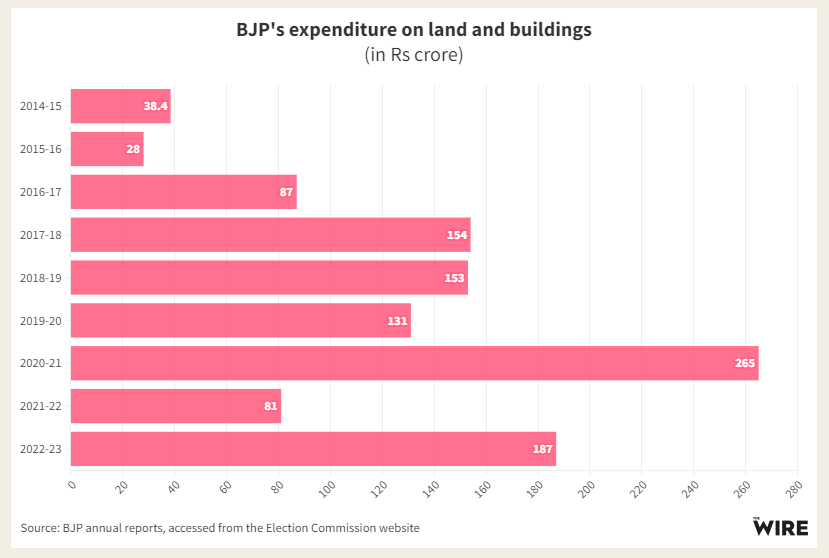

Let us start with buildings. Going by its annual reports between 2014-15 and 2022-23, the BJP has spent Rs 1,124 crore on land and buildings.

The Times of India was told in 2016 that each district office coming up in Odisha would cost between Rs 2 crore to Rs 3 crore — a total outlay of Rs 80 crore for 36 offices.

That was almost eight years ago. Given jumps in land rates and construction cost, more recent structures are likely to have cost more. The Krishnagiri office, for instance, stands on the Chennai-Bangalore highway, barely thirty minutes from the rapidly industrialising cluster of Hosur.

Land rates here, a local builder told The Wire, stand at Rs 5,000 per square foot — roughly Rs 5 crore for the plot.

Basic construction, he added, will cost Rs 1,500 per square foot. This can go up to Rs 3,000 per square foot. In all, he pegged the likely cost of construction at a minimum of Rs 1.5 crore. “A well-furnished building will cost close to Rs 3 crore,” he said.

In March 2023, Nadda said 290 party offices had been completed. Even assuming the cost of these buildings (spanning land and building) has remained flat over the last eight years at Rs 3 crore — the party’s outlay works out to Rs 870 crore on district offices alone. For all 887 district offices, the party’s planned outlay works out to Rs 2,661 crore.

The party is also building larger offices in bigger cities. As this article said above, its Guwahati office has cost Rs 25 crore and the Bhopal office is expected to cost Rs 100 crore. Assuming one large office per state and Union territory — at Rs 25 crore apiece — nets us another Rs 900 crore. That adds up to Rs 3,500 crore.

That number could be higher. District offices might cost more than Rs 3 crore. In Odisha, for instance, the market price of the land is said to be higher than that mentioned in the sale deed. The party might build more than one large office in each state. Also, as things stand, Congress leader Kamal Nath has alleged the BJP spent Rs 700 crore on its Delhi HQ alone.

The Wire has emailed Rajesh Agarwal, the BJP’s national treasurer, for details on the party’s construction plans and budgets. Questions were also emailed to Naresh Bansal, the party’s joint treasurer. Subsequently, both were informed about these emails on WhatsApp. This article will be updated when they respond.

2. How much is the BJP spending on election campaigning?

For the years between FY 2015-16 and FY 2022-23, the BJP’s annual reports peg electioneering costs (“Election/General Propaganda”) at a total of Rs 5,744 crore. However, independent studies, like the one from Centre For Media Studies (CMS), peg the party’s expenditure in the 2019 elections alone at “close to Rs 27,000 crore.” Anecdotal reports too peg the election expenditure of party candidates as much higher than the Election Commission’s cap of Rs 1 crore per constituency.

Another large question has gone unasked here. According to CMS, the BJP accounted for nearly 45 % of the total expenditure by political parties – Rs 60,000 crore — in the 2019 national polls. In 1998, the BJP’s share in total expenditure was much lower, at 20%. The 2024 hustings are projected to cost twice as much — Rs 135,000 crore.

If the party’s spending share stays the same as in 2019, it will end up spending Rs 60,750 crore. Which works out to a total expenditure of Rs 87,750 crore between these two Lok Sabha elections. On the other hand, if it spends Rs 27,000 crore in 2024 as well, it will have spent Rs 54,000 crore in total.

And then, there are state elections. Here too, the BJP has outspent its rivals, charged a Raipur-based political observer, saying the party has spent as much as Rs 3-4 crore per seat in Chhattisgarh state polls. “This is cash given to candidates, not what the party spends on social media, etc,” he said.

To put that number in perspective, the expenditure cap for a candidate in a Vidhan Sabha seat is Rs 40 lakh.

In the meantime, India has a total of 4,123 state-level constituencies. In the last ten years, each of them has gone to polls twice. Even assuming an average expenditure of Rs 2 crore across each, that works out to Rs 16,492 crore on Vidhan Sabha elections.

The Wire has asked Agarwal and Bansal to comment on CMS’ estimates, the allegations regarding the party’s expenditure in Chhattisgarh, and The Wire’s calculations. This article will be updated when they respond.

3. Where is this money coming from?

With only the numbers for buildings and campaigning, one ends up with a range between Rs 74,053 crore and Rs 107,803 crore — five to seven times the party’s declared income of Rs 14,663 crore between 2014-15 and 2022-23. What is being caught with electoral bonds is not even 10% of that.

What might the BJP’s expenditure look like?

District offices: Rs 2,661 crore

Other buildings: Rs 900 crore

State elections: Rs 16,492 crore

Lok Sabha elections: Rs 54,000 crore-Rs 87,750 crore

Four points need to be made here.

One. In the absence of information, anybody who seeks to understand the BJP’s finances can only rely on back of the envelope calculations.

Two. Building and campaign expenditure are just two highly visible instances of the BJP’s deep pockets. There might well be other heads of expenditure. Over the last ten years, for instance, the party has used political defections as an instrument to repeatedly topple governments. By March 2021, as the Association for Democratic Reforms reported, 182 MLAs had quit their parties to join the BJP. According to the journalist Sunetra Chowdhury, that number stood at 444 MLAs by March 2024.

In some cases, rival MLAs joined the BJP once the State’s investigative agencies turned their eye on them. In other instances, the BJP has been accused of luring rival politicians with cash. In March this year, Arvind Kejriwal alleged that 7 AAP MLAs had been offered Rs 25 crore apiece by the BJP. In April, Karnataka chief minister Siddaramaiah said the BJP had offered Rs 50 crore to Congress MLAs. Yet earlier, in 2022, Goa Pradesh Congress Committee President Amit Patkar claimed that eight Goa MLAs had been paid between Rs 40-50 crore to defect to the BJP. In Telangana, the CBI is officially investigating a criminal case in which four BRS MLAs claimed they were offered sums of Rs 50 crore and even Rs 100 crore to defect to the BJP.

These allegations, however, have remained in the realm of speculation. Neither investigating agencies, the Election Commission or the country’s political commentariat have established or disproved these charges.

It’s similarly unclear who paid for surveillance on the party’s political rivals and reporters. Forensic tests established that Pegasus was found to have been activated on the iPhone of political strategist Prashant Kishore – then with the Trinamool Congress – during the West Bengal assembly election of 2021. If it was government departments which did this, that is potential misuse of public funds. If it was the BJP, then questions about its financial reserves acquire a fresh layer. Spyware like Pegasus is expensive, costing Rs 3.7 crore per phone infection and a subsequent billing rate of Rs 4.8 crore for every 10 phones.

Incidentally, the BJP is not the only member of the Sangh Parivar that is erecting buildings. The RSS too has been building a brand new office, with 3.5 lakh square feet over 12 floors, in Central Delhi. New buildings are coming up in other cities as well. Photo: X/@811GK

Three. The need for such back of the envelope calculations is itself an indictment of the BJP. In 2014, Narendra Modi and the BJP stormed to power promising to end political corruption. In 2017, doubling down on that promise, they introduced electoral bonds saying they would make political funding more transparent — and ensure parties run on “total clean money”.

Over the last month, both Modi and finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman have reiterated those claims, saying bonds were meant to “clean up electoral financing” and “tackle the use of black money in elections. And yet, do the financial flows described in the party’s annual reports capture all its expenditure?

In the past, the BJP has repeatedly said that its buildings are funded by donations and voluntary contributions by party workers. These, however, would have been already counted – under “voluntary contributions” in the party’s annual reports.

The Wire has asked Agarwal and Bansal if that is the case.

Four. Illicit flows have for long been a staple of India’s political parties’ financing. Think here of the Karnataka contractors who complained of 40% commissions; or the politically connected firms that bag tenders; or parties that extort money from private firms — and, as electoral bonds show, favour firms in return for cash. Parties also run illegal mafias in businesses like alcohol and sand – and face charges of padding up overseas deals.

Each of these modes represents an indirect transfer of money from the public. When roads are poorly built, mileage falls and people pay more for petrol and diesel. When politically connected firms get favoured, other firms go slow on investments, deepening the country’s jobs crisis. When politicians take over businesses like sand and alcohol, state revenues fall. When government departments are subsequently underfunded — out of pocket expenditure on health and education goes up. When overseas deals are padded up, the country ends up paying more. With that, funds again get diverted from more sorely-needed heads of expenditure.

The outcome is a paradox that does not speak well about the ‘mother of democracy’: her children – 800 million of them – need free foodgrain to feed themselves while the parties representing them get fatter.

This article was first published on The Wire on May 2, 2024.

Also Read: Adani Green Energy Ltd Announces Financial Results for FY24