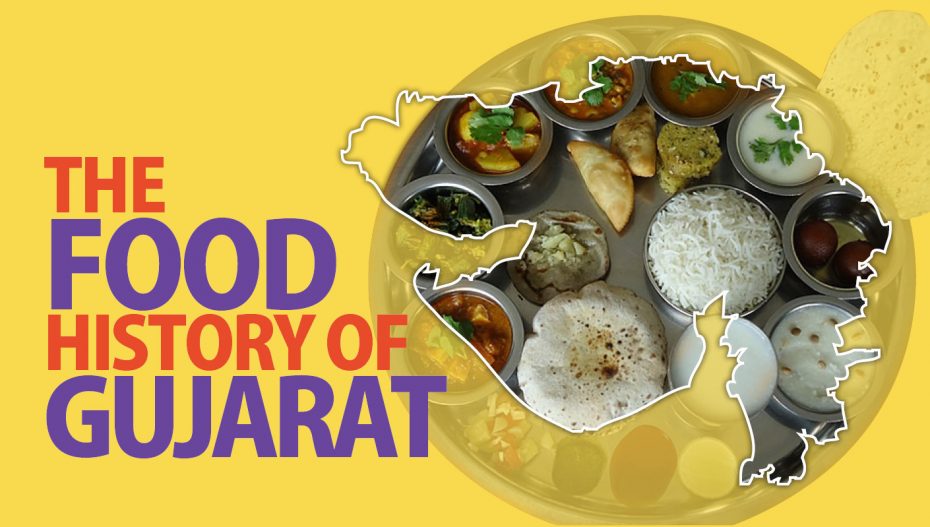

Gujarati cuisine is just like a true Gujarati — a little sweet, a little tangy, a bit hot and a bit spicy — and behind the unique chemistry of food in Gujarat is a whole lot of history and geography!

Gujarati cuisine is not just a gastronomical experience but also rich in nutrition. The special ingredients and ways of preparing a dish vary from location to location, adding to the diversity.

Like elsewhere in the world, cuisine — the dishes and the ingredients — is a window to the rich traditions, culture and ethnic practices of the people in Gujarat, a state whose roots have been traced to the rich Indus Valley Civilisation. Excavations at Lothal and Dholavira, two important ports of the Indus Valley Civilisation, have revealed that the farming of rice along with sorghum and millet was prevalent as early as 1800 BC.

Gujarati cuisine is an amalgam of various tastes. The vast, 1,600 km coastline has been a magnet for travellers from across the globe who brought their own unique flavours and cooking styles. The influence of various ethnic groups and races which at different points of time made Gujarat their home has led to Gujarati cuisine picking up ingredients, spices, condiments, cooking style and flavours from everywhere.

For instance, Gujarati cuisine has been influenced by the cultural heritage of the Persian Gulf countries, even though the interaction was for a very limited period of time. And here again, geography played its part. Before the Industrial Revolution, boats and ships were totally dependent on the sea currents to take them forward. During summers, ocean currents that flowed from the west to east made it very easy and natural for Arab travellers to reach the western coast of India — Gujarat.

In winter, the currents change flow from east to west, which helped these travellers and traders return from India to their countries after a stay of around six months — time enough for the cultural exchange. Hence, there are imprints of Arabic culture, heritage and language on the Gujarati mind, heart and daily life, too. The cultural influences and exchanges which happened when Gujarat became a part of the kingdoms under the Saka, Mongols, Turks, Arabs and Persians, and much later under traders-turned-rules such as the French, Portuguese, Dutch and the Brits were also important.

There are many items on the Gujarati platter now which feel indigenous to the state but were actually brought by foreigners. For example, potato, tomato, chilli and cashew owe their presence in the Gujarati kitchen to the Portuguese who brought these along with them to Gujarat. Even Papad was never indigenous to Gujarat but came from South India and now the biggest manufacturer of Papad in the country, Lijjat Industries, was established and run by a Gujarati lady.

The Gujarati household staple dessert Sheero, too, has its roots in the Arabian countries which prepare Halwa-E- Jamia, the lookalike of Sheero.

The cultural and culinary exchange between Gujarat and the world has not been a one-way street. Khaja from Kutch has played a role in shaping Turkey’s famous Baklava. Try searching for brinjal/aubergine-based preparations in places like Turkey, Italy or even Arab countries and you will be surprised at how much the humble Baingan ka Bharta has travelled.

In a state spread over an area of 2 lakh square kilometres, it is impossible to label one kind of food as authentic Gujarati cuisine. It’s a cliché but it’s true — with every district, one finds a newer variation to Gujarati cuisine. However, four broad labels are possible to pin based on geography: Kathiyawad, Surat, Ahmedabad, and Kutch.

Kathiyawadi Cuisine

Spiciness is a distinct feature of Kathiyawadi delicacies just like Rajasthani cuisine. Like Rajasthan, the Kathiyawad area of Gujarat is not very conducive for farming, especially growing a variety of crops. For example, the very famous Sev-Tameta — sev is a savoury made out of Bengal gram flour and tameta mean tomatoes — resembles the Gatta Ke Sabzi of Rajasthan. Baingan ka Bharta is synonymous with the Saurashtra region and has found a dedicated fan following not only in India but in foreign lands, too.

Ahmedabadi Cuisine

Subedar Ahmed Shah, during the 15th century, built Ahmedabad on the banks of the Sabarmati as a part of the Delhi Sultanate. The influence of Muslim rulers on the lifestyle and food preparations of Ahmedabad is very evident. The Bhathiyaara Gali of Ahmedabad is a perfect example of how Delhi’s Mughlai style of cooking and cuisine has had a very clear influence on Ahmedabad. Just like how a purohit maharaj is associated with traditional cooking in Hinduism, the bhathiyaara are folks who are associated with the cooking at religious places or during social gatherings.

P.s: When we speak of Ahmedabad, we do not mean Ashaval or the Karnavati Town, but take into account the modern-day Ahmedabad.

Surti Cuisine

As the saying goes, if you’ve never had a meal in Surat you’ve never experienced food in India.

Once upon a time, a flourishing port of South Gujarat, Surat is famous for its Nankhatai which is a perfect example of how the Dutch have left their influence here. A Dutch trader, while keeping in mind the needs of his people living in Surat, had established a bakery that was later on taken over by the Parsis, who mingled their Iranian culture into the traditional Dutch baking. Thus was born Surat’s famous Nankhatai.

Also in Surat, the Barah Handi (12 bowls) at Jhanpa Bazaar offers you a Mughlai experience reminiscent of Delhi. And how can one forget the famous Surati Ghari, which is especially consumed on full moon night just a fortnight before Diwali. Surat’s Ghari has an interesting origin story. It is said that in the year 1857, during India’s first war of Independence, Tatya Tope and his troops had taken shelter in Surat and Dev Shankar Shukla, in an attempt to feed Tatya Tope’s men with food that would give them the stamina and energy to continue their battle, prepared the Ghari on a full moon night. Hence the tradition of having Ghari on Sharad Purnima, the full moon night before Diwali.

Kutchi Cuisine

Exploring the Kutchi cuisine became a special interesting aspect because the origin of Kutchi food leads us to Dholavira, one of the cradles of the Indus Valley Civilization which has recently been declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Millet in paddy and rice has been a staple of the province for over 2,000 years. The cuisine has undergone several exchanges of hands depending on the many travellers, traders and invaders who entered from northwest corner of the province at different times. Kutch has the largest coastline of India.

Since Kutch is mainly a dessert, the arid climate has a direct influence on the food and the local cuisine. The scarcity of green vegetables is a highlight of this region and is reflected in the food.

One can find traces of the dish ‘Khaja’ in the Turkish dish Baklava. During the medieval era, about 400 – 500 years ago from the Balkh province of Afghanistan, a sweet dish started to enhance the food experience at homes in Kutch. The melt-in-the-mouth dish ‘mesuk’ got it first Indian influence in Kutch. And yes, we made it quite a bit more sweeter than the original Afghani dish.

Mesuk, made from besan, ghee, pistachio and sugar is a popular dish of the region today and the same Kutchi Mesuk is known as Mesukpak in North India and Mysore Pak in South India.

But the regions palette is incomplete without mentioning its most sought-after dish -Dabeli. Post-independence in 1960, it was invented by Kesha Malam who was selling this dish on a hand cart on a street. Dabeli literally means to suppress, and this all-in-one dish is an amalgamation or mixture of spicy, sweet, tangy and fruity flavours suppressed together with mashed potatoes and served inside a pav or bun. Dabeli rules the menu list at Kutch’s Rannotsav.

Green Cuisine: Gujarat and vegetarianism

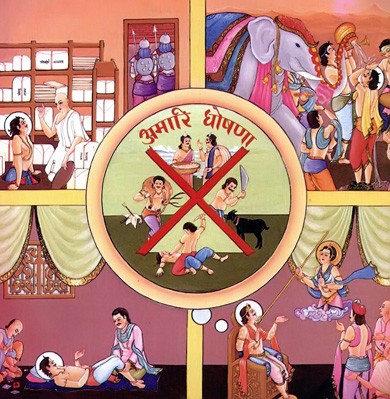

Gujarati cuisine is mostly vegetarian. If one has to attribute a factor to this preference, then it has to be the influence of Jainism, and Vaishnav religious practices. In the 11th century, under the influence of the Jain Guru Hemchandracharya, King Kumarpal had given up meat and had pronounced a ban on all kinds of meat eating in his kingdom, which was popularly known as Amarighōshanās.

Pushtimarg, which worships Lord Krishna, came into practice in the 15th century and gained popularity in Gujarat after Vaishnav Guru Vallabharyacha’s son Guru Vitthalnath travelled far and wide, spreading the religion. Most of those who practised and followed Pushtimarg were traders and rich businessmen like Surat’s Virji Vora and Ahmedabad’s Shantidas. They used their wealth to spread the religion and its practices, including curtailing meat-eating.

What Gujarat ate during Medieval Period

Staple diet: Khichdi (Porridge) prepared using rice/sorghum/millet, Dhokla, Idada, Khandvi, Raita, Puranpoli, curd or buttermilk.

Sweets/Desserts: Laddoo prepared from arhar, Bengal gram, roasted Bengal gram, millet, gol papdi (jaggery preparation), Ghevar, Suttarpheni, Shakkarpara (sugar syrup preparation), Magaz.

Vegetables: Tindora/Cocccinia, vaalor (Indian beans), chibhda (white gourd), choli (amaranth leaves), gavaar (hyacinth beans), karela (bitter gourd), aamla (Indian gooseberry), tuver, mula (radish).