I must admit, I was shocked when I heard the news that Citibank is planning to exit consumer banking in India. For those of a certain vintage era, Citi is an iconic organization, once considered the best job on business school campuses, offering Indians a global career. Citigroup even had an Indian-American global CEO in Vikram Shankar Pandit for five years, till 2017. So the unexpected announcement from the new CEO, Jane Fraser, that Citi plans to exit 13 countries, including China and India, made me sit up.

I called some of my IIMA batch-mates to check if they were as surprised as I was. Most of them were, but at the same time, they pointed out that Citi has lost much of its sheen over the years. It long ago lost its ranking as the top job on campus – that now belongs to one or the other of the global consulting firms. With the rise of banks like HDFC, ICICI, Axis, and Kotak, it has become a minor player among the private sector banks. Even in the business of credit cards, where it was once the only game in town, Citihas ceded market share to Indian banks. Citibank, it seems, might just quietly fade from India’s collective memory.

I remember doing a project on corporate perceptions of foreign banks in Kolkata as part of my summer IIMA internship in 1990, where it emerged that Citi’s positioning was distinct from others like Standard Chartered and HSBC. It was seen as an adventurous American cowboy, not necessarily the best image to have in the staid world of banking.

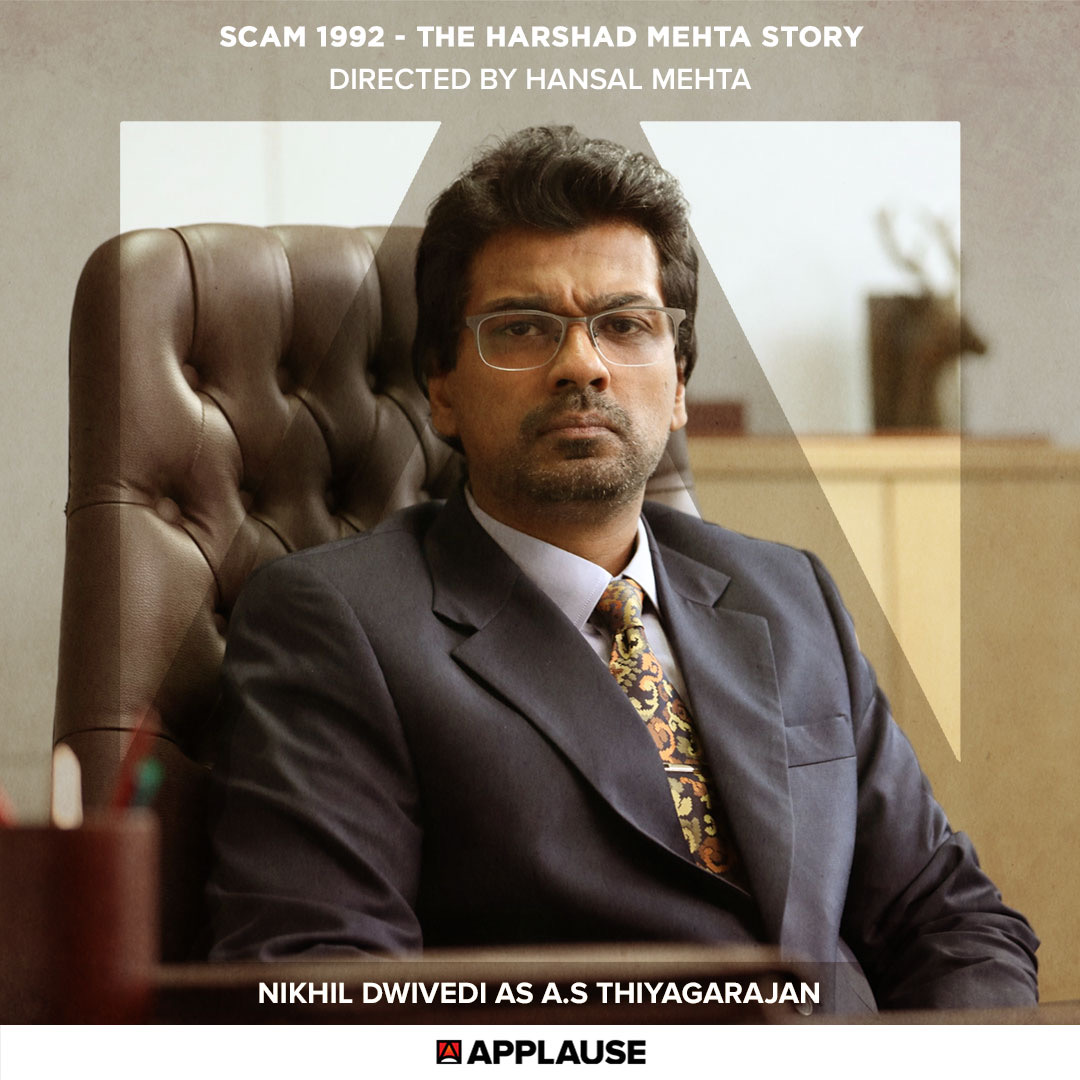

The perception would prove to be on the mark two years later, with the Harshad Mehta scam. In the hit series Scam 1992, Citi is depicted as a villain, albeit one that the less profitable public banks longed to emulate. Citi’s Indian operations took a hard knock from the scandal but the bank proved to be remarkably resilient, regaining its verve and pioneering a new range of businesses in India, including IT services and consumer finance. Citi even got around the RBI restrictions on the number of branches it could have as a foreign bank, by setting up a large network of ATMs, which were then new technology in India.

Despite regulations that foreign banks were subjected to, Citi came to dominate the Indian banking sector with the aforementioned innovations. One product it was the undisputed leader in was credit cards. Much to my mortification, my first application for a Citi credit was rejected. Two years later, it launched a co-branded card with The Times of India, then my employer, and for the first time, I had myself a credit card.Citi had by then decided to take more risks in its card business to include a clientele that others considered unsafe. The idea was that “safe” customers used their credit cards like charge cards, paying up all their dues at the end of the monthly cycle, which is never very profitable for the bank. Citi was willing to take a bet on those who rolled over their credit, which expanded the market enormously.

Citi was a risk-taker in the employee space too. With their high salaries, and perks like housing, foreign banks were the favorites on IIM campuses, but most of them sought candidates with “pedigree.” Citi, on the other hand, started to recruit smart young people without taking into consideration where they came from or who their parents were. In the process, it promoted an intensely competitive work culture where average performers soon found themselves reporting to their former juniors. The top performers, for their part, were promoted to positions in global financial centres. Some, like Aditya Puri on HDFC Bank, moved on to the newly emerging Indian private sector banks.

By the mid-90s, Citi had been overtaken on the B-school campuses by banks that offered fresh recruits direct posting on Wall Street. Indian talent had made a name for itself globally, a process that was started by the likes of Citi.

Citi today has abandoned the idea of being a global entity, one that “never sleeps.” But the process of exiting India is not likely to be quick. The bank still has a large number of clients and the RBI will not allow them to be left in the lurch. Buyers for various businesses have to be found; assets, including its branch network and employees, have to be transferred. Whether these will go to a foreign bank or an Indian bank remains to be seen. Citi has been in India for 120 years since it started operations in Kolkata in 1902. It can take its time making a proper exit.