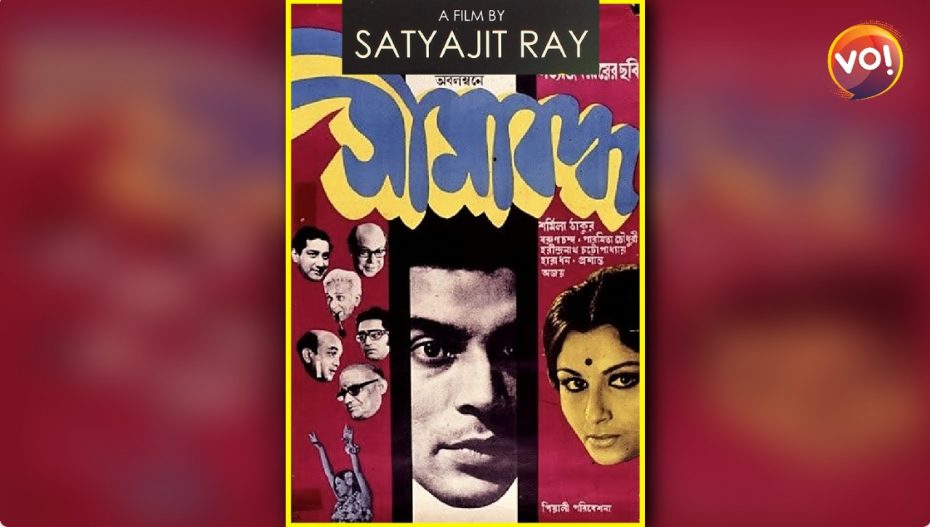

If it is easy to incite violence in Bengal, today, it would seem it was even easier in the 1970s, as films like Seemabaddha reflected. Satyajit Ray’s national award-winning film, set in 1970, shows how stooges of a vested management, could cause the lockout of a factory, by creating unrest and a bomb blast, over something as trivial as the size of fish pieces served in the workers’ canteen.

Hindustan Peters is a lights and fans-making company, with a profitable export division selling fans to countries like Iraq. Shyamalendhu Chatterji, played by Barun Chanda, is the upwardly-mobile Sales Manager of its fans’ division which he joined in 1960, on a salary of Rs.800. A blue-eyed boy of his British bosses, Chatterji leads an elite, white-collar lifestyle that was typical of managers working for multi-national companies in Bengal before labour discord caused most of them to re-locate to other states.

This lifestyle revolves around a stylish home, clubs and race-courses. Appearances are important and Chatterji, a khadi-clad school-teacher once, takes care to keep up with his colleagues, even playing golf on Sunday mornings though he doesn’t quite enjoy the game. Rising rapidly in his job, ten years down the line, Chatterji is in the running for a post on the Board of Directors. But…an unfortunate twist of destiny almost eliminates him from the race.

A consignment of fans for Iraq is found to be defective just a fortnight before its delivery date, March 15. Rectifying the defect would mean a delay in delivery. And, not delivering on time would entail not just a penalty, but a serious loss of face, too. This could cause the director’s post going to Chatterji’s closest competitor, from the lights’ division. How does Chatterji tackle the crisis? Taking advantage of a clause in the contract that allows additional delivery time if there is a natural calamity like an earthquake or a problem in the factory, Chatterji, guiltlessly, ropes in the Labour Officer, Talukdar, to manipulate a lockout in their factory. Talukdar, a smooth operator, played very convincingly by Haradhan Bannerjee, has men to do the dirty job. So, while a few workers are provoked into agitating over the size of fish served in the workers’ canteen, and causing the agitation to blow out of proportion, there are others to toss a bomb inside the factory, forcing the

management to halt all work and padlock its gates.

Immediately after this, Chatterji is seen with his wife (played by an innocent-looking Paromita Chowdhury) and sister-in-law ( a coquettish Sharmila Tagore ) at a restaurant, enjoying a hearty meal and a cabaret artiste’s sensuous moves. There is no trace of worry about the Iraq consignment or Tiwari’s life.

On March 19, the management signs a deal with the workers to re-open the factory; and Chatterji is unanimously inducted on the Board of Directors. In a quid pro quo gesture, Chatterji assures Talukdar that he has recommended him to the Managing Director, for a promotion. Mission accomplished, Talukdar peels off the sticking plaster from his cheek.

Satyajit Ray’s film made in 1971 reflected the industrial climate of the times, when a certain brand of ideology was a convenient tool to blackmail managements, without significantly improving working conditions. Present-day Bengal seems no different. Ideologies may have changed and the sticking plaster replaced with a wheelchair, but the common man’s plight is the same. Perhaps worse. Because, over the years, most industries moved out of Bengal or were forced to relocate, like the Nano plant. Unemployment continues to soar while political parties play dirty games to outwit each other. The worker is the last person on anyone’s mind. Seemabaddha is, therefore, a telling narration of times then, and now. Definitely worth viewing again.

Excellent summation of a film and the ethos of an age. Things have changed since the time when militant trade unionism was rife but one suspects the changes are skin deep. Avarice, expediency and cynical disregard for ethics… All that’s up and running as before.