Using samples from archaeological sites, scientists have found that all South East Asians are descended from the Harappan civilisation. Archaeologist and author Vasant Shinde who played a lead role in the excavation of Harappan sites like Rakhigarhi in Haryana, believes this data can serve to unite the nation.

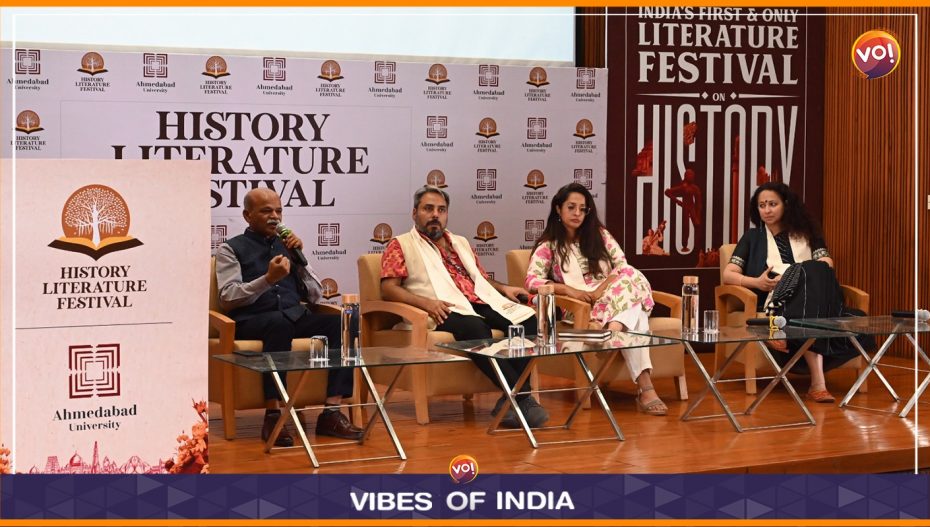

Addressing a session on “The Tools of History” at the History Literature Festival (HLF) at Ahmedabad University on Saturday, Dr Shinde stressed the fact that that Hindus and Muslims in India have the same DNA. “Any regional variations in the way people look in India are on account of food, climate and mixing with other ethnic groups from Iran and Africa,” he said.

Dr Shinde, who is the founding Director General of the National Maritime Heritage Complex in Gandhinagar and former vice chancellor of Deccan College, Pune, also made a case for the Harappans as a non-violent people who practised meditation and yoga. “I have been criticised for presenting findings that favour BJP ideology. But my findings are based on scientific data and people should believe scientific data,” he said.

Still, many in the audience were sceptical, some vociferously so. Sensing the mood, moderator Amit Arora, who is one of the prime movers behind the HLF, asked the panellists: how do you keep the story real and guard against misinterpretation of data? Archaeologist Disha Ahluwalia, who is currently working at the Rakhigarhi site, answered by saying archaeology is a physical science that does not leave much room for misinterpretation. “Each time we excavate, we go in with a specific research agenda. This season, we are trying to understand land use patterns,” she said.

Professor Trivedi also spoke of how the princely states provided scholarships for students to study at the world’s best Universities in the 1920s. “Bhavnagar state, for example, sent students to MIT. The idea was that would return and contribute to the nation-building process upon returning home,” she said.

Fellow panellist Tana Trivedi said the best way to get your facts right is to cross check and verify. Professor Trivedi, who teaches business history at Ahmedabad University and is currently archiving the papers of Prabhashankar Pattani, the late divan of the princely state of Bhavnagar, gave an example from own research: “In the Pattani archives, I found a story of one Sundarji Saudagar, a 19th century horse trader of Kutch who bought horses from Afghanistan for the British, who used them in their battle against Tipu Sultan in Mysore. I later found a passing mention of the same Sundarji in another, wholly different paper, which helped verify the story.”

The Pattani archives also contain documents from numerous meetings of the officials of the princely states, where Federalism is discussed as a political structure for independent India. “If we had gone ahead with this, India would have remained a dominion and there would have been no clean break from British rule,” said Professor Trivedi.

Indeed, the panel discussions at the HLF came up with several such imaginative “what if” scenarios. Speaking at the first session on “The Tale of Two Empires: The Maratha and the British,” Professor Chinmay Tumbe of IIMA speculated on what might have happened if the Marathas had not fought the Battle of Panipat and stayed below the river Chambal. “West and East Pakistan would have been joined by a swath of territory in the Indo-Gangetic belt,” he said. “If the British hadn’t prevailed in India, the HLF would be conducted in Marathi or Persian.”

Besides the English language, British rule is credited with giving India the railways, a postal system and modern political institutions, but Professor Amar Farooqui of Delhi University, said this would be a strange way to assess the effects of British rule. “There is nothing particularly British about these things. They are the hallmarks of any modern state,” he said.

Professor Farooqui, who is the author of “Sindias and the Raj,” said the ascent of the British through the East India Company may have its roots in trade, but then again, business has always been linked to politics and diplomacy. “Even modern day MNCs look for political leverage that might gibe their business a competitive advantage,” he said.

But can the Marathas really be compared with the British? Or as Professor Tumbe asked, were they really all that great? Uday Kulkarni, author of “The Maratha Century,” said that Historians have unfairly brushed way the Marathas, giving the impression is that the Mughal empire gave way to the British. “The Maratha century saw power shift from the King to the Prime Minister and finally to the army Generals, which the British exploited. But the Maratha contribution to the country is considerable,” he said.

But what of the Maratha plunder of Bengal and Orissa, which rankles to this day? “The Marathas followed a scorched earth policy in East, but they never indulged is senseless massacres. The former Nawab of Bengal asked for their help when Alivardi Khan usurped the throne,” said Dr Kulkarni.

One of the more engaging sessions at the HLF was on “A People’s History of Language,” where the panellists talked of the death of multilinguality and small languages. Moderator Rahul Sarwate of Ahmedabad University pointed out that in their time, Vinoba Bhave knew 16 languages and Mahatma Gandhi knew 10, but today, most people are content knowing one. Is it possible to save Indian languages from the onslaught of English? Is it practical to teach engineering and medicine in the local language?

Peggy Mohan, author of Wanderers, Kings, Merchants: The Story of India Through Its Languages,” said that if a small country like Iceland has been successful in doing it, there is no reason India cannot. “It is a political decision. I may not like the politics that go into this decision, but it can only become an issue through politics. In India, you are cut off from technology if you do not know English,” she said.

Ms Mohan said that just as English is the high language today, Persian was the high language of the Mughals, who were actually from Uzbekistan. “They dumped the Uzbek language completely. Language is tied to politics and sometimes you have to let an old language die. In the Caribbean, where I come from, the Hindus say they want to keep their own language. But this will have political repercussions, there will be a backlash. You cannot prop up languages out of sentimentality,” she said.

Historian Prachi Deshpande, who teaches at the Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Kolkata, said the standardisation of languages has been seen right from the Middle Ages to Modern times. “The State tries to make things uniform, while on the ground, people talk differently. Colin McKenzie, a British surveyor, left behind an archive that showed a profusion of scripts and languages during the time of Tipu Sultan.”

Ms Deshpande spoke at length about the Modi script, which was used by the business class for keeping accounts. “Modi is a cursive script which made for swift writing, but it was illegible to outsiders. A small group of scribes had control over it. The British killed it because they could not interpret it. But now there is a revival with many young scholars interested in learning it,” she said.

The penultimate session on “Science & Technology and the Making of Modern India,” featured a discussion on the rise of the pharmaceutical industry, the Nutan Stove and the portrayal of scientists in OTT secrials like Rocket Boys. Here too, there were some speculative questions like, what would have happened if we had liberalised the economy in the 60s instead of the 90s. According to author Dinesh C Sharma, India could have become an outsourced manufacturing hub like China is today.

Also Read: Delhi Police At RaGa’s House Over His Remark On Sexual Assault Survivors