Days before her assassination, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi had apparently communicated to then President Giani Zail Singh to have Rajiv Gandhi sworn-in “if anything happened” to her.

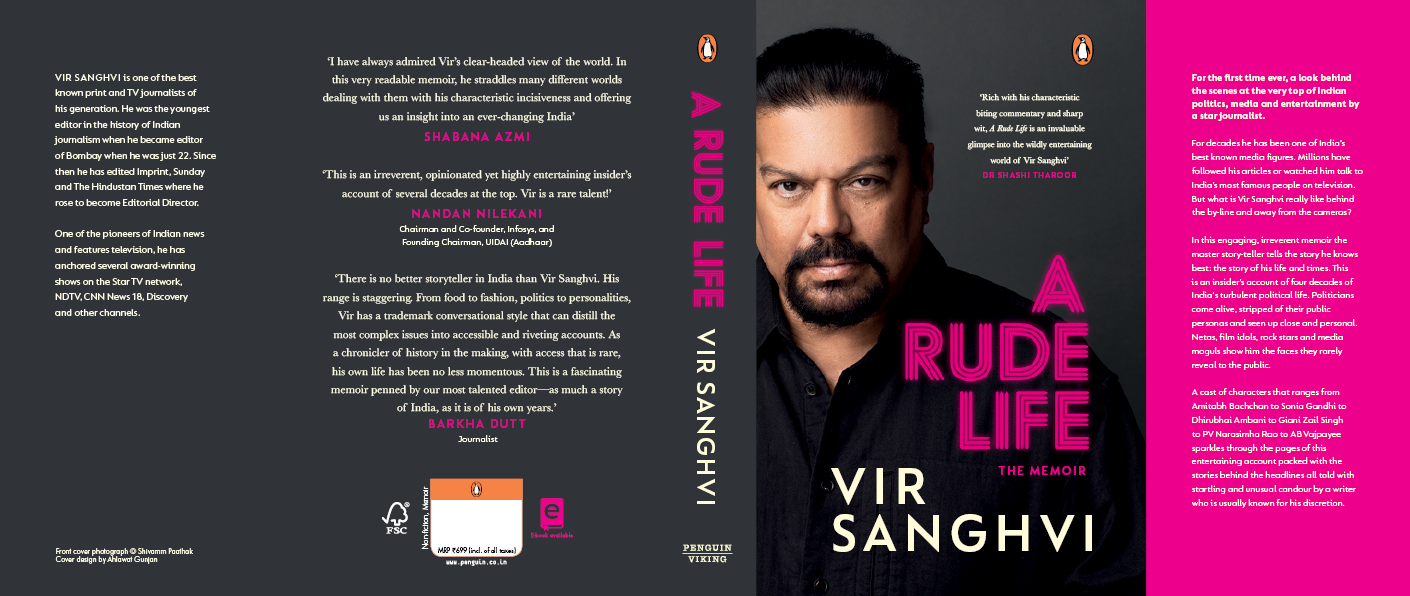

In his riveting, soon to be published autobiography, A Rude Life — The Memoirs (Penguin Viking), author-columnist Vir Sanghvi has written that Zail Singh told him that Indira was aware of the threat to her life following Operation Blue Star of June 1984, and asked the President to “swear Rajiv in before the Congress had a chance to react”.

Vir was then the editor of a Mumbai — then Bombay — magazine, Imprint. The revelation is startling, as Zail Singh had uneasy ties with Rajiv Gandhi throughout his presidential years. At one point, the President is said to have contemplated dismissing Rajiv, which could have led to an enormous and unprecedented constitutional crisis.

Zail Singh, according to Vir, had an explanation about why Rajiv did not like him. “He had hated Pranab Mukherjee and R K Dhawan, too, because Indira Gandhi trusted their judgment more than his.”

Giving a vivid yet crisp account of his meeting with Zail Singh, Vir describes the scene at the Rashtrapati Bhavan’s private quarters.

“Zail Singh sat on a bed. He had removed his turban and seemed weak and helpless, nothing like the president of the world’s largest democracy is supposed to look… He explained how he had sworn Rajiv in as prime minister. Mrs [Indira] Gandhi, he said, had told him that if anything happened to her (and she knew that she was under threat), he was to swear Rajiv in before the Congress had a chance to react.”

President Giani Zail Singh was away in Sanaʽa, the capital of Yemen, on October 31, 1984 when Indira Gandhi was assassinated by her security guards at her prime ministerial residence. Singh received a call from Delhi informing him of the shooting and asking him to return immediately.

Before Singh’s plane touched down at the Palam airport on that fateful afternoon, there was buzz that a senior Congress leader Pranab Mukherjee had emerged as a contender for the prime minister’s post. Mukherjee was the officially designated number two minister in Indira’s cabinet. Mukherjee was expelled from the Congress in 1984 for allegedly showing “defiance” towards Rajiv.

In his memoirs, Mukherjee had dubbed the entire episode as “a case of misunderstanding” that was cleared when Rajiv brought him back into the Congress in 1988.

Speaking to Vir, Zail Singh admitted that he was not allowed to go out on streets and assure Sikhs in Delhi. According to Zail Singh, the government was scared that Singh would come out in public and say that Sikhs were being butchered.

“If I had resigned then,” Zail Singh told Vir, “how long would this government [Rajiv regime] have lasted?’”

Vir claims to have narrated his own conversation with Chandra Shekhar, who later rose to become the prime minister, to Zail Singh to substantiate that the president’s anguish was not an isolated experience.

Chandra Shekhar’s son had a Sikh friend who was in danger during the anti-Sikh riots.

Chandra Shekhar immediately called Narasimha Rao, the then Union home minister, and asked if he could arrange for police protection for the area where his son’s friend said Sikhs were being murdered, and a police escort for this family to come to Chandra Shekhar’s house.

Vir has quoted Chandra Shekhar as saying: “Rao responded, ‘No, no. It is very dangerous, Chandra Shekharji. Tell your son not to allow any Sikhs into your house. Too dangerous.’”

Vir’s memoirs are full of such anecdotes, tales and gems. One nugget is about Chandra Shekhar’s Bhondsi Ashram farmhouse in Haryana. This was in early 1991 when Chandra Shekhar was prime minister surviving on the Congress’s support from outside.

The barren, rocky and soulless Bhondsi was converted into a dreamscape — with hillocks and lakes and fresh air that acted like a tonic for visiting Delhi wallahs.

Protocol dictated that the prime minister arrives last, so Rajiv reached the drinks area —he drank soda water — a few minutes before Chandra Shekhar was due to arrive. When some referred to Chandra Shekhar’s favourite place for place for parties and official conclaves as an ashram, Rajiv looked incredulous.

“It’s not an ashram. It is a country club,” Rajiv is said to have commented loud enough for anyone standing nearby to hear.

Even as Vir mumbled something in Chandra Shekhar’s defence, Rajiv asked him: “Have you heard the story about Brezhnev?”

Rajiv’s “joke” still has a ring of relevance. It goes like this:

Brezhnev’s mother comes to visit him. He tells her she should be proud of him. He shows her his dacha. He shows her his many fancy cars. He shows her his luxurious living quarters. To his surprise, his mother starts to weep. Brezhnev is surprised. ‘Aren’t you proud of me, mama?’ he asks. ‘Oh Leonid,’ she says through her tears, ‘What will happen to you if the communists come back?’

Vir’s account on the Harshad Mehta scam is most telling. Mehta was a stock broker, lionised by the media and nicknamed The Big Bull. Fawning newspaper profiles and magazine cover stories hailed him as a genius. By 1992-93 Mehta was accused of defrauding banks and manipulating markets, which came to be known as the Harshad Mehta Scam. The market crashed and the middle class lost what it had invested in the boom phase.

Mehta had levelled sensational allegations against Prime Minister P V Narasimha Rao, accusing him of accepting Rs 1 crore as bribe in person. A big debate had followed whether Rs 1 crore could fit in a suitcase that Mehta had allegedly handed over to Rao inside the prime minister’s residence.

Vir was familiar with the prime minister’s residence at Race Course Road in New Delhi. He questioned Mehta closely. “When he got every detail of the encounter and its setting right, and even produced the visitor’s pass that had been issued to him by reception at Race Course Road, I knew he was telling the truth to the extent that he had clearly been there and met Rao,” chronicles Vir.

He then raises the question, “But had he handed over the money?”

“Mehta in order to prove his point and counter a practical objection: could a crore of rupees fit into a suitcase? Arranged for another (similar) suitcase and a crore in cash and shot a video to demonstrate that it was indeed possible to carry all that money in a single suitcase.”

Rao remained unfazed and completed his term as prime minister in 1996 while Mehta languished. He was kept on trial for nine years, until he died in 2001.

Nice information, lesser known…