Natarani plans to end the winter season on Saturday with a Usha Uthup concert, which is already sold out. Before the big bang concert however, it served up something more cerebral last week, in the form of two minimalist plays: After All, a solo show by Solene Weinachter from Scotland and Anandowari, a Hindi play on the life of the 17th century bhakti poet Tukaram, from Mumbai.

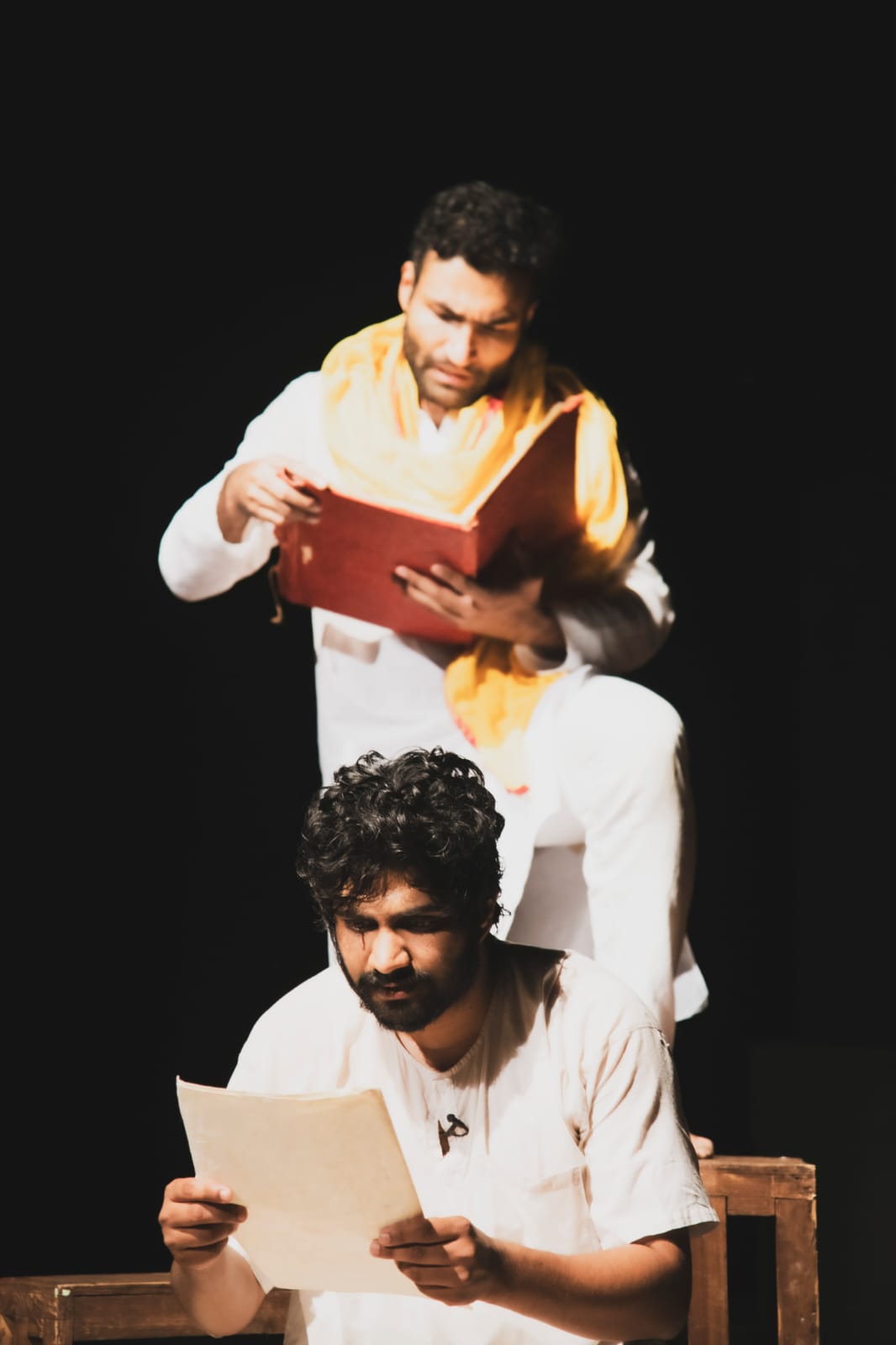

Minimalist theatre is generally bereft of sets and the actors use only a few props, leaving it to the audience to imagine the setting. In Anandowari, the props consist of two stools, which the two actors sporadically sit on, stand on and carry around. Based on the novel of the same name by Marathi litterateur D B Mokashi, it tells the story of Sant Tukaram, who lived in the time of Chatrapati Shivaji and still has a huge following.

Tukaram often wandered into the jungles around his village to commune with God, but the last time he did this, he never returned. Anandowari tells its story through Tukaram’s brother Kanha, played by the talented Varad Salvekar, as he searches for the missing poet. Keeping him company on stage is Hrishab Kanti, another very talented actor, who plays Tukaram, as he appears to Kanha in his dreams.

Minimalist theatre is actor-driven by its very nature and as the play progresses, the two actors play a range of roles from the people in Tukaram’s life. Director Gerish Khemani has deliberately chosen to cast two young men in the lead roles though Tukaram was close to 50 years old when he died. The play is dialogue driven, but there is action that spans the whole stage as two actors, one clad in a dhoti, the other in pyjamas, move around vigorously, sometimes falling to the ground, sometimes into each other’s arms.

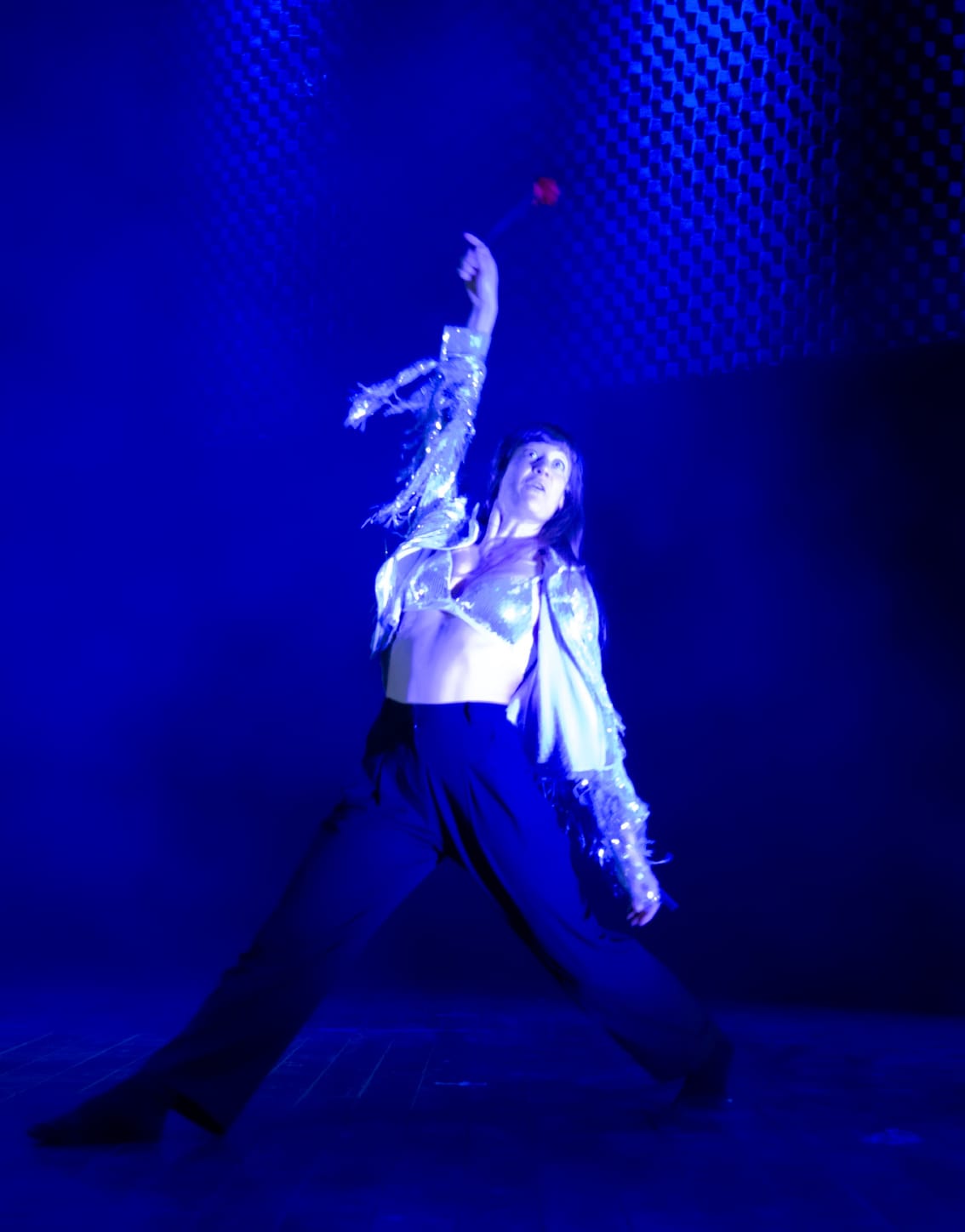

After All, the other play staged at Natarani last week, is a solo show, produced, written and performed by dancer Solene Weinachter from Scotland. In her introduction, Natarani director Mallika Sarabhai said the play is about death, but really, that gives it too much gravitas. Solene’s ruminations on death, such as they are, are light and mostly about the rituals that surround it.

Solene starts her performance by narrating how she went to her Uncle Bob’s cremation ceremony, where they played the song My Way and her father asked her to dance with him. That leads her to think about her own life and how she might be remembered after she dies, especially since she has no children. At one point, she very sweetly asks the audience, in her French-accented English, if we would remember her performance at Natarani even after she dies.

Solene talks about the keening ritual in Scotland, which is akin to the Rudali tradition in India, where professional mourners perform at funerals, though she does not draw the parallel. But then again, her script is not meant to be scholarly. Solene is a professional dancer and the best parts of After All are when she is dancing. At one point she dons a sequinned jacket and dances to Donna Summer’s I Feel Love.

There is also a lot of audience connection. In a prelude to her performance, Solene distributes plastic roses to those sitting in front and mid-way through the play she asks them to throw the flowers on stage. After All ends with her sitting in the audience as a knocking sound backstage calls to her to end the show, but she does not want to go. That sounds rather dark, but the way it’s done, it isn’t.

Also Read: Bespoke Art Gallery Organises Demo by Swiss Sculptor