Interestingly, the term “Impressionism” has it’s origin in an insult. The snooty art critic of the day did not approve of the style adopted by a group of artists in a direct affront to the style prevalent in that age. Louis Leroy, a critic pejoratively used the word “impressionism” to denote the ” “Impression, Sunrise” of Claude Monet when it appeared to the public for the first time in 1874.

It was not new, Gothic, Mannerist, and Baroque styles when it first appeared were ridiculed before they chart out their own distinct destinies. Monet and his anti-establishment friends took the mockery as a badge of honour and went on to create amazing works of art in defiance of set rules.

What the impressionists were rebelling against was the unsaid diktat of the Académie des Beaux-Arts in Paris and it’s viewpoint as to what art should look like. The Academie, the French school of high art taught young artists the fine arts. It saw itself as the sole forebear of the aesthetic standards in art, a view largely shared by most in the artistic world. It also imposed the methods of art at the time.

The traditionalist establishment of the Academie favoured the painting style based on the ideas of the Renaissance. The style came t be known as Academicism. It was all about strong outlines, clear composition, correct shading, and linear perspective.

The first sound of straying steps was heard when J.M.W. Turner and Gustave Courbet went against the principles of Academicism and produced work using different methods than an established practice.

Gustave Courbet’s interest in ordinary subjects is depicted in the painting below.

Later in the 1860s, a group of young artists who were learning the Academic style decided to go astray. The names included Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Alfred Sisley, and Frederic Bazille with slightly older Edouard Manet as their leader.

The fundamental difference in style of the impressionists was their preference for colour rather than outlines and perspective. The paintings were more vivid in colour and brighter in appearance than those done in the Academic style. In the method of impressionists, colour came first in contrast to Academicism, where a perfect sketch was required first to be filled with colour later.

The history of art is replete with the eras which overthrown earlier styles, often co-existing with and at times overpowering the old.

Claude Monet and his contemporaries were walking in the footsteps of the great Titian and others in the renaissance of 16th-century Italy. Titian and his friends, the artists from Venice went against the style perpetuated by the great artists from Florence, Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Raphael. The Florentine greats had an emphasis on lines, contours, and forms in their work, the Venetians were all for colour and its effect.

Significantly, the Impressionists later painted Venice showcasing rare brilliance, as if paying tribute to the forefathers of their artistic style.

As in these two paintings of the Grand Canal, by Monet and Manet respectively.

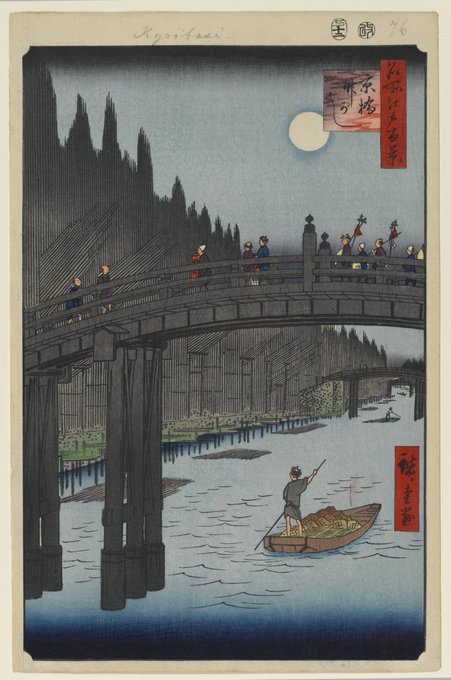

Japanese woodblock prints, which had started coming into Europe had also inspired the impressionists. Impressionists started painting ordinary subjects, used bold colours, and made compositions with angles that would not be approved of by the Academie. For example, the composition in “Two Dancers” by Edgar Degas, features poses completely unlike the Academicism

Though the methods and styles were distinct from each other, the Impressionists, just in a similar manner to the Academy, were still depicting reality. It was not abstract. However, when Academicism was more of a formal painting, with carefully designed lighting and orchestrated placement of subjects.

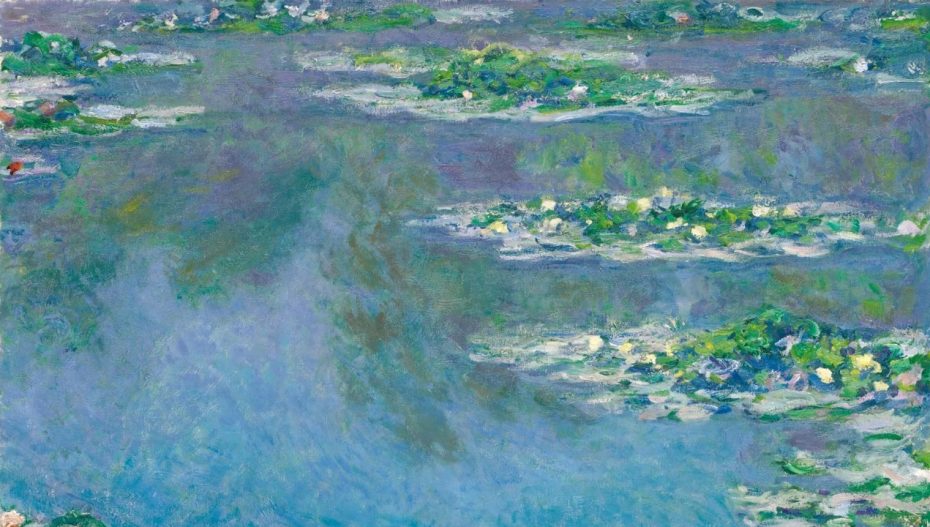

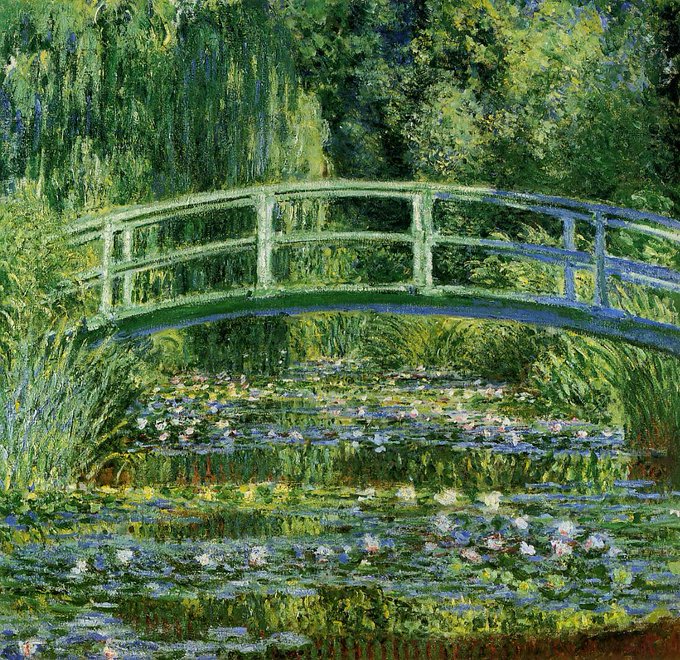

The impressionists’ art was more fluid and informal than depicted by the art taught at the Academie which was more straightjacket and had a closeted, studio-like feel. There was a lot of movement, glimpses, suggestions, mist, smog, and a plethora of perspectives. If we look at Monet’s famous paintings of lilies and the bridge in his garden, there is nothing unrealistic, yet it has that particular feeling of overflow beyond frames.

The Impressionists painted great outdoors. They painted what they saw -such as a cathedral in different shades of light across several seasons, a blue sky, and sun rays on flowing water.

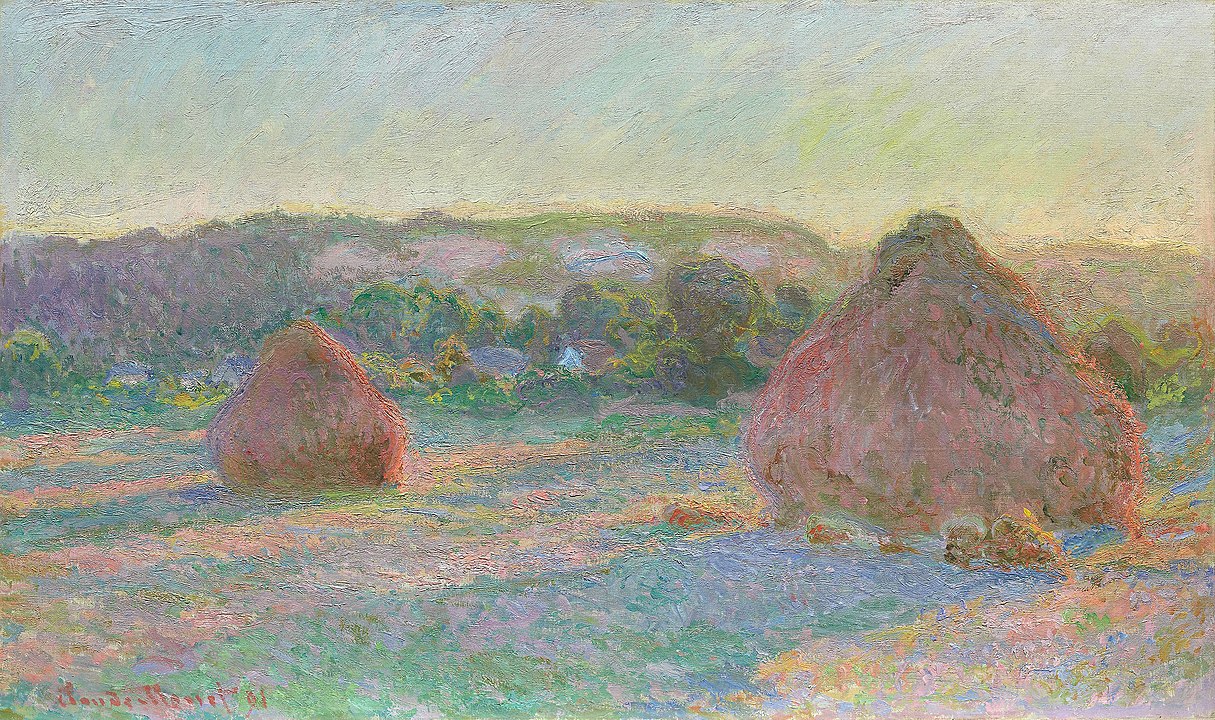

The visible brush strokes and blurred colours of Haystacks below by Claude Monet are a visual treat.

Naturally, the Impressionists, being at odds with the established practice, caused such a stir. The change also was visible in choice of themes. Academicism was about Classical, and Biblical themes, such as the Birth of Venus, which was painted over and over again by artists of different eras.

The Impressionists, however, were interested in everyday subjects. Take for example Pissarro’s Boulevard Montmartre or Monet’s Gare Saint-Lazare. The term coined as an insult had triumphed against the Academie and garnered much popularity and influence.

Later, Impressionism spread into several other artistic movements also. It went beyond the hegemony of the Academie and opened the windows of possibilities. Art had emerged out of the closet, leaving her chains behind. As rightly said by E.H. Gombrich, the story of art is not one of linear progress but of constant change, imitation, and reaction.

Further down the evolution path, Post-Impressionism saw the symbolism of Paul Gaugin, cubism of Cezanne and the swirls of Van Gogh. It used more of distortion and bright colours. It continued what impressionism started- to feel the art, in lie of to see the art.

Courtesy: Twitter @culturaltutor