In 2017, he was anointed as the chief minister after his cheerleaders staged a show of strength on the streets when the BJP chewed over names to lead the legislature party. In 2022, he was elected as the chief minister painlessly because it was thought he had “earned” his spurs over the past five years. However, Yogi Adityanath, who was sworn in as Uttar Pradesh’s Chief Minister for a second term—the fifth incumbent to win the honour in three decades—his real test begins today if he is to evolve as a serious contender in the national sweepstakes for power.

The operative word is governance and Adityanath’s governance is expected to be under scrutiny in every sphere. In his first term, he passed off as a “novice” in administration although he controlled and steered the working of north India’s most powerful monastery, the Gorakhnath Math, and represented Gorakhpur in the Lok Sabha uninterruptedly from 1998 to 2014. He won the election principally on the claim of straightening out UP’s law and order but his assertion was loaded: the government’s methods and modalities of law and order management were directed against the minorities to beam a political message for the Hindus. The messaging worked to Adityanath and the BJP’s advantage.

This time, the chief minister is confronted with a host of issues which were flagged by the Opposition in the election campaign: agrarian distress, joblessness, filling in the long-pending vacancies in government departments, containing migration, universalising irrigation, stemming price rise and so on.

However, the biggest challenge before Adityanath is to try and harmonise his equation with the Centre and the UP BJP, both of which were patchy over the last five years. A common complaint from the UP BJP was the chief minister and his apparatchiks were “inaccessible” even to the MPs and MLAs.

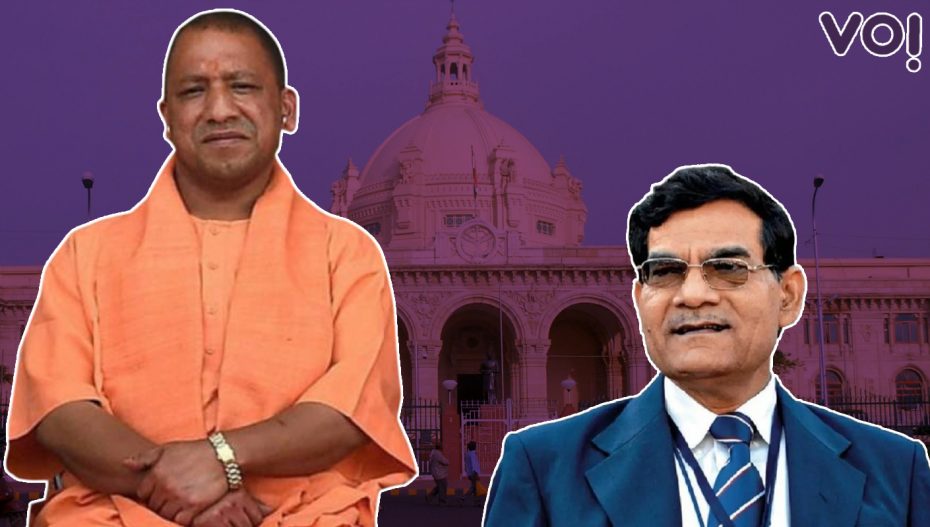

The first sign that Adityanath might wish to restore a degree of parity in the relationship was visible in the induction of Arvind Sharma in the new cabinet as a senior minister. A former Gujarat cadre IAS officer, Sharma holds the distinction of being the only Gujarat cadre IAS officer who was part and parcel of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s charmed circle of bureaucrats in Modi’s 20-year journey from Gandhinagar to Delhi. Sharma served in the chief minister’s office during Modi’s tenure from 2001 till the first half of 2014 and moved to the Prime Minister’s Office where his last placement was as an additional secretary.

Call it a reward or a career change, in January 2021, Sharma, whose ancestral home is in east Uttar Pradesh’s Khaja Kurd village, quit the civil services and opted for politics in his state of birth, an ideal crucible for an aspiring politician. He was elected to the legislative council as a BJP nominee. Sharma’s arrival set off the speculation that big times awaited him in Lucknow, possibly as a deputy chief minister in the Adityanath cabinet. The chief minister had resisted shuffling his ministerial council because he feared that Sharma could be a “troublemaker” as a Modi surrogate in UP in the run-up to the elections.

In his first term, Adityanath had two BJP deputies under him but the opinion was Keshav Prasad Maurya and Dinesh Sharma couldn’t “assert” themselves against the CM’s alleged “high-handedness” and “high jinks”. Moreover, Maurya and Sharma were short of backing from Delhi’s brass that might have given the heft to challenge Adityanath. The Delhi bosses acquiesced to Adityanath as they did not want to court trouble before the UP polls.

Sharma is expected to get a high profile infrastructure-related ministry.

As part of a balancing act, Maurya was re-inducted as a deputy chief minister although he lost his election from Sirathu. However, the norm of dumping losers was given the go-by the day Pushkar Singh Dhami was brought back as the Uttarakhand CM despite losing his seat from Khatima. It was apparent that Maurya’s return was inevitable. The “rationale” was he was the BJP’s “tallest” backward caste leader in the prevailing social scenario and the party could not displease the backward castes.

Adityanath’s second deputy, Dinesh Sharma was dropped to make way for another Brahmin, Brajesh Pathak. Pathak, a former Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) MP, was among the few ministers who was hands-on during the horrific second wave of Covid-19 in UP which claimed several lives.

Among the other notables who were dropped were Delhi’s favourites, Siddharth Nath Singh and Shrikant Sharma, although both won their seats. In Adityanath’s first term, Singh and Sharma were given weighty portfolios and appointed as government spokespersons until the CM re-jigged his media apparatuses and brought in his own spokespersons. Singh and Sharma were expected to be accommodated in the party organisation.

The ministerial council represented a mix of the old and the new. If veterans Surya Pratap Shahi and Suresh Khanna found a place in Adityanath 2:0, Jitin Prasada, a former Congressman and a Rahul Gandhi team-mate was the other notable induction. He combined experience, having served as a minister in the UPA government and briefly in Adityanath’s first government, with the expectation of being the BJP’s new “Brahmin” face with Brajesh Pathak.

The BJP’s allies, who rode back to power in the elections, were “rewarded”. Sanjay Nishad, the founder of the Nishad party and has a big following among the fisherfolk and boatmen communities whose votes count in central and eastern UP, and Ashish Patel, the husband of Anupriya Patel, who heads the Apna Dal (Sonelal) and is a central minister, were sworn in as cabinet ministers. Clearly, the BJP and Adityanath do not wish to rock the NDA boat before 2024.

The effort should be to hasten the pace of economic development and job creation. UP’s economy has grown at 2% annually for the last five years.