Restorative justice takes a humanistic approach of bringing about positive change in supposed offenders and addressing the root causes of crime-related behaviour, instead of the current retributive approach of imprisonment and punishment.

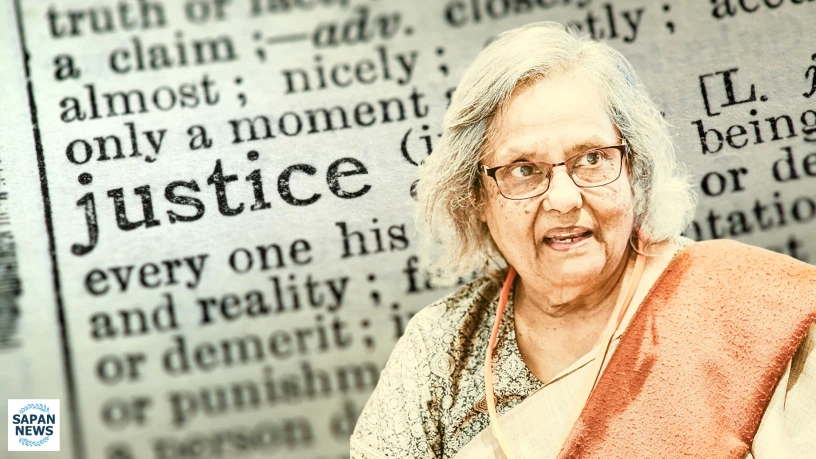

By Ela Gandhi

“Crime is a disease like any other malady and is a product of the prevalent social system,” wrote Mahatma Gandhi in 1946. In an independent, nonviolent India, he said, “there will be crime but no criminals. They will not be punished. Whether such an India will ever come into being is another question.”

Gandhiji’s main points are:

- Crime is like a disease that needs to be treated.

- Punishment does not prevent the spread of the disease.

- The overall socio-economic system causes the disease. Treating the individual can only be effective if we address underlying socio-economic issues.

Seventy-seven years later, the Covid-19 pandemic has taught us the significance of interconnectivity between human beings. If we could get a majority vaccinated and provide treatment to all, regardless of class, then why can we not make changes to reduce crime? Can we apply the same principles to crime as we did to the spread of the coronavirus?

Some tried to benefit from the situation by not sharing knowledge or the vaccines they developed. Still, international calls for equity and justice prevailed, indicating that restorative justice is possible if we put our minds to it.

The South African experience

My understanding of restorative justice is shaped by my experience living in South Africa, a country characterised by racial and ethnic inequality and numerous prejudices.

Incomes were allocated according to the racial divide, with the highest to the white population and the lowest to the African, and Indians and Coloureds in the middle. Access to facilities and living spaces was similarly divided based on race. There was a great deal of repression often manifested by torture and killings.

The Natives Land Act of 1913 pushed about three-quarters of the population, the African people, from the cities into remote reserves, comprising only 13% of the country’s land. Movement in and out of the reserves was restricted and controlled by the apartheid regime.

While some termed this segregation a protective measure, South African History Online describes these reserves as barren land unsuitable for agriculture, with African movement restricted into the urban areas by the notorious pass laws and other discriminatory laws.

Within this scenario after liberation, how was restorative justice to be administered? What are some of the key issues that plagued us at the time of the transfer of power and even today?

The first step towards change was to revise apartheid discriminatory laws and write a new democratic constitution where every human has fundamental human rights regardless of race, class, or gender. In addition, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was established to deal with past atrocities and divisions.

Truth and Reconciliation

Some of the statements made in South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission Report were:

- “… Those with the most power to abuse must carry the heaviest responsibility” [paragraph 80]

- “Having looked the beast of the past in the eye, having asked and received forgiveness and having made amends, let us shut the door on the past – not in order to forget it but in order not to allow it to imprison us …” [paragraph 91]

- “Restorative justice demands that the accountability of perpetrators be extended to making a contribution to the restoration of the well-being of their victims …” [paragraph 100].

- “… those who have benefited and are still benefiting from a range of unearned privileges under apartheid have a crucial role to play …” [paragraph 111].

A general sense of restorative justice for the oppressed people and the responsibility of the privileged to redress past injustices is evident from these statements.

South Africa has largely removed the segregation aspect of apartheid, but inequalities continue. The struggle now moves from race to class. Except for a few isolated cases, the responsibility placed on the privileged is yet to be realised. The rich of any race can access the best education, healthcare, and residences, while the poor continue to live in abject poverty and suffer due to poor education and healthcare.

A new system

The euphoria of 1994 had us frantically trying to address the injustices of the past. One way to achieve this was by carefully drafting the new Constitution, but it was daunting. The past was full of divisions, exclusions, and discriminatory practices. Many of us spoke about restorative justice, and we saw in a new system the idea of moving away from the punitive confrontationist adversarial system to a reformative system that would help people who violated the law get back to being law-abiding citizens.

Restorative justice is based on the idea of bringing about positive change in people who are offenders, correcting their behaviour rather than a system that punishes, imprisons, and sometimes even kills to remove supposed offenders from society.

Three essential parts of our Constitution were:

- To alter how the justice system office bearers are appointed (section 174, page 86)

- To look at greater community participation (section 180c, page 91) and accessibility of justice for all

- To change the punitive imprisonment system into a corrective one (section 34, 35, page 14)

On paper, these appeared to be lofty ideals and high expectations, but in reality, the system punished and humiliated those convicted of offences. Moreover, the community too wanted punishment for offenders. So, the vision of a well-functioning restorative justice needed to materialise. There are some examples of effective work, but the system needs to work better overall.

Racism and classism

At a recent community workshop, the community expressed frustration about poverty, unemployment, corruption, and poor service delivery. There was a need to guide the youth to access information and build a culture of responsibility. Growing trends towards racism and classism led to violence, especially in neighbourhoods with people of different races and classes. Many regarded individual criminal activities as being due to race and class; in reality, other race groups also suffered from crime by those of the same race, often caused by drug and alcohol consumption.

Many also felt there was an increase in gender-based violence. There was a clear need to empower women to leave an abusive relationship without fear. Also, a need to change the attitudes and way of reacting to perceived adversities of the perpetrators. Collusion between criminal activities and the police was seen as a significant problem. Participants cited examples of communities taking action to monitor court cases and police investigations to ensure justice.

They also expressed the need for strong and united civic structures. Communities shared some of the work in this direction; however, the work was fragmented, and there was a need for unity, coordination, and cohesion to strengthen the work. They highlighted:

- The need to make the electoral system and elected officials accountable.

- The lack of training and support for elected representatives

- The need to reform education and information dissemination

- Finally, the need to encourage more youth leaders with skills and knowledge

All these issues experienced by the community point to the need for a coordinated and well-thought-out restorative justice programme.

A compassionate approach

Some aspects of restorative justice are:

- Focus on the victim and the victim’s family who suffer indirectly due to their family member being victimised or killed

- Focus on the perpetrator as well. This should include causes of dysfunctional behaviour, including structural causes and familial problems

- If incarceration is involved, the role of the officers within the correctional services is also essential in making fundamental changes

- Restorative justice must address all these issues to attain success

At present, society and the officers in the correctional services see their role as ensuring that incarceration punishes the individual. They humiliate the person and force them to endure hardships so they do not repeat the offence. While the goal is noble, the means to it are not the most appropriate.

Recidivism continues. Instead of rehabilitation and personality transformation, a more hardened person emerges from incarceration. Over-population of the correctional centres, the people’s anger against crimes committed, and general thinking that those who commit crimes must be punished lead to a lack of empathy towards offenders.

There needs to be more basic education about human development, values, and humanism. There is an overbearing, self-centred attitude. Another factor is the pervasiveness of corruption in all sectors of society, including correctional services. Above all, we are doing little to address the causes of crime-related behaviour like inequality, poverty, violence to cure all ills, and lack of faith-based foundational training.

And so, the victims and their families, or the perpetrators’ families, receive scant attention. Punishment is the most important aspect of the sentence. No matter what religion we belong to, the justice system is geared towards rendering a punishment conducive to the offence committed. The harsher the sentence, the more satisfied the victim, the courts, and society.

Our scriptures reflect lofty ideas like “we are one human family,” “we are created in the image of God,” or “we are all children of one Supreme Being.” What is loudly expressed is vengeance against the offender and calls for “appropriate” punishment, even the death penalty.

This brings us to the crucial question of what constitutes an effective restorative justice model.

Universal wellbeing

I believe in a model where every person involved is brought together, and the process is designed to build:

- The wellbeing of all its members

- All notions of exclusion are challenged

- All parties experience a sense of belonging and allegiance to each other

- Promotes an atmosphere of trust among all its members

- Promotes a programme for the growth and development of each of the members

- Builds a society promoting equity, protection of human rights, and human dignity through mutual respect and equal opportunities

This is not a simple task, especially where victims and perpetrators are concerned, as their families are also brought in to work toward their mutual well-being. But it is achievable if there is willingness from all role players, including the government and those better endowed in our society.

Several methodologies were researched and tried during the Truth and Reconciliation process, and the quest continues today as we try to build a cohesive society.

South Africa can only achieve its global and redistributive development goals if it can implement institutionalised reconstructive community development, as educationists George Subotzky and Jan Currie warned in 2000. They criticised the excessive focus on the organisational and epistemological aspects of the “market” university, disregarding the essential role of higher education in reconstructive development.

The paper argues that the significant divide between higher educational institutions and society brings to light issues such as death, humiliation, denigration, racism, and knowledge exclusion. To address these challenges, the future social contract should consider collective forgetting and the importance of historical memory.

Paradigm shift

A key consideration includes using indigenous knowledge systems — a conscious paradigm shift from the Western models to accepting a diversity of knowledge to create a more appropriate model for those involved.

Understanding people is a crucial part of the restorative process. It is essential to consider their understanding of the issues, belief systems, and what is meaningful or not meaningful to them before implementing a programme.

Such knowledge unites diverse groups because it helps create an understanding of ‘the other’ and discard false notions. Traditional Western norms sometimes create hostilities and misunderstandings, which result in conflicts.

It is also essential that while cultural backgrounds determine the behavioural patterns of particular groups, religious backgrounds create a greater potential for people to be motivated to engage in actions leading to peaceful outcomes.

We have been discussing issues of repentance, forgiveness, restoration of dignity, and justice since 1999, when I organised a group on restorative justice at the Parliament of Religions gathering in Cape Town.

I learnt about this ancient tradition that dates back centuries. Indeed in our world today, we need more compassion, less arrogance, more justice, less vengeance, more restoration of dignity, and less condemnation and punishment.

People learn to think in different ways. Anyone who behaves in a particular way does so because they believe that is the way to behave. Those hurt by that behaviour must let the person know they are adversely affected by it. Such discussions lead to the transformation of both the insensitive belief system and the hurtful behaviour.

Only when perpetrators of violence understand and appreciate the injustice and inhumanity of their act of violence may they change and never repeat such offences.

The process could also help us transform our understanding and accept the other’s behaviour and belief system. This will help develop mutual respect, and we will find ways to live harmoniously together.

This may seem idealistic, but if individuals embrace restorative justice and actively work towards it, we have the potential to create positive transformations in our local communities. Such grassroots efforts can lead to broader societal changes, fostering peace and harmony.

Ela Gandhi is a social worker and political activist in South Africa, where she served two terms in the Parliament representing the African National Congress. She is the honorary Chairperson of the Gandhi Development Trust and Phoenix Settlement Trust and Co-President of Religions for Peace International. She is the granddaughter of Mahatma Gandhi. She received the Papal Madallion bestowed by His Holiness Pope Francis in February 2020. She wishes no vengeance upon those who murdered her son in 1993.

Ela Gandhi is the featured speaker at Southasia Peace Action Network’s June 25 virtual seminar ‘Restorative Justice, Truth and Reconciliation‘.

This story was first publish by Sapan News Network

Also Read: Underwater Noises Detected In Search For Missing Submersible Near Titanic