Bimal Roy’s 1959 film Sujata tugs at the heartstrings even today. More than 60 years later, this story of forbidden love between a high-class Brahmin man and a low-caste girl, Sujata, brought up in a Brahmin family, moves one to tears.

Sujata gets her name from the broad-minded engineer to whose house she is brought when just a baby. On the death of her labour-class, low-caste parents, Sujata, grows up with the engineer’s daughter, Rama, on an equal footing, unaware that she is not Rama’s biological sister. So, with all the innocence of her childhood, she hankers for everything that Rama is pampered with, be it books or birthday kheer, goodies she never receives because her adopted mother, Ammi, conditioned by social norms, makes subtle distinctions between the two girls.

Nevertheless, it is a happy childhood for Sujata. Since the engineer, Upendranath Chowdhury, is periodically transferred to different towns like Dehradun and Raniganj during his career, they have no interfering family or friends to raise questions about an achhut girl getting raised as a member of a Brahmin family. The years roll by, and Sujata blossoms into a responsible young lady, content to help with the everyday chores of the house while the fun-loving Rama prefers badminton and amateur poetry.

Bimal Roy’s depiction of the Chowdhury home is full of warmth, with Sujata being an intrinsic part of its well-oiled routine. Drawing up the shopping list for the cook in the morning, taking down the clothes from the terrace, bringing in the tea-tray at five for her Ammi and Bapu, tending to her plants at six, Sujata enjoys her role in the household. These scenes from everyday domesticity, with sounds of clock chimes and crickets, lend the film a comforting illusion of order.

Till Upendranath Chowdhury retires and settles down in the same city as Buaji, a close family friend. An orthodox old woman, Buaji strongly disapproves of Sujata, and shatters the calm order of the Chowdhury family, with her unapologetic practice of untouchability. Aggravating the situation further is her matchmaking of Rama with her grandson, Adhir, who is in love with Sujata, causing all hell to break loose.

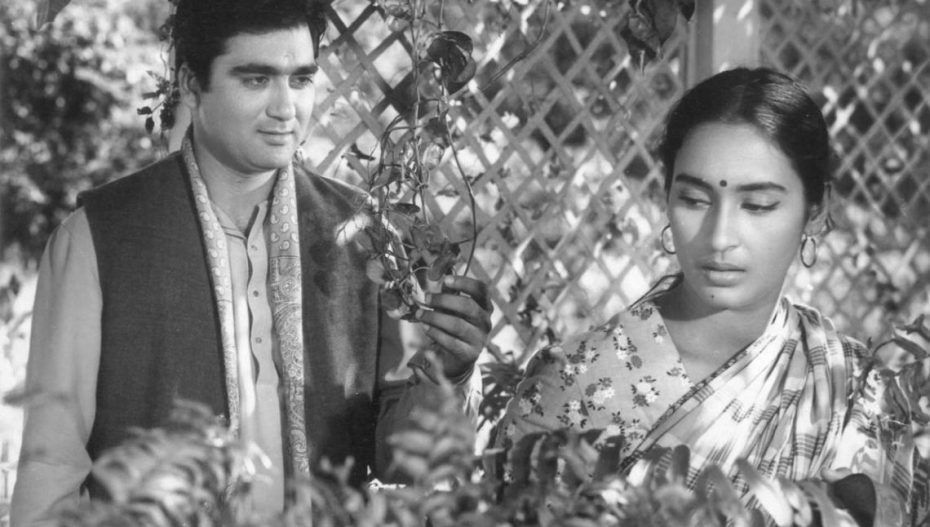

It would be a spoiler to narrate how the film unfolds hereafter. Some of the tropes may appear familiar, as over the last six decades they have been emulated in many films; but the pathetic fallacy of nature used by Roy to depict Sujata’s emotions is still very effective. When she is happy, cinematographer Kamal Bose captures the beauty of fluttering leaves, blossoming flowers and refreshing rain to reflect her mood. Played by actress Nutan, Sujata is like her plants, an unspoiled product of nature; and inspired by rain-laden clouds she sings her desires out aloud, with a Kaali ghata chhaye, Mora jiya tarsaye, a coming-of-age lyric by Majrooh Sultanpuri, put to lilting music by S.D. Burman.

The scholarly, supportive Adhir, who refuses to let Sujata’s caste come in the way of his love, is played by Sunil Dutt who matches Nutan’s understated style perfectly. When he croons Jalte hain jiske liye, teri aankhon ke diye, over the phone to Sujata, gently and adoringly, romance acquires a different level of sophistication all together.

The film has a meditative pace, interspersed with moments of liveliness (Shashikala as the carefree Rama, brings an endearing playfulness to the plot) and very hummable songs. So, though Roy raises pressing questions about the rigid caste system, never for a moment does he sound pedantic or preachy. It is in an emotionally stirring manner that he exposes its absurdities, and reveals how Gandhi’s concerted effort to do away with the caste system had borne little results in everyday life.

Sujata released in 1959; in 2021, we still haven’t rid the country of the obsolete practice of segregating people based on caste. Even as I type this, the morning paper reports a High Court ruling on the brutal killing of an inter-caste couple by the girl’s family in Mainpuri. Other headlines announce the nomination of backward caste politicians as cabinet ministers. Seven decades after Babasaheb Ambedkar and his team wrote a free India’s Constitution, political tokenism is all that our elected representatives offer as a solution to the cancer of an inhuman caste system. Sujata should perhaps be made mandatory viewing for those whom we choose to run the country. Emotions, rather than cold calculations of vote banks, might go a long way in doing away with the pernicious system, altogether. Permanently!

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article are that of the author. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of Vibes of India.