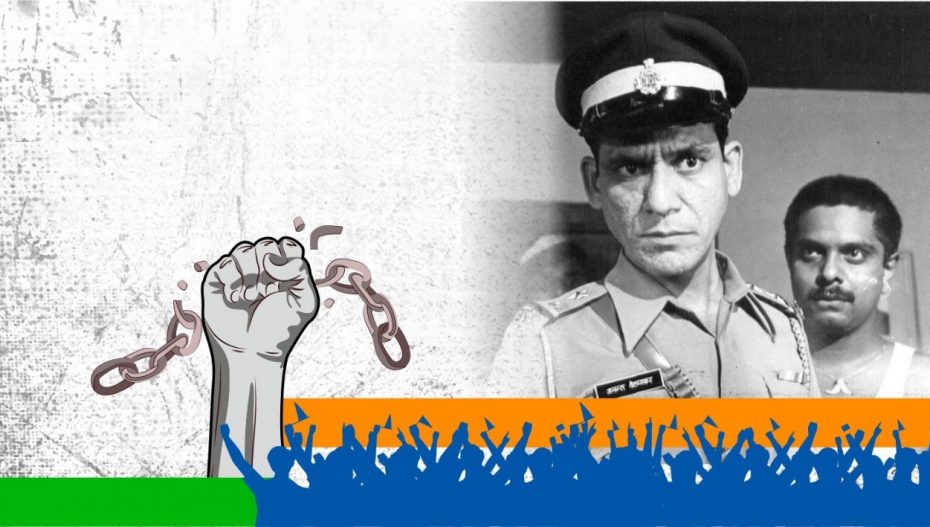

Om Puri as Sub-Inspector Ananth Velankar fought internal and external demons that were as relevant then as they are now.

In current times, when masters of half-truths rule the day, a gritty film from 1983, Ardh Satya, jolts you to the core with its stark revelations with almost every scene. Dark and sharply incisive, this Govind Nihalani-directed masterpiece is not for easy viewing. Watching Sub-Inspector Ananth Velankar getting inexorably trapped in a politician-police-underworld chakravyuh is agonising, to say the least, apart from being disturbingly reflective of present-day happenings.

Portrayed by a young, physically-fit Om Puri, SI Velankar is browbeaten by a cruel system. Bullied, first by his tough father played by Amrish Puri, to join the police force, he is later defeated by the strongly-entrenched culture of corruption that will not allow an honest, plain-speaking cop to survive.

In the early scenes of the film, you see Velankar, recently transferred to Gol Chowki police station, being invited to Rama Shetty’s den, a gambling-boozing joint, where a CBI officer is being entertained. “You have recently come to this police station, and I have heard a lot about you,” says Shetty, played by Sadashiv Amrapurkar, in a sickeningly sweet tone. “You arrested three of my men? That’s good,” he continues menacingly. Velankar leaves without saying much, smarting from within at this veiled threat.

The next morning, he finds Shetty’s men have been released on ‘orders from above’. Adding insult to injury, he is summoned by a senior inspector and severely reprimanded for challenging Rama Shetty’s power.

Back at the police station, he receives a complaint against hoodlums physically harassing women, and he releases his pent-up anger on them – beating them up black and blue. On the way home, he comes upon Pinto, an honest, drunken, suspended, police officer reduced to begging. Essayed by Naseeruddin Shah, Pinto is a depressing picture of what can happen to idealistic officers.

Intensely disturbed, Velankar asks Jyotsna Gokhale, a lecturer played by Smita Patil, out for tea. The two had clicked, earlier, at a party where both were misfits. At his tea date, he picks out a book of verse from the several she is carrying and reads out one which she has bookmarked. It is about being caught in a chakravyuh, about choosing between being impotent and being a man.

The balance scales are equally poised, being held up by an ardh satya. Battling inner demons, as he is, the Dilip Chitre poem sets Velankar thinking. Should he, unquestioningly, merge with the system or be man enough to confront it?

The dilemma troubles him at every turn of his duties at Gol Chowki. When his colleague, Hyder, informs him that a minister has asked for his suspension over the eve-teasing case, Velankar is, at first, defiant, “Let them suspend me. Let them conduct an enquiry. I will prove I have done no wrong.”

“You are too simple!” counters Hyder, played by Shafi Inamdar. “You have no idea how they will humiliate you. Look at what they reduced Pinto to. Do you know what they do during an inquiry? Khoon choos lete hain aadmi ka…”

The sympathetic Hyder persuades Velankar to cool down and meet a wheeler-dealer who has convenient contacts in Delhi. Velankar is saved from suspension, but he is not happy. Every time he compromises with the system, images of him being a mute witness, to his father’s violent outbursts against his mother, appear before him. The demons in his mind magnify. Unable to escape from the chakravyuh, he becomes alcohol-dependent, drinking even on duty. More so when he is forced to wield the stick on innocent people.

When Jyotsna witnesses his violence against striking factory labourers, sensitivity numbed by alcohol, she begs him to leave the police force. In the ensuing heated discussion, she tells him, “I cannot marry a man who is so ruthless.”

Defending himself, Velankar replies that biased newspaper reports have given her a distorted view of his profession. “Sometimes, we have to act tough to maintain law and order. Why don’t they report our good deeds? I have recently solved a bank robbery case and am expecting a medal on Republic Day. I would like you to be there when I get it.”

But the medal goes to an officer from the Crime Branch who had wanted Velankar to fudge reports during the bank case proceedings. Completely broken, Velankar gets drunk yet again and vents his frustration on an alleged petty thief during interrogation. “Saale, doosron ka haque choorata hain!!” he yells and thrashes the man so brutally that he dies in custody.

He is suspended and even Hyder does not want to help him. “Civil liberty groups are involved,” he explains. Lines from Chitre’s poem come to Velankar’s mind. You may get out of the chakravyuh, but the chakravyuh will continue to be there.

Indeed. The complex network of crime-police-politicians outlives those who protest against it. Decades after Nihalani turned an S D Panvalkar short story into a film, with Vijay Tendulkar writing the screenplay, scenes from the film re-play on our television screens, with one difference. These are real-life scenes, with many a Velankar succumbing to the pressures brought upon them by the Shettys and their political godfathers.

Pertinently, Tendulkar wove in a parallel track in the script about defenders of civil liberties, through Jyotsna. She is shown attending meetings on democracy where speakers like writer Shanta Gokhale point out the need for re-evaluating some of our venerable institutions, one of them being the police force. “People dying or being raped in police custody is unforgivable,” argues the writer, while strongly condemning the erosion of democratic institutions.

While Ardh Satya was made post- Emergency that brought many activists to the fore, the crying need for citizens to raise their voices against bureaucratic-political excesses continues even today. When officers of the Narcotics Control Bureau act like a law unto themselves, when politicians’ sons speed over peaceful protestors, when students languish in jail for months on end, not proved guilty of any crime, when the freedom of art is threatened, democracy is in grave danger. And a film like Ardh Satya is essential re-viewing.

This one cuts deep. We may choose not to acknowledge it, but the truth is there, gnawing at our conscience. As Alpana Chowdhury suggests, a classic is something which never loses its immediacy.