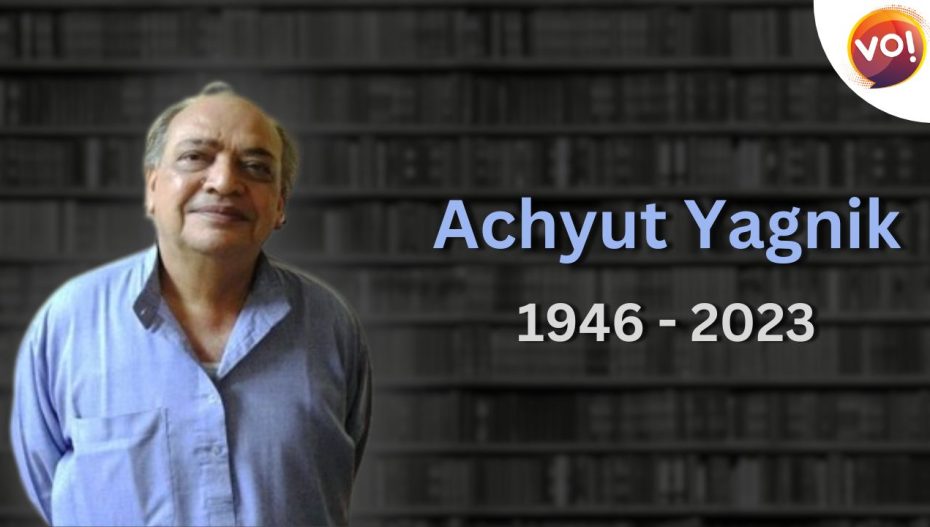

The present AI generation gains knowledge from digital sources through search engines, and our generation (those of the 1960s) relied on encyclopaedia and books by visiting the library frequently. For me, post 1985, my ready reckoner, my physical library in a human form was Achyutbhai. Such an encyclopaedic personality!

Today, those who gain the spotlight are mostly celebrities and politicians (for good or worse). Further, very few respond to the social and political crisis in the country, and often it’s in silos.

Public intellectuals were engaged actively in poverty alleviation and land reforms from the 1950s. They immersed themselves in Civil Liberties and Democratic Rights in the post-Emergency phase and responded to greater challenges of development (displacement, migration, labour, equality among class, caste and gender, and equity in the right to natural resources) in the 1980s and 90s, ensuring larger good in India rather than engaging with the electoral politics and political ruling.

A public figure was expected, as Gandhiji suggested, to think of ‘chhevadano manas’ [last person in the hierarchy] in a nation’s development policy, planning, and implementation. That defined, Achyutbhai, a public intellectual to me, articulating civilisational, political, and social justice perspectives, and bringing contemporary issues to the fore through succinct writings and discussions.

In 1985, Achyutbhai was introduced to us as a visiting faculty of Development Communication, a newly started post-graduate course by Gujarat University. In the first lecture, he bowled all of us: 10 students learning ‘development’ and ‘communication’.

We realised that our horizons of ‘mass media and communication’ and ‘growth-oriented development concept were kup madukta (a perspective of a frog living in a small well considers it as a world vision).

He widened our horizons of development communication in his vocabulary of knowledge and social action, and their cyclic, symbiotic linkages in only four lectures. I was very impressed by his encyclopaedic knowledge and descriptions of human endeavours, and I started interacting with him after lectures.

Achyutbhai had a habit of reflecting on contemporary issues from varied perspectives: civilisational history, social history, geopolitics, behaviour of certain caste-class, and decision-making by politicians (versus principles of polity) resulting in inequalities and injustices of varied nature. I decided to work with SETU: Centre for Social Knowledge & Action as a development communicator in 1986. SETU was formed in 1982 by Achyutbhai along with other public intellectuals and activists like Rajni Kothari, D L Sheth, Ghanshyam Shah, Anil Bhatt and others. As the name suggests, Achyutbhai undertook activities that created a bridge between social knowledge and action; he was already an established journalist, Civil Liberty, and Democratic Rights activist, having friends from different corners of the world.

After joining SETU, I looked forward to contributing to ‘development’ in a true sense with my communication skills and abilities, working with rural communities for their betterment. I was the first student of the Development Communication Course who joined an NGO with a humble salary, when the print and electronic media were more alluring and glamourised, and DECU and ISRO ran mass communication programmes which were considered mainstream media initiatives for development communication.

Until then, like any typical urbanite, upper middle class, educated person, I was not exposed to issues of poverty or poor people, women facing violence, social taboos and stigma, issues of food security, historical injustices to Adivasis and Dalits, and political decision-making and planning for dealing with issues of inequality and injustices.

SETU-PATRIKA, a magazine to communicate with grassroots workers was a brainchild of Achyutbhai (in his forties). I developed the Patrika further and sustained it for almost the next seven years with more than 15 issues. Patrika’s development-oriented content included new policies or legislation on land, labour, forest, water, migration, and so on. It offered different development initiatives and government schemes/programmes and their analyses: relevance, utility; experiences, views, and initiatives by grassroots workers in India.

I learned about two-way communication with grassroots workers, exposing them to the arena of policy and polity, and how to strategize for ensuring their rights, connecting local and global scenarios. I also developed low-cost, alternative media communication strategies with grassroots workers; all those communication strategies and initiatives were very useful in mass awareness raising and mobilisation and micro-level social actions and movements. Had Achyutbhai not developed this Patrika, which was instrumental in bringing about development issues and initiatives to the fore, the grassroots workers would not have learned how natural resource rights (rights over water, forest, and land) are integral to the empowerment of the communities that have remained on margins in Gujarat.

I developed networking skills, bringing various social and research institutions, activists, community leaders, and media persons together for opinion-building, lobbying, and ground-up advocacy for shaping up or amending a public policy.

Achyutbhai, like a typical journalist, used to read at least 10 newspapers until his last breath. One day in late 1987, he was discussing one of the headlines of Gujarati newspapers, ‘3 women do agnisnan in Gujarat every day’ and he said that is an indicator of violent Gujarati society, not only communal but also showing patriarchal traits. I was a bit perplexed with his statement, the way he linked an individual action with a generalised statement mentioning violence in Gujarati society, challenging the idea of ‘Gandhi’s peaceful Gujarat’. I decided to investigate and came up with an idea for a research project.

Achyutbhai never waited for funding for any social and development initiatives. We collected 1,200 news reports from four dailies over a year (1988) and later analysed them. This research exposed me to the ground reality of violence against women (and structural violence), challenges faced by police and law enforcement agencies, limitations of women-centric legislation, and the role and importance of various other social institutions that have been dealing with domestic violence since the early 1930s in Gujarat and new global parlance of ‘violence against women’. The research-based publication ‘Gujaratma Striona Kamot’ [Unnatural Deaths of Women in Gujarat] saw two editions, each with 1,000 copies, and was used by Gujarat police and the Gender Resource Centre, Gujarat State as resource material.

Had Achyutbhai not linked micro-mezzo-macro level engagements on such social matters, I might have overlooked this worthy issue. This helped me in writing my first research paper which I presented at an international conference and was published by an international Publishing House in the early 1990s. Since then, research-based publications and their versatile application remained one of my interest areas, which resulted in 15 publications and several articles/book chapters in academic publications.

After the book Unnatural Deaths of Women in Gujarat was published, I was offered a faculty position at two universities in 1990. I was simply contemplating it as a job that could give me social status and economic security. While discussing this offer, Achyutbhai shared his view on an established educational institution: its scope, ‘educational’ role, functioning, and contribution to society.

The discussion opened my eyes towards an individual’s association with a public institution of repute. His ability to portray a landscape that linked private with public and local with global was very discerning; such interactions shaped up a deeper understanding of ‘public domain’, ‘development’, and ‘social justice’.

Based on a discussion with him, I developed confidence that I need not chart a career path consciously as many of my peers do. He frequently talked about ‘swa-dharma’ and ‘aapad dharma’ for contribution to the society with thrust on social knowledge and action, saying that ‘you do what you like and you will find your ways to advance your thoughts and ideas’. I started imbibing such values. I could identify my interests in evolving communication strategies and strategic planning for just development, conducting research, teaching, and intervening in public affairs wherever possible in my late 20s.

I would like to share an incident which shows Achyutbhai’s integrity as a public intellectual, who never compromised on freedom of speech under religious or political pressures. Achyut Yagnik and Ghanshyam Shah (Director of Social Studies, Surat) edited an in-house academic journal of social studies, Surat. A historian wrote a research-based article on Swaminarayan Sect and mentioned that he was not a God. The Sect sued him along with two editors. Achyutbhai told me to keep all the documents in one folder, emphasising that, “I will never give up or kneel against such fanatic forces. I will fight the case if it goes on lifelong.” The author apologised and the legal suit was withdrawn.

The 80s were a watershed decade in the history of Gujarat, especially in the context of anti-reservations that were unjust for Dalits and Adivasis and the series of communal riots in 1981, 1985, 1987, and 1989. The debate on large dams and development-induced displacement and the need for R&R (Rehabilitation & Resettlement) measures, and the severe drought for four years (1985-89) brought about a change in land policies in Gujarat. All his future writings (in the 1990s, in the 21st century) are based on these concerns (books – Shaping of modern Gujarat, and Ahmedabad and several articles/book chapters in English and Gujarati). His very special contribution to me is a series of calendars published between 1995 and 2005: ‘Samanvay and Satatya’ [Synthesis and Continuity] covering how diverse communities have developed arts and crafts (shipbuilding, weaving), architecture, food habits and varieties, and habitation.

Achyutbhai kept sharing new ideas almost every day. We could work on some ideas and some are still unfinished agenda; publishing the intellectual biography of Prof. Rajni Kothari is one of them. I worked with SETU until 2000 but my association with Achyutbhai continued.

Achyubhai’s narratives, and his first-hand accounts of protests in Gujarat, have enlightened several of us about Gujarati society and challenges for social justice. His sharing on NavNirman Andolan (1973-74), anti-reservation agitations in 1981 and 1985, protest at Ferkuva by bringing up a human chain of one lakh people and preventing entry of Baba Amtte and Medha Patkar to Gujarat have helped me publish a monograph, Protest movements and citizen’s rights in Gujarat (1970-2010), at the Indian Institute of Advanced Study, Shimla. He was the first one to congratulate me when I was appointed professor at LBSNAA (the IAS training academy) at Mussoorie. My exposure to the politics of land and land policy regime was through Achyutbhai’s social activism.

Among his voluminous writings, some are very close to my heart. His booklet on ‘Lokpervi’ [Public Advocacy], the script of a documentary on ‘Rights of girl children, as a response against plentiful female foeticide in Gujarat in the early 1990s, communicate the symbiotic relationship between ecology and development (environment and sustainable development in today’s parlance).

His initiatives and advocacy strategies like ensuring the rights of the displaced population in Sardar Sarovar Dam against mining, and to prevent cement companies on the seacoast of Gujarat, transfer of Asiatic lions to Madhya Pradesh and rights of pastoralists in Gir forest, land policies – removal of restrictions of 8 km for buying land — are examples how a public intellectual represents social, ecological issues for sustainable development.

Chatting with Achyutbhai always revealed a new set of historical or socio-cultural information or development perspectives or ignited minds for exploring newer avenues. Travelling with him was a pleasure. It was fulfilling to access his treasure of knowledge on social history (Bhakti movement, Sufi movement), languages and their amalgamation in varied walks of life, temple architecture/ religious structures, ancient literature (Ved, Puran, Brahmans, and Upanishads), Dalit literature and use of metaphors (Lalit versus Dalit literature), art forms (impressionism, surrealism, abstract), and many more.

He had a huge circle of friends from different walks of life. Every visitor to him SETU has always benefitted from gifts which included loving interactions (easy access, adequate time spent, several cups of tea and tobacco smoking), information, and knowledge on varied subjects, relevant to public policy and social change. He used to tell me, “If you can think of 10 points on a topic, I have more than 20 points to offer in addition.” I vouch for this statement, his holistic thinking as a public intellectual.

As far as I remember, he never watched a movie in a theatre/cinema hall in the last four decades but he had updated information about every actor, director, and others. He never attended any Kavi Sammelan but read most literary works of old and new-generation poets. He could sing in a murmuring voice – poems/gazals of Faiz Ahmed Faiz, Sundaram, and others. His library is enriched with thousands of books, meeting his varied interests.

Achyutbhai is my Guru; he taught me how ‘personal is political’ with socio-cultural connotations, the importance of local-global connections and articulations, how and why individual freedom and dignity are supreme in democracy, and how they empower the individual/ community for ensuring human rights and social justice. I learned how different human endeavours (art, literary expressions, language) are integral parts of human existence and have survived through even dark ages in the world. My horizons have expanded and several newer horizons have come into my view over the last almost four decades.

Alvida Achyutbhai! We will live with some of your teachings and doings.

About the Author

Varsha Bhagat-Ganguly is a professor at the Institute of Law, Nirma University. She has authored research-based 15 books and more than 25 journal articles/book chapters on social and development issues.

Also Read: Soon, Your Face Will Be Your Boarding Pass