What would the Union Budget contain for farmers in the year following the historic farmer protests? This was a question on many minds as the Union Budget speech unfolded on February 1.

After all, the farmer agitation, which held the nation’s attention for more than a year, did not end but was merely suspended in December 2021. The suspension was based on written assurances given by the government on their key demands in addition to the repeal of the three farm laws.

The most important of these demands is the legal guarantee of Minimum Support Price (MSP), on which a committee was promised but has not materialised until now. The farmer organisations made it clear that if the assurances are not met, nationwide protests would be relaunched.

Considering this context, what did the Budget offer to farmers?

Strikingly, there was no attempt in the Budget either to address the immediate demands like MSP or to offer other solutions to the farmers’ underlying concerns about lack of remunerative prices, unfair markets and rising input costs. Neither did the Budget announce a major giveaway to farmers to shift the conversation as many had speculated – such as an increase in PM-KISAN benefit from Rs 6,000 per family to Rs 10,000.

Instead, the share of Agriculture and Allied Activities in the total Budget was reduced to 3.8%, whereas it was 4.3% in the Budget Estimate of 2021-22 and 3.9% in the Revised Estimate.

Many key allocations have been reduced and the fertilizer subsidy has seen a steep drop of 25% from the previous year’s revised estimate. The share of Rural Development in the total Budget fell to 5.2% compared to 5.5% in the previous year, underlined by a deep cut in the budget for the MGNREGS from last year’s revised estimate of Rs 98,000 crore to Rs 73,000 crore in this Budget.

Many farmer organisations have interpreted the Budget as the Centre’s act of vengeance against the farmers for their agitation. If that seems extreme, at the very least this Budget is telling the farmers and rural India, “We don’t give a damn what you want.” This at a time when even the corporate sector was telling the government that rural incomes need to be boosted because the low rural demand for goods is hitting the economy.

This year is notable as it was the goal for doubling farmers’ income which was promised six years ago in February 2016 and has been a staple item in all Budget speeches and the speeches of ruling party leaders including the Prime Minister.

Now, when we have reached 2022, the Budget speech did not even mention it, let alone give an account of the progress.

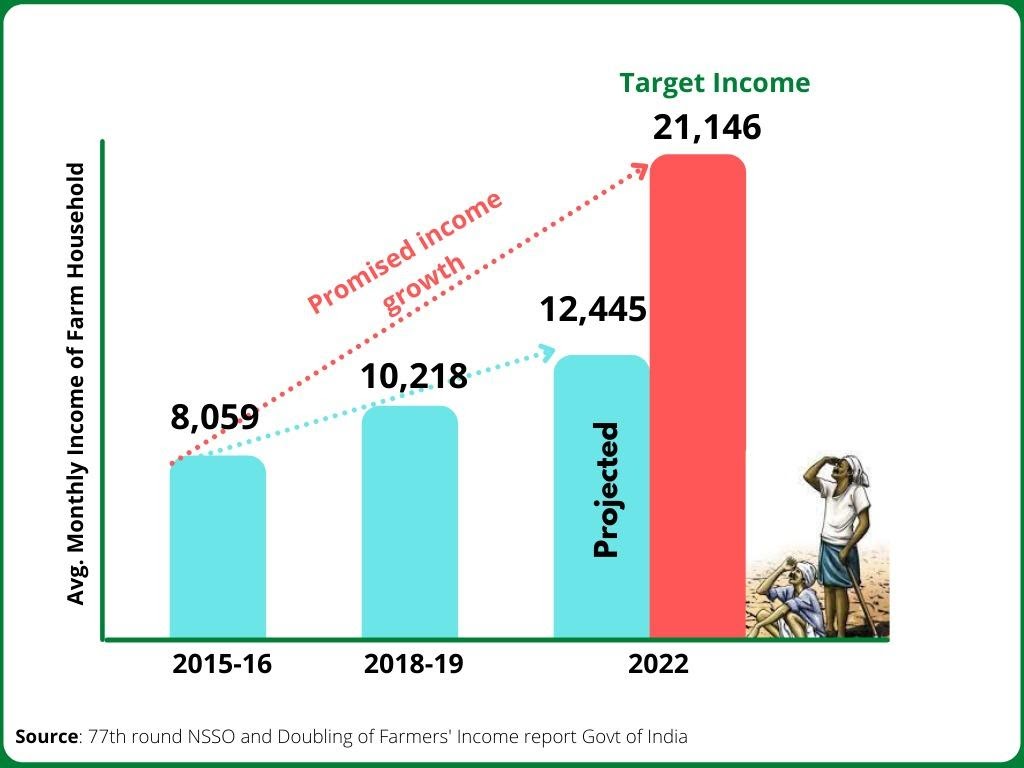

Here is a quick accounting that shows why the Union finance minister chose to stay silent. As per the government’s Doubling Farmers’ Income Committee report, the benchmark household income of 2015-16 was Rs 8,059 per month and this was promised to be doubled in real terms, taking inflation into account. As such, the target income by 2022 is Rs 21,146 per month.

At the mid-way point of the six years, the estimated monthly income of farm households in 2018-19 was Rs 10,218 per month in nominal terms, as shown by National Sample Survey Office’s (NSSO) 77th Round data released in 2021.

A projection for the next 3 years adjusting for the annual agricultural growth rates gives an estimated income of Rs 12,445 per month in 2022. The target of Rs.21,146 remains a mirage.

Doubling Farmers’ Income: Promise vs Reality

Note: Income for 2022 is projected to adjust for annual agricultural growth rates.

The finance minister began the section on agriculture proudly declaring that in the present year 2021-22, the procurement of paddy and wheat will reach 1,208 lakh metric tonnes benefiting 1.63 crore farmers with Rs.2.37 lakh crores indirect payment of MSP value. Such large figures are designed to catch budget day headlines even though the 2.37 lakh crore figure is not a budgetary allocation towards farmers, but simply the purchase value paid by procurement agencies to farmers in return for their grain.

But in reality, these figures exposed a reduction in procurement compared to the previous year, when the figures were 1,286 lakh metric tonnes from 1.97 crore farmers spending Rs 2.48 lakh crore.

It is more important to look beyond paddy and wheat procurement to examine the implementation of MSP. On the one hand, the Budget speech of 2018 by the then Union finance minister Arun Jaitley declared a commitment to ensure that all farmers can sell their crops at the declared MSP.

Since then, this government and PM Modi have repeated their verbal assurances on MSP. On the other hand, the government claims that bringing a legal guarantee for MSP is not practical. The best way for the government to make its case would have been to expand and strengthen the existing MSP schemes and show that it can ensure that the largest majority of farmers get the MSP in all the 23 crops under the support price regime, without requiring a lawyer.

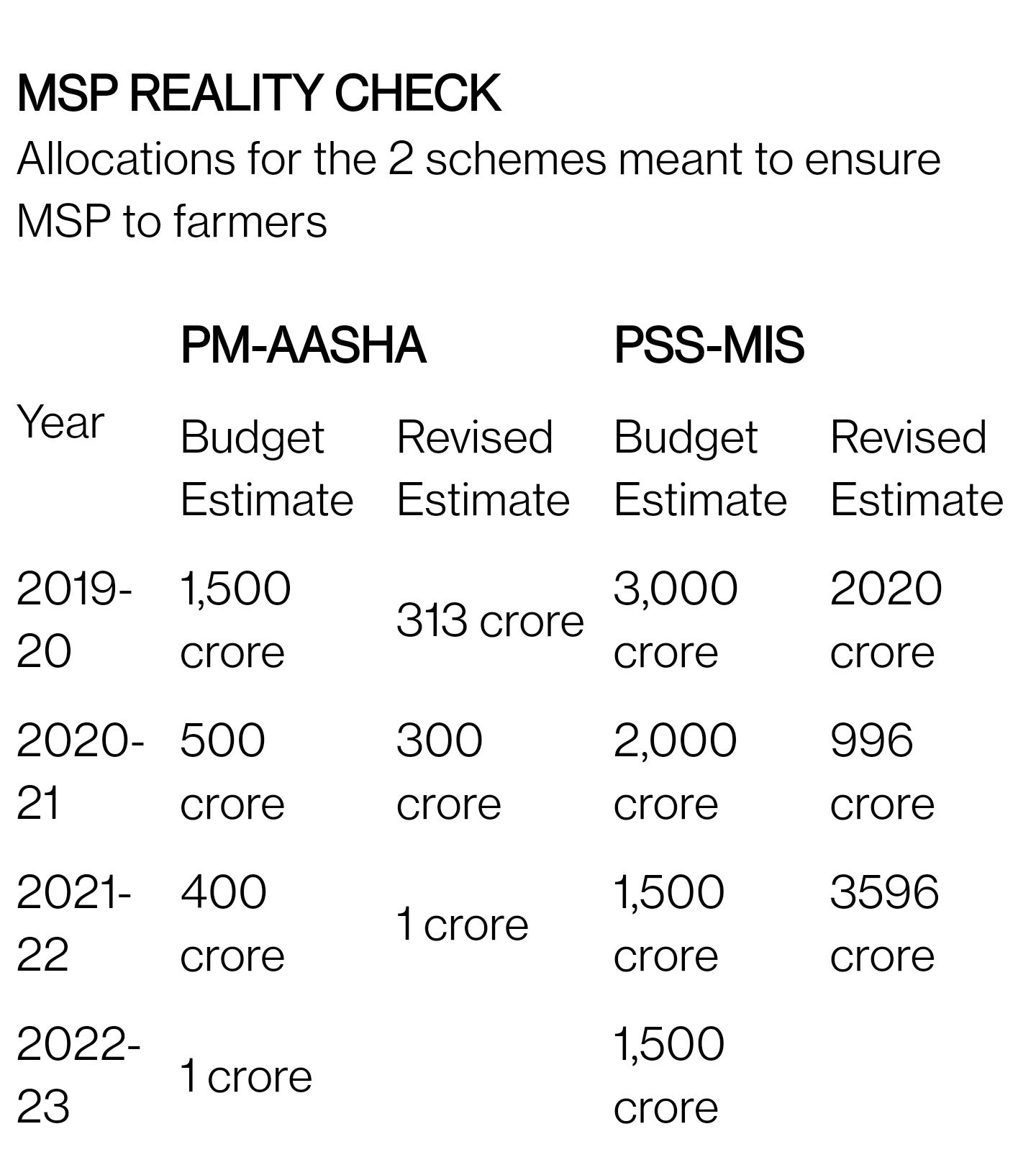

However, the PM-AASHA scheme (Pradhan Mantri Annadata Aay Sanrakshan Abhiyan), introduced in 2018 as the flagship scheme for implementing MSP, has turned into a hopeless ‘niraasha’ with its budget allocation dwindling from Rs.1500 crore in 2019-20 to Rs 1 crore in 2022-23.

Even the Price Support Scheme-Market Intervention Scheme (PSS-MIS), which implements Price Support and Market Intervention and saw a high of Rs 3,596 crore in 2021-22, is allocated only Rs 1,500 crore in 2022-23. These schemes fall far short of what is required because the annual shortfall between the declared MSP value of crops and the average market value received by farmers is more than Rs 50,000 crore. It is this utter lack of commitment to ensuring MSP that justifies and fuels the farmers’ demand for a legally guaranteed MSP.

Compare to Rs 50,000 crores: Estimated shortfall between declared MSP value of crops and average market value received by farmers as per 2017-18 data. Estimated to be higher now.

A close look at the figures shows the performance of many initiatives. The one lakh crore Agriculture Infrastructure Fund was announced in May 2020 as part of Atmanirbhar Bharat package. However, after nearly two years, only Rs 2,694 crores have been disbursed as loans and projects worth a total of Rs 6,700 crores sanctioned (source: Agri Infrastructure Fund website). This is dismal performance for a much-hyped package meant as a stimulus for an economy in crisis.

The Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana (PMFBY) allocation has been reduced marginally to Rs 15,500 crore, but more importantly the scheme is floundering as evident from the number of major states which have pulled out of it including the Pradhan Mantri’s home state of Gujarat. The much-heralded “10,000 Farmer Producer Organisations” scheme had a paltry allocation of Rs 700 crores last year and the revised estimate reduced it to Rs 250 crore.

The new emphasis on natural and organic farming is to be welcomed in view of the widespread degradation of soil, water and biodiversity, and the changing climate. However, a rational and evidence-based approach is required rather than a dogmatic one. The strange preference to focus on a 5-km corridor along the river Ganga in the first stage beats logic and may only serve to delay the promotion of natural farming in rain-fed regions that are more amenable.

Despite the rhetoric, the budget figures are not encouraging. The Paramparagat Krishi Vikas Yojna (PKVY) scheme which was meant to promote sustainable agriculture was allocated Rs 900 crore in the previous year but only Rs 200 crore are being spent. In the new Budget, PKVY as well as many other schemes have been subsumed under an expanded umbrella of Rashtriya Krishi Vikas Yojana (RKVY) with no clarity on allocation for different sub-schemes. The existing guidelines of RKVY give autonomy of planning to the state governments, and this will hopefully be continued.

More disconcertingly, the Budget speech also seeks to promote drones on a large scale for spraying pesticides and chemicals. The emphasis is on high-tech agriculture and digitisation as the way forward. The agri-digitisation process has already led to serious concerns about compromising the interests of farmers in favour of agri-business companies and digital platforms. With no data protection laws in place, and with land record digitisation already resulting in lakhs of small and marginal farmers getting dispossessed from lands, the push to accelerate digitisation and high tech services in public–private partnership mode is not in the interests of farmers.

The most important takeaway from this Budget is an utter lack of accountability. Flagship schemes are falling apart without finding a mention. A major goal post was set to be reached by 2022, and now there is complete silence about it.

Instead, a new goal post has been set up for 25 years hence. Once again, an unmistakable way of avoiding all accountability. Even as ‘Amrit Kaal’ is being used as an abracadabra to conjure up a distant future, farmers seem to have no place even in such a future vision.

-This story was first published by The Wire