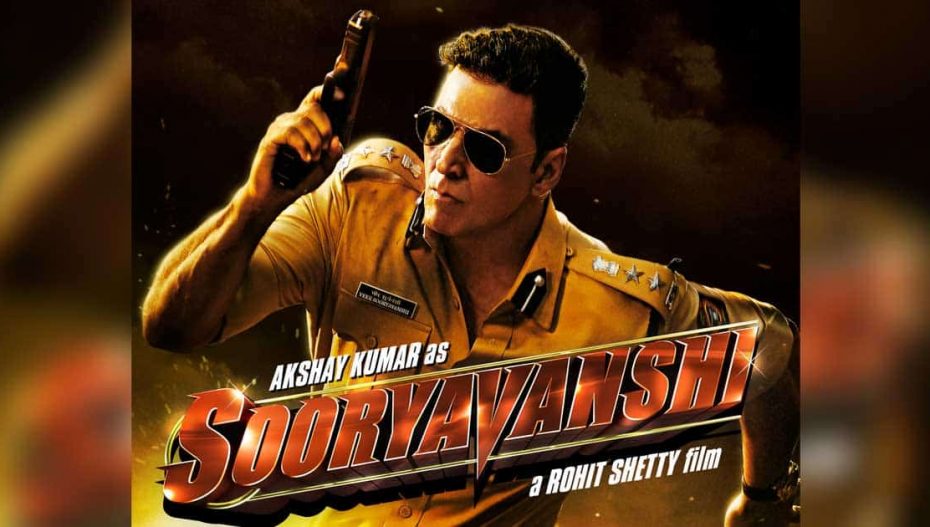

Akshay Kumar is a well-known Modi appeaser. Is filmmaker (sic) Rohit Shetty a Bhakt-in-disguise, as well?

With all its tumbling cars and ultra-HD action glitz, Sooryavanshi cannot really camouflage its constant preaching to (a majoritarian Hindu and thus aadarsh nagarik) choir, building its premise on a puerile black-and-white philosophy that is so last decade that it borders on the ridiculous. It is well-encapsulated in this dialogue: ‘Iss desh mein jitni nafrat Kasab ke liye hai, utni izzat Kalam ke liye (In India, there is as much hate for Ajmal Kasab as there is respect for the former president, the late APJ Abdul Kalam)’. In effect, Sooryavanshi repeatedly touts that a Muslim can either be Kasab or Kalam – there’s nothing in between.

With all Shetty’s posturing to present Sooryavanshi as part of the Singham-Simmba cop crossover universe, the film’s link with that world is only superficial, restricted to guest appearances by Ajay Devgn and Ranveer Singh. Sooryavanshi is more on the lines of Shetty’s first film, Zameen, released in 2003, when the previous NDA government was in power.

Zameen had a smaller canvas (and smaller budget). But its political message was no different from Sooryavanshi. Besides pushing a certain muscular nationalism, Zameen, like Sooryavanshi, focussed a great deal on themes like “the enemy within”, “sleeper cells that could be anyone around you”, and, of course, “who is a good Indian Muslim?”

The Binary of a Good and a bad Mussalman

In Zameen, the Good Muslim vs Bad Muslim narrative was pushed through a token Muslim character played by Pankaj Dheer, the captain of a hijacked Indian plane who lectures the hijackers on what ‘true Islam’ is. In Sooryavanshi, the lecture isn’t even offered by a Muslim character, but by Akshay Kumar’s DCP Veer Sooryavanshi, who tells the ‘Bad Muslim’ about the ‘Good Muslim’ in a number of scenes.

In one scene, his ‘Good Muslim’ is former colleague Naeem Khan (Rajendra Gupta), a retired policeman with over three decades of service and one who has just returned from Ajmer Sharif (a subtle sub-sectarian angle to what’s a good Muslim). In contrast to the clean-shaven former policeman with zero religious markers is the ‘Bad Muslim’ Kader Usmani, played by Gulshan Grover. Stereotypes abound: Usmani is shown as the topi-wearing cleric – with a long beard, shaved upper lip, prayer mark on his forehead. He’s depicted as running a charity foundation and holding sway in a Muslim ghetto. Let alone the real-life, everyday citizen Mussalman: how unimaginative can you get in fiction?

As for the late Kalam: recently, he was called a “Jihadi” by Hindu cleric Narsinghanand Saraswati, who went on to become the Mahamandaleshwar of the largest Akhara of Sadhus. If Kalam isn’t good enough as an Indian Muslim man, one wonders, who is?

Who are you to judge a prayer?

The fear-mongering could get actually dangerous when one steps over lines. A large number of Indian Muslims feel, say or do things in their daily life that have been associated with terrorists in the film – and some of these are markedly religious. The only Muslims shown offering namaz are the terrorists, the only ones engaging in religious acts – such as reading the Quran or having a tughra in their homes – are terrorists. The twin occasions where skullcap-wearing Muslims are portrayed as ‘good’ is when they are assisting the police or when they are helping their Hindu neighbours carry a Ganesha idol to safety – the only ways a visibly Muslim-looking person becomes non-threatening.

Ever since the rise of the Hindutva brigade, the regularity of attacks on minorities in India today is a well-documented, globally-acknowledged fact. Despite that, in Sooryavanshi, only terrorists speak out on the atrocities against Muslims in India, in the backdrop of the Dadri lynching in 2015, or as recently as October 2021, when people have been booked under the UAPA just for tweeting about the anti-Muslim violence in Tripura.

It doesn’t stop here. The “normal life” of a sleeper cell terrorist is depicted through a visit to the temple, while his “sinister or secret” life is shown immediately after that – of him offering namaz in private.

If this wasn’t enough, the climax has terrorists being thrashed with Hindu shlokas playing in the background. Puke-worthy, frankly.

Cinema in the Age of Islamophobia

Both Shetty’s Sooryavanshi and The Family Man (whose co-director happens to have co-written the screenplay of Zameen) are examples of filmmakers trying to reinforce fear-mongering while criminalising an everyday Mussalman.

It is probably too much to expect Bollywood to address Hindu majoritarianism, though some in the OTT universe have engaged with it in shows such as Sacred Games, Ghoul and Leila.

The safest pushback that filmmakers can give Islamophobia is to show ‘normal Muslims’ doing normal things. One of the nicest examples of this in recent times is two characters portrayed by Aparshakti Khurana – in Pati, Patni aur Woh and Luka Chuppi. As the protagonist’s best friend, his Muslim-ness is neither overstated nor denied completely.

In Luka Chuppi, he even says ‘Haan Musalmaan hun, doosre grah se nahi aaya (Yes, I’m a Muslim, I haven’t come from another planet)’.

In a hurry to make legal aliens of everyday citizens, maybe Rohit Shetty should stop and listen.