Naresh Parmar

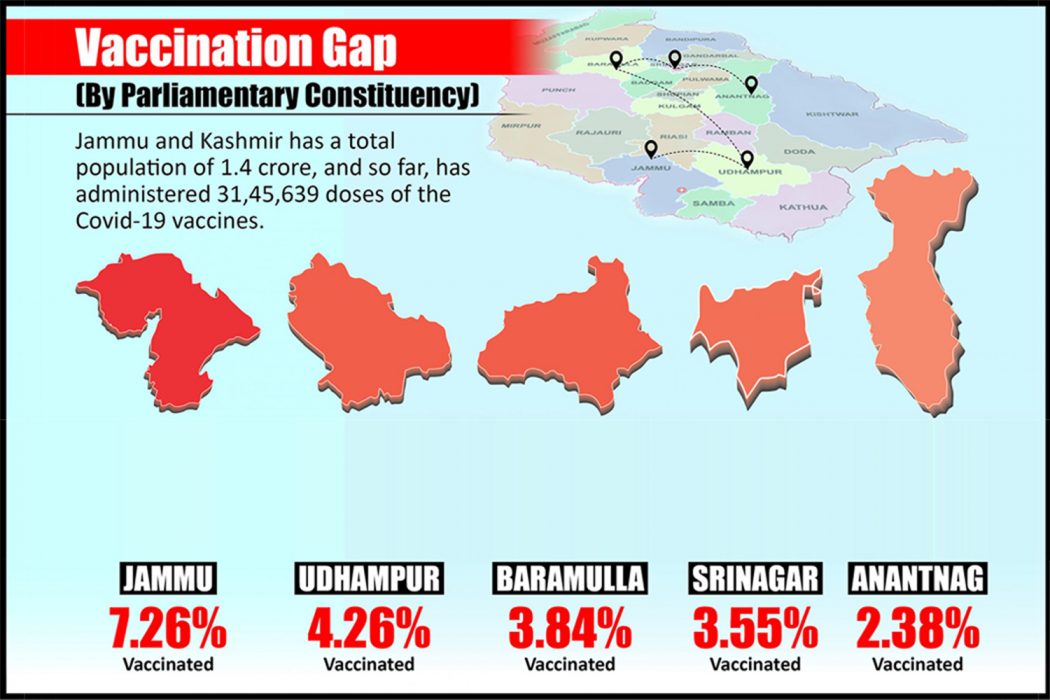

Jammu & Kashmir has one of the highest vaccination rates in the country due to its unique door-to-door vaccination policy. However, the distribution of vaccines remains disproportionate, with Jammu getting a much greater proportion of the vaccines.

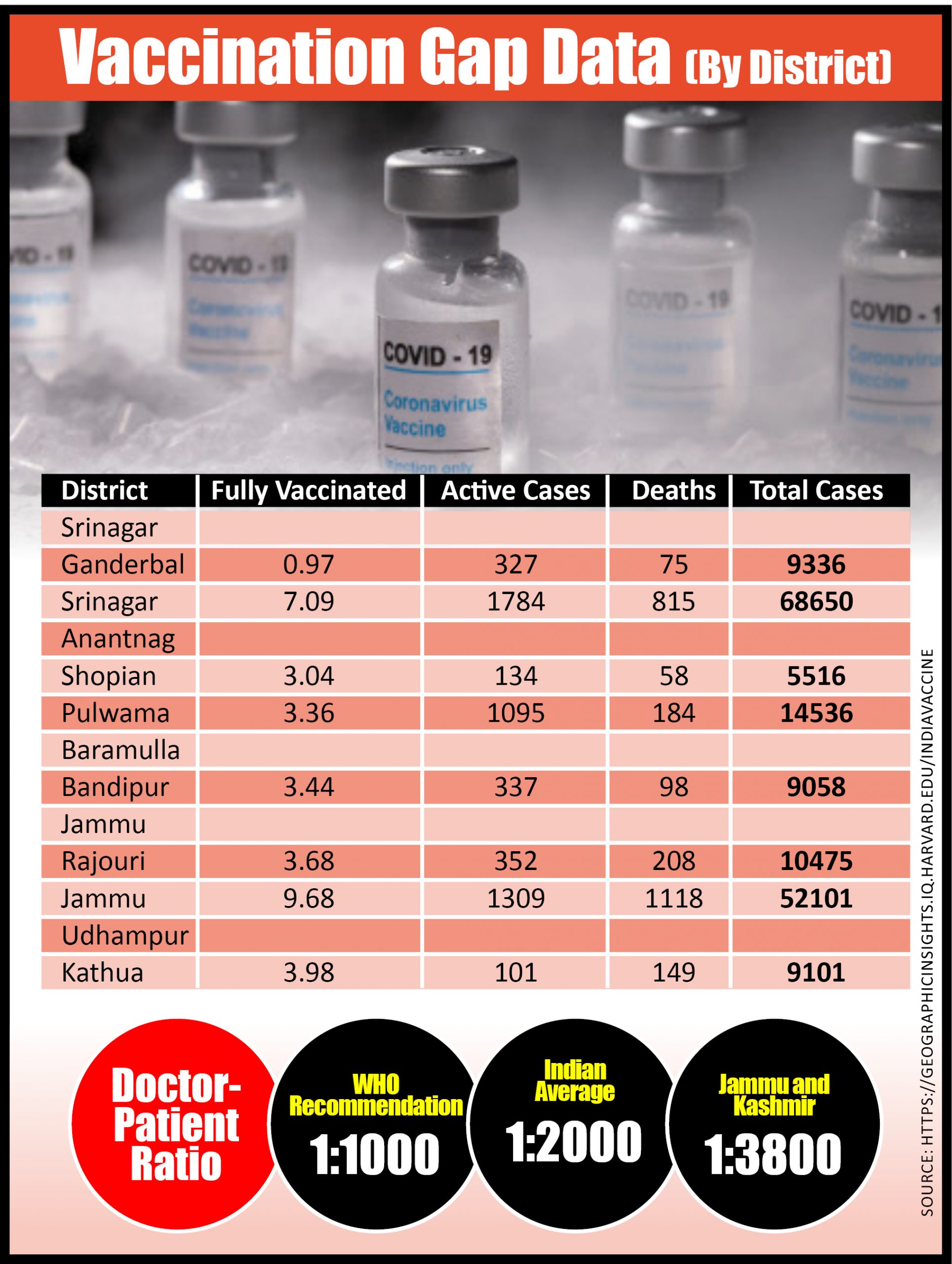

Srinagar has received less than half the doses as Jammu, finds the India COVID-19 Vaccine Tracker by the Harvard Center for Population and Development Studies that uses the government’s CoWin data. While nearly 10 percent of the population has been fully vaccinated in Jammu, less than 1 percent of Ganderbal’s population has had access to full vaccinations.

COVID-19 has further exposed and exacerbated the valley’s crumbling public health infrastructure. Since the outbreak, over 500 doctors and 860 paramedics have tested positive for COVID-19 in Kashmir alone, according to a recent report by Kashmirwalla. After an alarming surge of cases in the second wave, much of the union territory imposed strict COVID curbs. As cases start to decrease, some curbs have been relaxed this week, though the lockdown remains in force.

Even before the outbreak, a majority of Kashmir had already been under lockdown since India scrapped Article 370 from its constitution in 2019. The union territory’s limited health resources came under considerable strain with the pandemic and internet shutdowns in the region. Doctors had to struggle for hours to download even ICU guidelines as the Internet in the region was either off or limited to 2G early in the pandemic.

Crumbling Infrastructure of J&K

Unlike the rest of the country, nearly 97 percent of J&K’s healthcare needs are met by public healthcare institutions. These are far and few between. There are just six hospital beds available for every 10,000 patients in Kashmir. While 72 percent of rural areas and 79 percent of urban areas in India are dependent on private healthcare, the same has not developed in J&K due to its geographical remoteness and the region’s high militarization.

The lack of infrastructure is especially hard on the Gujjar and Bakerwal tribes, who must travel several kilometers to reach the nearest hospital, a feat close to impossible during the harsh winter months. These nomadic communities are the third-largest ethnic group in J&K, constituting 20 percent of its population.

According to the National Health Mission, only 50 percent of tribal people in Kashmir are able to visit public health institutions. Hospitals in the area remain highly understaffed. The doctor-patient ratio in J&Kis among the lowest in India. Compared to the country’s doctor-patient ratio of 1:2,000, J&K has one doctor for every 3,866 patients. The World Health Organization recommends 1 doctor for every thousand patients.

The state also suffers from a severe shortage of nursing staff. A 2018 audit of health systems finds that against a requirement of 3,193 Nurses as per the IPHS (Indian Public Health Standards) Norms, there are only 1290 sanctioned posts of Staff Nurses in J&K, with a deficit of 1,903 posts.

The 2018 audit also found that the existing manpower “is barely sufficient to run the health institutions in view of the sustained increase of patient flow across the state.” And this was before the pandemic.

A recent report by the Centre for Sustainable Employment at Azim Premji University (APU) on the impact of the pandemic revealed that 230 million additional individuals fell below the national minimum wage poverty line in the last year. Nearly 10.35 percent of J&K’s population lived below the poverty line before the pandemic. The economic cost of lockdowns and the pandemic and high hospital debts will push many further into poverty

The oxygen and hospital bed shortage in Kashmir was felt more acutely as the government imposed what many saw as an “oxygen gag” where the Srinagar administration directed oxygen manufacturing units to stop providing refills to private people and NGOs.

It has also imposed a media gag on doctors and healthcare officials, asking them to “desist” from speaking to reporters. The order warns healthcare workers that any criticism of “government efforts to control pandemic” in “uncalled for media reports” can lead to a prison term.