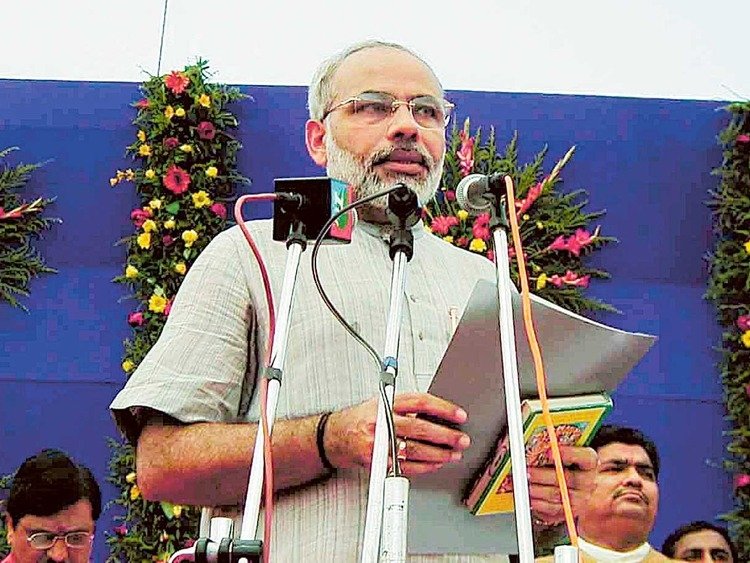

October 7, 2001, the day Narendra Modi took oath as the chief minister of Gujarat heading a beleaguered BJP, he famously declared: “I am here to play a one-day match.” He had the onerous task of turning around a party that was tottering within six years of forming its first full-fledged government in 1995, thus destroying to pieces the legend of a disciplined cadre-based party. And when a journalist asked him in his inaugural presser about his agenda, Modi cited a newspaper headline: “Rathyatra on Modi tyres”.

Twenty years on, Modi seems to be playing an unending test match playing the role of a bowler, the batsman and all three umpires himself. And this situation has not evolved over time — he is the same man he was on October 7, 2021, as he was on October 7, 2001. Only that he has grown into an invincible prime minister from an invincible chief minister. He has been charitable, at least once, in calling his style the Gujarat Model. It is, in reality, the Modi Model.

He created a situation in Gujarat such that if you remove him, the party collapses. It is Modi first and then BJP, in that order. Nationally, today, the scenario is no different. If he can suddenly remove the chief minister in Gujarat and his entire team without anyone questioning him, he could do so with his central cabinet too. If Gujarat saw three chief ministers between 2014 when Modi left for Delhi and September 2021, Uttarakhand got as many in less than 4 years.

Even a cursory glance at Modi’s politics and style of governance as chief minister in Gujarat holds the mirror to his prime ministership.

First the BJP. Right from 2002 in Gujarat through 2014 and 2019 national elections, Modi has brought the BJP to dizzy heights of unbridled power. He spoke of a Congress-mukt Bharat and the oldest party stood at an apologetic 44 seats after the 2019 Lok Sabha elections — a number that was not even adequate to give it a respectable Leader of Opposition post. In states where the BJP lost, power was snatched away. Where it saw the slightest threat even in places like Gujarat, dozens of legislators deserted the Congress to join the BJP.

He rode to power in Gujarat in 2002 on the back of a strident no-holds-barred communal campaign where “Miyan Musharraf” meant Muslims in general and “James Michael Lyngdoh (former chief election commissioner)” meant Christian minority — and therefore pro-Congress and pro-Muslim. The people and the media discovered JM Lyngdoh’s full name when Modi’s election campaign targetted him for he didn’t allow early election in the State.

On the one hand, his government was being accused of State-sponsered violence in the wake of the post-Godhra riots, and on the other, he ran the longest-ever election campaign that began in April until he romped home to power in December 2002. Invoking Gujarat’s pride in the face of his government under severe worldwide attack, Modi acquired a legend status of sorts. The people backed him and he developed an instant connect with their heart — like it or not.

He became larger than life — his experiment of changing CM Vijay Rupani and his entire Cabinet in September or earlier dropping senior and competent ministers like Ravi Shankar Prasad and Prakash Javadekar in his ministry’s reshuffle was first made when he was the chief minister. Modi had dropped all sitting municipal councillors in all six municipal corporations (subsequently eight) and single-handedly campaigned for the newcomers’ resounding victory. When he repeated rather dramatically at election rallies across various states in 2019, “aapka ek-ek vote Narendra Modi ke khatey mein jayega (your every vote will go in Modi’s kitty)”, it was time-tested in Gujarat.

Who next?

But there is a flip side. The personality cult he created has not only dwarfed the party but has also ensured that no second rung of leadership develops in the states. Gujarat, again, is the best example. The BJP’s first chief minister in Gujarat, Keshubhai Patel, who turned his most bitter rival after he had had Modi packing off from Gujarat in 1998, was almost politically finished when Modi took over from him in October 2001.

Patel’s subsequent attempt to form a separate party dominated by the Patidar community bit the bust in the 2007 elections. Patel’s Gujarat Parivartan Party later merged with the BJP with its most strident voice Gordhan Jhadaphia later becoming Prime Minister Modi’s backroom boy in Varanasi and Uttar Pradesh.

Jay Narayan Vyas, the man who was at the forefront of the legal and political battle against Medha Patkar’s Narmada Bachao Andolan and ensured the ambitious Sardar Sarovar Project saw the light of the day, was given an election ticket but his prospects were allegedly sabotaged from within. Today, Vyas is not even called to any important party meeting or involved in any decisions. Ashok Bhatt, a senior leader and a face of the party in walled city of Ahmedabad, was made a speaker of an assembly that meets only twice a year. And, of course, the late Haren Pandya who was denied a ticket in the December 2002 elections because he had refused to vacate his Ellis Bridge seat in Ahmedabad for Modi.

Today, Gujarat does not have a replacement for Modi with the chief ministers in his home state being easily called rubber stamps and none of them seem to mind it. Rupani, his then deputy Nitin Patel, still smarting after not being a chief minister despite his long experience, and all seniors who were dropped, can’t do anything but shrug. Rupani was dropped, though under him the BJP reported a sterling performance in the local body elections in February a year ahead of the 2022 assembly elections.

This is where Modi comes in. He understood right from day one that he and his governance was more a perception game than the nuts and bolts of running an effective state machinery. This is why within a year of his coming to power in 2002 came his high octane Vibrant Gujarat summits to demonstrate that against the image “created by the media and the Opposition parties”, Gujarat continues to be an ideal investment destination, and under him, with a modern outlook. Even scholarly leaders like Arun Shourie and journalists of all colours were enamoured of him. It didn’t take time before the Hindutva icon represented a visionary leader with a fresh development agenda. The brilliant rhetoric he created alternated — and still does — between Hindutva and vikas, to such an extent that they have come to sound like synonyms.