In Kailash Mukti Dham, one of the two crematoriums in Amreli town in Gujarat, four furnaces lie in different states of wreckage. The iron grille that holds bodies melted away in the fire from pyres that burned without a pause.

“Pyres were burning for 24 hours every day for a month,” said Maganbhai, a farmer who volunteers at the crematorium, winding back to the days when the second wave of COVID-19 in April and May 2021 devastated the town. Volunteers at the crematorium had to put up advertisements in local newspapers as their firewood supply ran out. Three members of the 20-odd team succumbed to the virus.

In the two months, 1,161 cremations were conducted in the two crematoriums. Since that was the maximum they could, the rest of the bodies were sent to neighbouring villages. And at the local Muslim graveyard, another 100 were buried; earthmovers were called in to dig graves because there were so many bodies.

The second wave of COVID-19 swept through every town in Gujarat, as it did across the rest of India. It left behind a trail of devastation and death. Despite the Gujarat high court’s order to publish accurate data, the state government claims –as of 10:49pm on August 16 – that 10,075 people had died due to COVID-19 since the pandemic began in early 2020. Prime Minister Narendra Modi has patted the Gujarat government on the back, saying it has “managed Covid crisis well.”

Now, evidence from official records proves that the state pulled a thick shroud over the death count and true magnitude of devastation.

The Reporters’ Collective got hold of copies of death registers from 68 of the 170 municipalities in the state. It is in these registers that a death and details of the dead are first recorded by officials. We collected copies of hand-filled registers between January 2019 and April 2021, running into thousands of pages.

An analysis of the death registers shows that in the 68 municipalities, 16,892 more people died from all causes between March 2020 and April 2021 compared to the same period the prior year – the year preceding the pandemic.

These 68 municipalities account for just 6% of the state’s population of 6.03 crore. By conservatively projecting the figure for Gujarat using simple proportionality, we estimate that the pandemic caused at least 2.81 lakh excess deaths in the state. That is more than 27 times the figure put out by the government as the official COVID-19 death toll in Gujarat.

Dr Caroline Buckee, professor of epidemiology at Harvard T.H.Chan School of Public Health, told The Reporters’ Collective, “The excess death counts from these municipalities suggest that the related official COVID-19 death counts are missing a large proportion of COVID-19 deaths.”

“Excess deaths” is the most accurate way to account for undercounting of deaths by officials. The ‘excess deaths’ are identified by comparing the total deaths in a particular period during the pandemic with the same period in a preceding normal year. Not all excess deaths can be linked to COVID-19. But, with no other reason to explain the surge in deaths, experts attribute most of these deaths to the pandemic and its fallout.

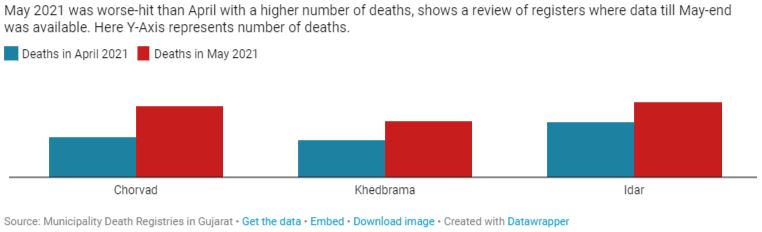

Gujarat’s excess death figure is conservative because the data from the municipalities does not include rural areas, which account for 57% of the total population that have minimal access to public health compared to urban areas. We have also excluded figures from May 2021, which even by the state’s account saw more deaths than April. This is because only three of the 68 municipalities had data till May-end.

In April 2021 alone, there were 10,238 excess deaths in the 6% of population under review, which is more than the official statewide COVID-19 death tally for the entire pandemic.

Gujarat Govt’s Lie Nailed: The Real Covid-19 Death Toll

By this measure, there were 1.71 lakh excess deaths projected in the state in April 2021 alone. And we are yet to know the numbers for May 2021, when the second wave peaked.

Deaths Spiked In May

The thousands of pages of death registers of these municipalities nail the official lie, district by district.

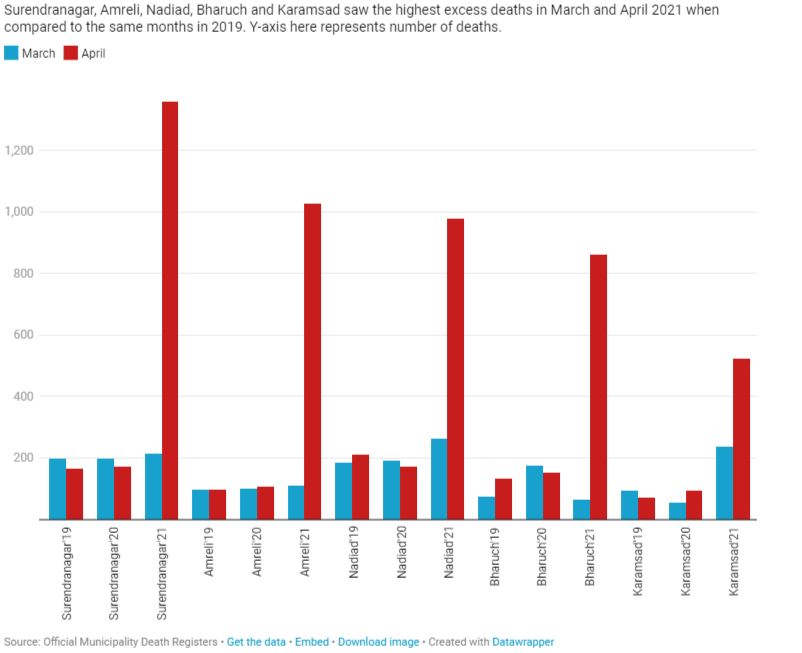

Take Surendranagar, a district in the Saurashtra region with a population of 17,56,268 according to 2011 Census data. According to the government, there were just 136 COVID-19 deaths in the district in total. But the death register shows that in one municipality, which holds around 14% of the district’s population, there were 1,210 excess deaths between March and April 2021.

Five Worst-Hit Municipalities

“Despite clear guidelines, it seems that the majority of COVID-19 deaths in India are going unrecorded. This appears to be for a mixture of reasons. In some cases, weak routine death surveillance is playing a part,” said Murad Banaji, a mathematician at Middlesex University, London, who has been closely following the pandemic.

“It seems the COVID-19 death recording guidelines are being wilfully ignored by some state governments. For example, death audit committees may be choosing to omit the deaths of COVID-19 patients with comorbidities from the official count. There have been reports to this effect from several states, including Gujarat,” said Banaji.

In India, the suppression of data for political reasons – along with incomplete death records and irregular classification of reasons for deaths in records – makes it impossible to count COVID-related deaths. In the absence of accurate government data on COVID-related deaths, experts globally recommend using ‘excess deaths’ as a proxy to understand the true level of devastation.

Apart from the deaths directly caused by COVID-19, many of the excess deaths could be the result of comorbidities worsened by infection or post-COVID complications such as blood clots, heart attacks and lung fibrosis.

“Official death counts after disasters rely on the attribution of the deaths to the disaster, on the death certificate,” said Dr Buckee.

“This system can be flawed. Deaths may not be attributed correctly to SARS-CoV-2, due to lack of diagnostic criteria in the early stages of the pandemic, lack of testing, political interference, and so on.”

“Pandemics are protracted public health emergencies – during which deaths occur not only from the disease causing the outbreak but eventually also from the impact of the pandemic on societal functioning,” explained Ayesha Mahmud, assistant professor in demography at the University of California, Berkeley.

“Excess mortality is, in fact, a much more reliable measure of the impact of the catastrophe than official data on cases and fatalities,” concluded Banaji.

To cross-check the estimates based on data from municipal-level death registers, The Reporters’ Collective secured the death records of one entire district, Botad, covering the urban municipalities as well as all the gram panchayats.

The government claims only 42 people died due to COVID-19 in Botad. But death records show there were 3,117 excess deaths in the district between March 2020-June 2021 – a whopping 74 times more than the government tally.

Counting the dead

Undercounting of covid deaths in Gujarat, like in several other states, was brought out by a vernacular media. At the peak of the second wave of the pandemic, reports of discrepancies in official death figures compared with crematorium data, though sporadic and anecdotal, served as an early warning of the government’s attempts at obfuscation.

Subsequently, the media also reported projections of excess deaths based on data from the Civic Registration System (CRS), in which birth and death records are eventually collated at the national level. The Union government countered it claiming the CRS takes time to be updated.

The Union health ministry said in a press release on August 4. “The CRS follows a process of data collection, cleaning, collating and publishing the numbers, which although is a long-drawn process, but it ensures no deaths are missed out. Because of the expanse and the amplitude of the activity, the numbers are usually published the next year.”

It is one of the reasons why The Reporters’ Collective spent three months meticulously gathering, translating and analysing the data from the primary source of death records – the death registers from which the CRS eventually draws data.

In Gujarat, according to the National Family Health Survey 2019-20, 93% of deaths were registered. The remaining 7% went unrecorded due to various reasons. Since people take some time to report a death in the family, the death registers record the date of death as well as the date of registration of death.

This data slowly drags its way up: from municipalities (in urban areas) and gram panchayats (for rural populations) to the district headquarters, where it is updated on the digitised CRS to give a state-level picture. But reconciliation and validation at the state, and further up, at the national level take time. This is the politically convenient excuse the Union government has used to suggest that independent analysis by experts of the excess deaths due to the pandemic should be put on hold.

A senior official working on demography in a Union government institution said, “While it might take up to two years for the CRS to reflect actual ground data at the national level, the municipality death registers are the best primary source to access till then to understand mortality rates without awaiting the finalised CRS data.”

Data transparency

The dataset from 68 municipalities of Gujarat is part of The Reporters’ Collective endeavour to collate and publish ‘excess death data’ from across the country. At the time of reporting, death records from more than 100 Gujarat municipalities and more than 35 districts in other states have been collated.

This data is being made publicly available under creative commons license on an online ‘Wall of Grief’, which is a collaborative effort between civil society, media organisations and interested individuals to collectively remember those who were lost to the pandemic.

The data from death registers of Gujarat’s municipalities was also shared with experts at the Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health, who previously investigated the true death count in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico.

“Mortality data are critical during and after a disaster – they provide important epidemiological information on who died, where, when and how, so that public health agencies can swing into action and sharpen their response,” said Dr Satchit Balsari, an emergency physician and expert in disaster response, at Harvard.

“Governments, around the world, make the mistake of trying to shield these data. But poor data only weakens public health response, when it is most needed.”

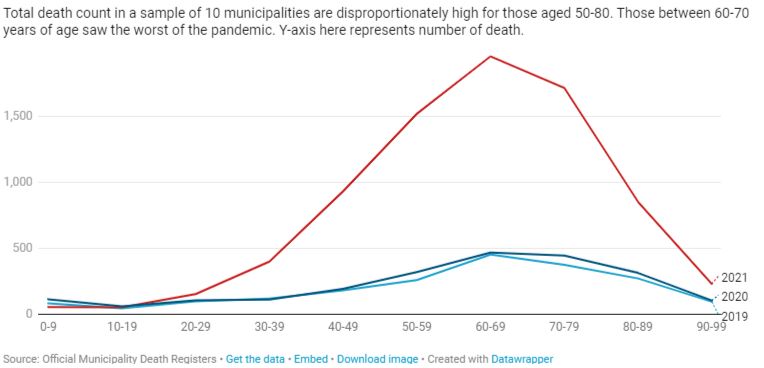

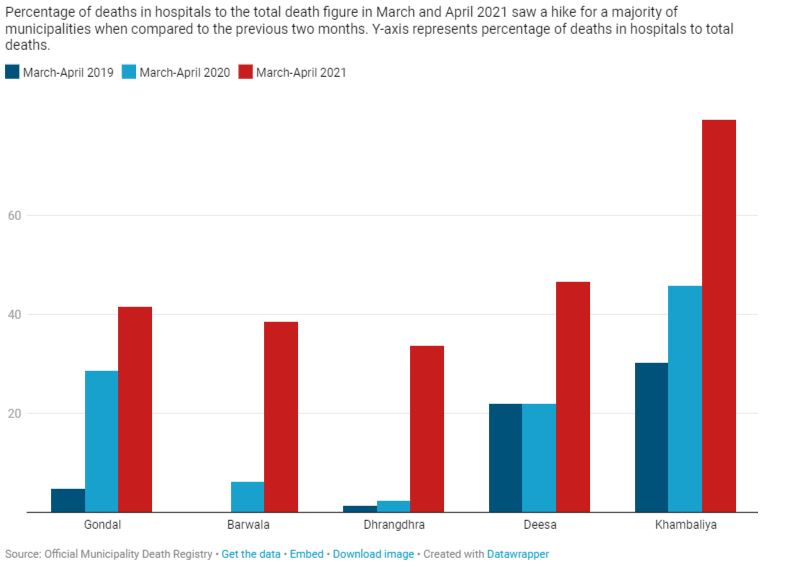

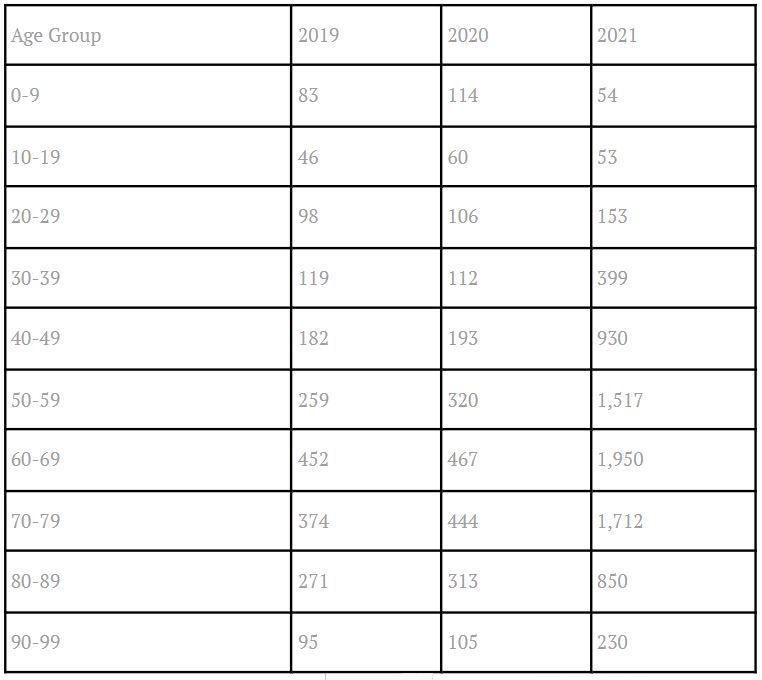

To understand the devastation ground up, one of the three reporters travelled through Gujarat in June. Data revealed by death registers was validated by testimonials of grief and loss. Data for a majority of the municipalities analysed shows that death among the elderly aged 50-80 recorded a steeper rise than in other age groups. The number of those who died at hospitals, against death at home, also surged during the second wave.

The Elderly Suffered Most

These findings mirror what happened on the ground.

“I have seen cases where oxygen supply was transferred from a 60-year-old to someone in their 20s,” said Saiyed Mehboob Rehman of Darul Ulum Mehboobiya, the association that oversees management of the graveyard in Amreli.

“Civil society groups led the efforts to arrange oxygen supply. There was no help from the government whatsoever. People were getting their oxygen refills in community halls that had no doctors around,” he said.

On April 19, 2021, Dr Bharat Pada, a radiologist in Amreli, stood in a crematorium clearing CT scan reports over email. In the pyre in front of him, his father’s body was being cremated. His 74-year-old father was diagnosed with COVID-19 seven days before death.

He was back in his sonography lab – one of only three in the town – the next day, to toil away in shifts that lasted over 15 hours a day and stretched well past midnight. “I turned a rock inside. I didn’t feel any emotions,” he told The Reporters’ Collective in his one-room clinic.

Dr Pada is among many who doubt the government’s COVID-19 fatality figures. “The daily official death toll would be the same number as the deaths of those I personally knew. It’s impossible that only that many people died.”

Death registers of six of the nine municipalities that form Amreli district show 1,257 excess deaths in April 2021, when compared to April 2019. But according to the government, there were only 14 COVID-19 deaths in the district, including in rural parts of Amreli, in April.

Share of Deaths in Hospitals Spiked Too

The excess death numbers collated from the death registers are likely to fall short of the actual deaths. People may take a day to a month to register a death in the family. But there is no reason to believe that the numbers in the registers exceed actual deaths.

The numbers

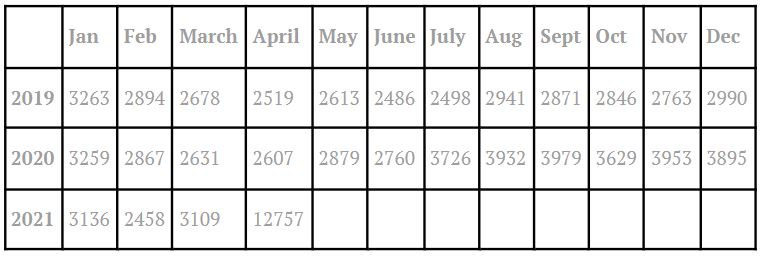

Graph 1:Mortality in early 2020 mirrored those in 2019, but the gap began widening from April onwards when COVID-19 began infecting people. The highest number of excess deaths across all 68 municipalities came in July, at 1,228. In 2021, deaths saw a massive spike in April in the midst of the second wave.

Graph 2: Official data and media reports make it clear that May 2021 was the worst of the nearly three-month-long second wave of COVID-19. However, for most of the municipalities, data was available only up until May 10. In the first ten days, May 2021 witnessed 3,532 deaths in 67 municipalities. The average of deaths per day for these municipalities in these ten days was around four times the figure for May 2019. Three municipalities where death data was available till May-end showed higher number of deaths compared to April 2021.

Graph 3:We analysed deaths across age groups for a sample of 10 municipalities over March-April in 2019, 2020 and 2021. Those between 50 and 80 years of age had disproportionately higher casualties compared to other groupings. People aged between 60 and 70 were the worst hit.

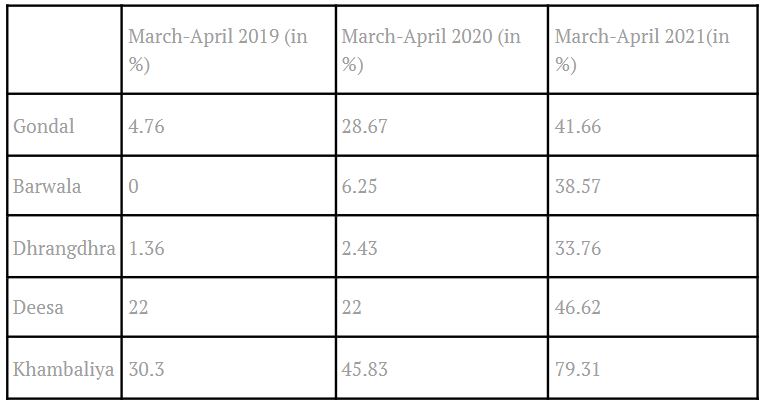

Graph 4: A pattern observed across a majority of municipalities analysed, where data was available, is that the percentage of deaths that took place in hospitals as compared to the total deaths for the area in March-May 2021 grew when compared to the same period in 2019 and 2020.

This article is written by Shreegireesh Jalihal, Tapasya & Nitin Sethi and was first published on The Wire.