Is it elitist to talk in terms of India and Bharat? Are Bharat and India merely two names and one nation or is the divide between the politically, economically and socially haves and have-nots more visible in practical terms?

Devdutt Pattanaik, one of my favourites, has often tried answering in his simple, yet scholarly fashion. The narrative of “India is English. Bharat is about regional languages. India is urban. Bharat is rural. English media caters to India. Regional media caters to Bharat. India values Western ideals. Bharat upholds traditional thoughts. India belongs to the rich and powerful. Bharat is of the poor simple folk,” is constantly endorsed by our political leaders often cutting across the party lines. For Pattanaik, the objective seems to create “heroes and villains.” But this, according to him, does not take them away from the need for India to learn from Bharat or Bharat to learn from India.

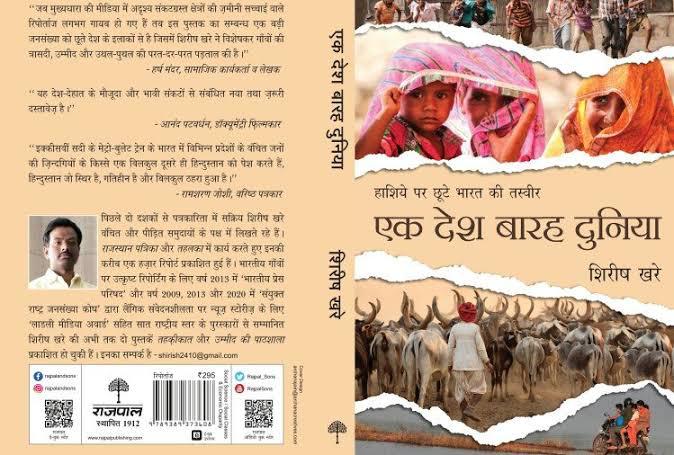

Journalist Shirish Khare’s “Ek Desh Barah Duniya” translated as ‘One Country Twelve worlds’ attempts to dwell and take a deep dive answer in these weighty, debatable issues with a zeal of a researcher, investigator, and as a passionate observer.

Khare’s book is an engaging repertoire born from his visits to these areas, which exposes the claims of development of the government machinery. In this book, that picture of India emerges, which neither becomes breaking news on TV nor does it find a place on the national page of any newspaper. Yes, such incidents are often forgotten after finding limited space in local newspapers.

The locations of Khare’s work are spread all over. He has travelled far and wide to observe and report on the lives of those living in parts of Maharashtra, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Telangana, Karnataka, Bundelkhand and in Thar and tribal areas of Rajasthan. In this way, he has tried to bring out the different worlds that exist within India, visiting not one or two, but during a decade of his long travels in these areas and spending considerable quality time with them.

As Khare writes in the foreword, “The physical barrier between our cities and remote villages have been rapidly eroding in the last few years, but the fact is that the space between the village and the poor has been shrinking equally fast in the general consciousness,” the notion that ‘India versus Bharat’ is similar to the British Raj’s divide and rule policy gets effectively dismantled.

Poverty in India is deceptive. Some may visualize the physical affluence in some of the Delhi slums, having a Dish Antenna, LED TV, and other facilities. Perhaps it has a lot to do with diverse par capita income and standard of living. The NSO’s CES data for 2017-18 showed that rural consumption between 2012 and 2018 had fallen by 8%, while urban consumption had risen by barely 2%. By 2019-20, poverty had increased significantly in both the rural and urban areas, but much more so in rural areas (from 25% to 30%). Any facts and figures of 2020-21 Covid 19 show a much more depressing picture of both urban and rural poor.

That’s where author Khare makes a pertinent point, “the place of the poor is shrinking in the general consciousness, then immediately the thought of some rich people also flashes in my mind, Man, these slums should be settled away from the city. They spoil the entire show of the society and then they also pose a security threat.”

Giving the reason for this ever-shrinking general consciousness, Khare writes, “When extremists are fuelling fear and hatred by targeting various forms of diversity, the man of the Gandhi, who is standing last in the queue will suffer the most.”

The first world of ‘Ek Desh Barah Duniya’ is Melghat of Maharashtra. Titled ‘He died yesterday, The author has exposed such a touching incident, which can shake every sensitive person.

“He died yesterday, did not even live for three months.” Hearing the news of the death of her innocent child in a flat tone from the mother, the writer is shaken to the core.

In Melghat, those days (the current situation is unknown) the death of children due to malnutrition was a common occurrence. The author writes about this at one place, “No one had any idea that the lush green hills, which had been described as one of the most beautiful places in the state by the Tourism Department of the Government of Maharashtra by showing a photo of a tiger, have mothers who were hungry to such an extent that they will just keep looking at their newborns who die starving.”

The incidents of the death of children stunned the author. For a moment the writer forgets who he is and where he is. Referring to this incident, Khare remarks, “I am to the north-west from Mumbai, the financial capital of the country, some seven hundred kilometres away… but brother, I am in which world!”

This Repertoire not only shows you the life crushed due to hunger, thirst or lack of facilities but also introduces you to the traditions and lifestyle of remote villages. The author takes you to the village of Makhla, craving water drop by drop, near the beautiful Bhimkund tourist spot in Maharashtra itself.

On the other hand, Jholemukka Dhandekar, a ninety-year-old in Bagalinga village, recounts tribal customs and traditions, “Everyone used to sit together once a year at Bhavai (a festival). The work of the whole year was divided; together they used to make laws. Yes, on the day of Bhavai, women also used to sit on an equal footing; they could marry second, third or even more times as per their wish.

Bagalinga is a village with a population of about eight hundred people, which is thirty-five kilometres away from the Tehsil, headquarter Chikhaldara on Melghat hill. In this village, you will get a glimpse of the simple, easy and prosperous lifestyle of the Korku community.

In his book, the author describes the agony of people suffering from displacement in this way-

“Those who weave life by adding straws

They scattered.

the village was broken and

were settled

Now age from expectation

And address from the shadow

Is pointless to ask.”

Through ‘Ek Desh Barah Duniya’ the author also takes us to Kamathipura, Mumbai’s largest flesh market in Asia. Where he introduces you to the inhumanity of ‘life in cage-like cells’ in narrow streets and also gives you interviews with the true stories of ‘Bela’ and other such girls, lured from Nepal.

“Why is there no light in the last cell of this cage-like cell?” When eight-year-old ‘Gomti’ answers this question, our sensitivity hides its face in the same dark cell.”

Shirish Khare takes us to Kanadi Budruk village of Maharashtra, in “Apne Desh Mein Pardesi” or ‘Alien in own Country’. The nomadic tribe Tirmali people live in this village. Tirmali people wander in various villages and cities carrying the idol of Mahadev Shankar on the Nandi bull and feed for themselves. This tribe has got no place in the social and justice system. Therefore, they have not been able to get the benefit of any scheme of the government.

While reading this book, you will be able to see the many worlds of India closely. There may be times when many similar scenes and episodes have passed through you, but you have not felt them. This book will give you the vision to feel these very lives.

Khare also takes us to many worlds settled in Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Chhattisgarh, Karnataka and Telangana and draws such a scene in the Narmada region-

A tired Gondni mother returned from work

breastfeeds her fourth child

Angels, Fairies and their Tales; Verses and Assurances

All are lies.

Oozing from the breasts,

blood tastes sweet,

The child is unaware of the obscene remarks of the contractor given along with ‘Thirty Rupees’ as the daily wage.

His smile in his sleep

on the sand of the river bank

spreads like moonlight.

The mother sitting on the land, watches and kisses wildly,

all her sorrows and dreams!

For me, Khare’s work has been both sad and refreshing. He has depicted a somewhat real picture of India or Bharat. I would say a must-read for all those who have a sense of belonging to this great nation.