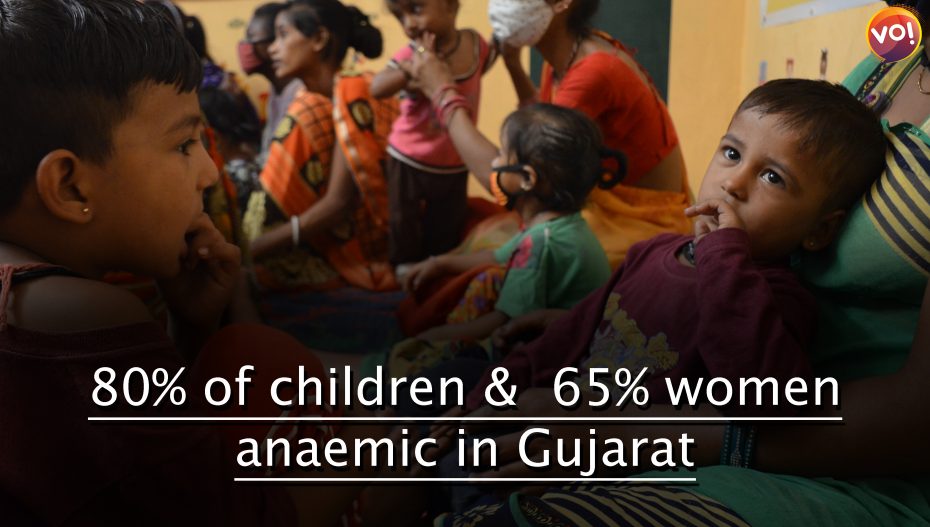

Even before the pandemic, four out of five children in Gujarat (79.7 percent) were suffering from anaemia – the highest in any Indian state – according to the latest National Family Health Survey – 5. Since then, the situation has only gotten worse.

“We didn’t have any money during the lockdown as there was no work. So, we borrowed and fed them what we could,” said Madhuben, a mother of two, living in EWS housing in Ahmedabad.

Many mothers in urban slums like Keshvaninagar, EWS and Ganeshnagar saw a fall in the birth weight of their children due to school and aanganwadi closures, as the pandemic stole lives and livelihoods. Early surveys show that nearly 80 per cent of families in these urban slums borrowed on average of Rs 16,000 during the lockdown.

“Severe malnutrition among children below 5 years increased by 16 per cent during the pandemic,” said Hetvi Shah, a public health expert and the project coordinator for Sneha Nutrition Centers that provide maternal health and child nutrition services in eight slums in Ahmedabad.

Anaemia among women in Gujarat is also among the highest in India. In 2019-20, nearly 65 per cent of Gujarat’s women were anaemic, the number saw a 10 per cent hike since 2015-16. This impacts not just the health and well being of women but increases their risk of maternal and neonatal adverse outcomes.

“In our fieldwork, we have met women who will feel the child is falling from their laps/arms but won’t have the strength to lift them. They are that weak,” said Pallavi Patel, Director at Chetna Foundation.

Nearly 46 per cent of the children and 30 percent of pregnant women in these urban slums were underweight when Shah and Chetna Foundation started working in the area. Things were starting to get better when the centre introduced programs like providing nutrition-rich food for severely undernourished children, cooking demonstrations for mothers and monitoring children’s weight as per their age. However, COVID-19 put a stop to many of the programs.

One major reason undernutrition remains high in urban slums is because of children and parent’s increased reliance on packaged foods they call “padikiyas,” according to Shah and Patel.

“Mothers feed these nutrition-less foods to children less than a year old because they are cheap, easily accessible and save time, particularly when the mothers are daily wage labourers,” she said. “Children also push for them cause the packaging is shiny and colourful and other children are having it. And, importantly, women lack the knowledge about good nutrition.”

While kirana stores with these padikiyas and tobacco are easy to find every few houses, the area houses only two Anganwadi centres. Madhu and Daryaben, both mothers in EWS, estimate that they spend Rs 50 daily for these food packets for their children.

398 out of 722 children in these three slums are not served by the government as aanganwadi centres cover only a limited number of people as per government rules.