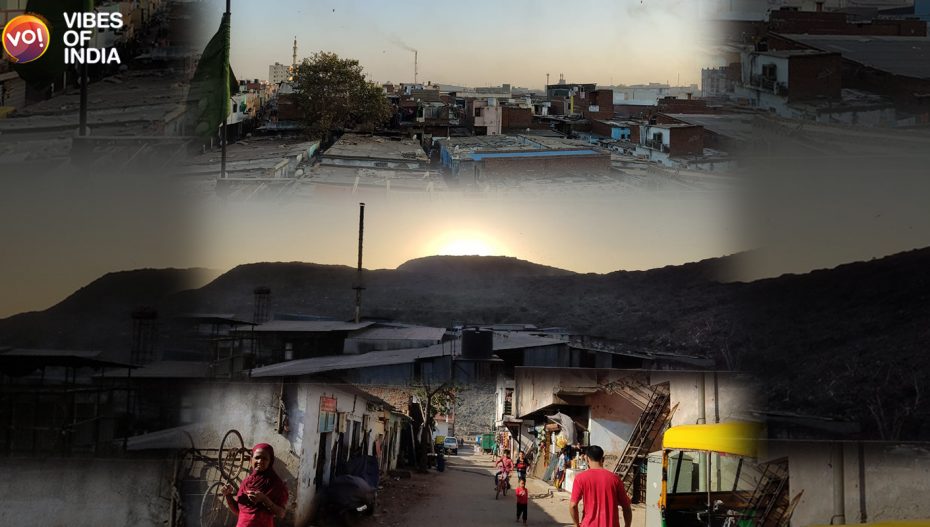

In Citizen Nagar, an urban slum in Ahmedabad, the Sun rises and sets in the 75-feet high Pirana garbage dumps. Sufiya Banu, 50 and her family resides next door to the Pirana. Around 50 families are residing in Citizen Nagar since they are internally displaced after the 2002 Gujarat Riots. Earlier, they were at Naroda, a mixed-neighbourhood where Hindus and Muslims lived cheek by jowl.

“Look at where we live now, you can see the garbage on all the sides, we breathe the toxic gas from the chemical and plastic factories around here. We are dying every moment, living a life without dreams for 20 years. 28 February 2002, our world changed suddenly,” said Sufiya, sadness zipping in her eyes.

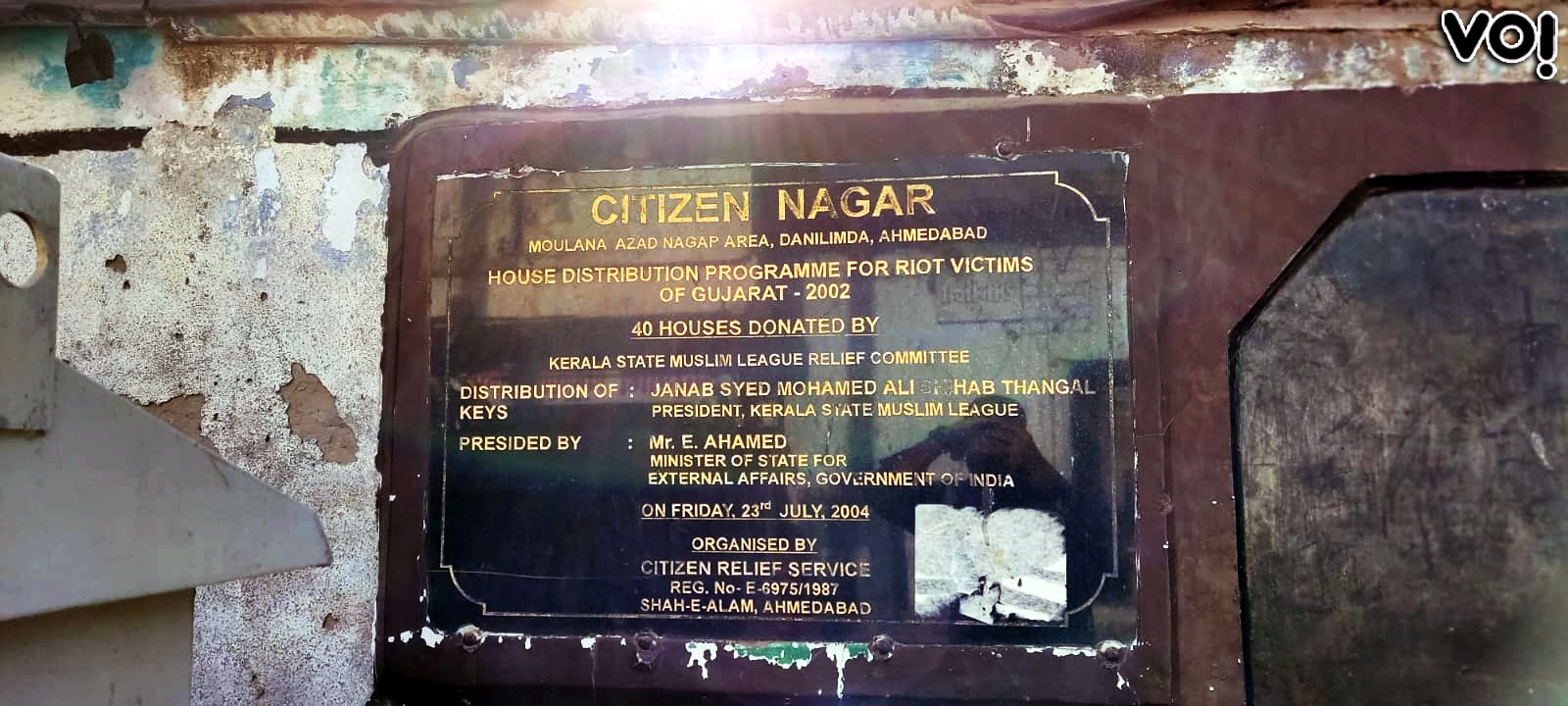

Citizen Nagar was set up as a temporary camp to give shelter to people, who fled their homes during the 2002 riots, but now it’s a big slum and government apathy is palpable. Many here say they have tried to find housing elsewhere in the city, but their Muslim names and lack of funds prevent them from moving out.

There are dumps of garbage everywhere, it emanates a foul odour and becomes the breeding ground for flies and mosquitoes which carry several diseases with them. Children were playing near the garbage dumps and in the dusty narrow street lanes. It’s oblivious of the fact that they are or may get infected with some fatal disease. The place stinks and anyone new there will suffocate. The houses are cramped and it’s difficult to even imagine the living conditions of the houses there unless and until you experience this nightmare. Six to twelve people share a cramped house with two rooms and only they know as to how so many people fit in such a small room.

There is no 24×7 water supply in the majority of the colonies. Residents of Citizen Nagar avail water from private tankers. “Every day we receive one tanker of water for the 150 plus families here, it never suffices our needs. Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation (AMC) doesn’t provide us with water. Even electricity is provided by Torrent power, a private one”, said Waheed Hussain.

Javed, 29, Sufiya Banu’s elder son recollects his memories, “The last thing I remember of my home at Naroda before we left was my Mumma (mother) was carrying me and my two brothers from our home. I saw fire everywhere, people running and shouting. The roads where I used to walk and run around was different from before. I saw a house burning down and someone was crying out loud, children are inside, please don’t burn them. Mumma was shocked and couldn’t stop crying. I and my brothers too started crying. To calm us down, Mumma told us they were bad people, who wants to kill us and we were to be strong and silent. As time passed, we got into the rooftop of someone’s house and hid there and I fainted. Two days later we were at a mosque, there were many.”

Currently, over 3,000 families are living in 83 relief colonies across Gujarat, 15 colonies in Ahmedabad, 17 in Anand, 13 in Sabarkantha, 11 in Panchmahal, 8 in Mehsana, 6 in Vadodara, 5 in Aravalli and 4 each in Bharuch and Kheda districts. Most of the colonies were built by Jamait-e-Ulema-e-Hind, Gujarat Sarvajanik Relief Committee, Islamic Relief Committee and United Economic Forum. The majority of the colonies like Citizen Nagar don’t have access to basic amenities and many residents are yet to have ownership rights despite living there for 20 years.

” It is still very difficult for us to understand, why the riots happened, our families have never hurt anyone. We had seen our family members, neighbours being killed and injured. We still grieve for the dear ones we lost. Look at where we live now, can you see any basic amenities, for 20 years we are living a life without dreams”, displaced Muslims told Vibes of India.

For the last 20 years, the Muslim residents of Citizen Nagar, Danilimda, Madaninagar, Millatnagar,… are constantly facing challenges from over-crowding, insanitary, unhealthy and dehumanising living conditions. They are subject to insecure land tenure, lack of access to basic minimum civic services such as safe drinking water, sanitation, storm drainage, solid waste management, internal and approach roads, street lighting, education and health care, and poor quality of shelter.

All these residents of various colonies are fitted well into the United Nations Guiding Principles on Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs), which say that IDPs are “persons or groups of persons who have been forced or obliged to flee or to leave their homes or places of habitual residence, in particular as a result of or to avoid the effects of armed conflict, situations of generalized violence, violations of human rights or natural or human-made disasters, and who have not crossed an internationally recognized state border.”

Though officially neither the Government of India nor the Gujarat government recognize IDPs as a category that needs special care and attention, many of them are still unwilling to live the deeply compromised lives they fear would form the condition on their return. Many IDPs want justice and have refused to withdraw legal cases against the perpetrators of violence. Then some refuse to return because they face a direct threat of violence. They have nothing left to return.

Vibes of India contacted the Lochan Sehra IAS, AMC Commissioner, enquiring about the situation of the residents in Citizen Nagar, he refrained from making any comment on it. Even the Behrampura ward councillors-Taslim Bhai Tirmizi, Kamlaben Chavda and Congress MLA Shailesh Parmar too refrained from commenting on the status quo of the displaced people living in Citizen Nagar.

Shehzad Khan Pathan, the Leader of the Opposition in Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation said that millions of rupees are embezzled in the name of Pirana dumpsite and citizens living in many areas are falling prey to a terrible epidemic rising from there.

“I along with the Congress corporators had submitted a requested appeal to the Municipal Corporation to urgently resolve the issue of Pirana landfill”, he added.

“Nobody cares for us, for politicians we just vote banks. At the time of elections they approach us for votes and will repeat it on the next election”, said the residents of Citizen Nagar.

“Most of these colonies have no basic amenities. There are no accessible internal roads, approach roads, gutter systems, street lights and inhabitants of the majority colonies are yet to have ownership rights despite living there for 20 years. The government should adopt a new rehabilitation policy for the victims of communal violence. It’s the only way to improve the basic infrastructure of these colonies”, Mujahid Nafees, an activist and convenor of Minority Coordination Committee, Gujarat, told Vibes of India.

Right to Education, still a privilege?

Javed, 29 and Jakir, 27 dropped out of school after the 2002 riots. Safiya Banu, their mother said, “We are extremely poor after riots, we lost everything. We weren’t able to continue the education of our two elder Son as we were afraid to send them to study too. Javed was in the seventh standard and Jakir in the fifth standard. The majority of the children at the age of 7-15 also dropped out of school during 2002-2006″.

“But we made sure our younger child, Jabari will complete school and college. He did it”, she added.

Jabari, a commerce graduate, said, ” Bhaiya you can see our situation here, it’s pathetic. For the last twenty-two years, I’m here. I was six months old when riots happened. All the older people like Mumma and Papa cry whenever they speak about riots. Their tears are enough for anyone to understand the pain. I studied seeing their pain, it was very difficult. Papa is a tailor, two of my brothers started doing daily wage jobs, with their income we moved on. There is no government school nearby, I had to travel 20km daily to finish school. Now also, the situation is the same and that’s the major reason why the majority of the children here too are now uneducated because they can’t easily access government schools.”

“There are other colonies like us where people don’t have access to basic amenities like drinking water, primary schools and hospitals. These were supposed to be temporary shelters for us. Getting a job is being very difficult, companies ask for experience and how will we have experience soon after Graduation. I had attended more than 30 interviews now, there is no response so far. Even after graduation, we can’t get a job”, he added.

There are only eight including Jabari, who has a bachelor’s degree in Citizen Nagar. Notably, there are no women who had college-level education. The majority of them are dropped out of school after 10th grade. This is the same situation in other colonies too.

Mariam is 16 and was in Class 9, during Covid she had dropped out of school as her father passed away. Now, she takes care of her mother, Asma Banu.

Mustakim, 20 returned to his home in Damilimda. He worked in Bengaluru as a waiter and he had come to a halt when the lockdown began. With that, his income of Rs. 10,000 – some of which she would send home every month – also stopped. He is also a school dropout.

In 2015, India adopted the UN’s 17 Sustainable Development Goals for 2030; the fourth of these is to “Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all.” The country’s Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Act, 2009, covers all children between 6 and 14 years. The National Curriculum Framework, 2005, emphasises the importance of inclusive classrooms, especially for students from marginalised sections and with disabilities. The central and state governments also offer several scholarships and incentive schemes to reduce the number of dropouts.

But the dropouts and uneducated are increasing in these displaced colonies. Dropping out from schools especially impacts girls – more and more of them either stay back at home or are married off.

For the children of Citizen Nagar, there is no government school in a 10km radius, there is a private school that charges very high fees. The socio-economic insecurities challenge their right to education.

Health is wealth, right?

Reshma appa has a grim expression while speaking from her house. She points at the Pirana garbage depot and said, “all the toxic waste from it has percolated into the groundwater. The water from the borewell is dirty and we can’t use it to drink and bath because it will kill us”. She is one of the witnesses of the riots.

The Citizen Nagar lies at the foothills of the infamous Pirana which is spread over 84 hectares and over 75 meters in height. The landfill has been Ahmedabad’s major dumping ground since 1982. Pirana is gauged to bear 85 lakh metric tons of garbage and is known for the toxic fumes it releases.

Citizen Nagar is located within the AMC’s limits but receives no municipal water supply. The people here relied on private tankers until a borewell was drilled in 2009. But the borewell’s water was never potable. A study done by the Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad, showed an extremely high content of salts, metals, chloride, sulphate and magnesium. At present, another borewell, drilled about six months ago, meets part of the colony’s need. But waterborne diseases and stomach infections continue to rage here. Women and children develop multiple skin diseases and fungal infections as a result of working with and consuming, contaminated water.

“We are constantly breathing toxic gases from the landfill and all the nearby plastic-chemical factories. Everyone here is suffering from lungs, kidney and liver ailments. Many had died because of this, they were never treated. How can we? What do we have? We have nothing”, Reshma appa told Vibes of India.

“Our colony is extensively covered by the media since 2002 with stories on the conditions of people living in houses they have no papers for, broken houses, lack of basic amenities and health, but there is no positive change happening to our lives”, she added.

There are no primary health centres in the 10-kilometre radius of Citizen Nagar and other colonies. “Patients from Citizen Nagar comes with a hacking cough and cold complaints,” says Dr Farhin Saiyad, who consults in the nearby Rahat Citizen Clinic run by charitable foundations and social activists for the community. “Breathing problems and lung infections are quite common in this area due to air pollution and hazardous gases afloat all the time. There are a huge number of tuberculosis patients in the colony as well,” says Saiyad. The clinic had to be shut down when the lockdown began.

“The threat coronavirus brought to the people of these colonies was extreme hunger and lack of access to medical help in the wake of a complete lockdown. In 15-20 days, we arranged relief kits and provided them to all the colonies where we were able to establish contacts,” said Manjula Pradeep, a human rights activist.

This area, with such appalling living conditions and hazards, was never given a primary health centre despite repeated requests for one. It was only in 2017 that the Rahat Citizen Clinic opened here, funded entirely through private donations and the efforts of people like Abrar Ali, a young professor of Ahmedabad University working on issues of health and education with the community. But it has not been easy to run the clinic. Ali has struggled to find the right doctors, willing donors and generous landlords. As a result, in two and half years the clinic has changed three locations and four doctors. And now even this clinic is closed due to the citywide lockdown.

Last but not least!

Housing and basic amenities remain the key concern among the residents of all colonies. In many colonies, the ownership of houses is yet to be transferred to them. This has raised the fear of being displaced for a second time. Besides, these colonies have not been provided with drinking water, approach roads, drainage, street lights etc.

They even stressed that the compensation given to them is inadequate. The government’s admission, the total damage to property during the violence came to Rs 687 crore, yet the total financial assistance for rehabilitation to the victims only came to Rs 121.85 crore. The state government returned Rs 19 crore to the Government of India, claiming that it could not make any use of it.

Notably, these relief camps are built on the outskirts of towns and cities across the state. These were meant to be temporary shelters but ended up being the permanent homes for those displaced in the riots. Many didn’t return to their old areas because of economic crisis and fear of volatile conditions.

Despite numerous complaints and protests, “Leaders have come and gone, making false promises”, says the displaced humans of Gujarat.

[Names are changed to protect their identities]

Pictures: Sayed Muhammed